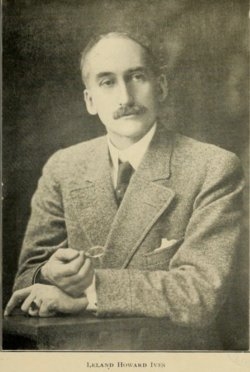

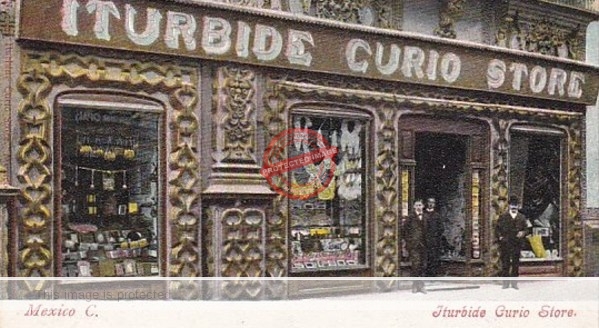

Educated Italian traveler Adolfo Dollero (1872-1936) resided in Mexico for many years. Though not published until 1911, his book México al día relates to travels in Mexico in 1907-10. The work is a large volume (almost a thousand pages) and covers almost the entire country, with details of activities, ranches, villages, towns and cities, together with a partial listing of hotels and significant stores and services. Dollero was interested in the economic opportunities Mexico offered, and considered that improved transport routes would allow the nation’s natural wealth, mines, caves, lakes, coast and rivers to be fully exploited.

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.

Towards the end of 1914, the difficult political circumstances in Mexico caused the family to relocate to Cuba, where they remained until 1921, when they returned to Mexico. The family also lived for periods of time in Colombia and Venezuela. Dollero died in Mexico City in September 1936.

In migration records, Dollero described his profession variously as “publicist”, “publisher”, “author” or “press.” A Colombian book by Rito Rueda Rueda describes Dollero as a historiographer who agreed with the opinion of the geographer Eliseo Reclus “that all the native Americans belong to the same ethnic group despite their diversity of customs and their four hundred languages.”

The title page of México al día refers to future English, French, Italian and German editions of the book; however, only the Italian edition ever saw the light of day, and not until 1914. Dollero also wrote books on Cuba (1916, 1919, 1921), Colombia (1930) and Venezuela (1933).

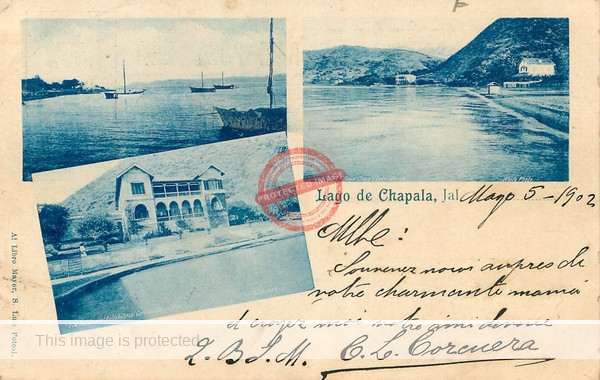

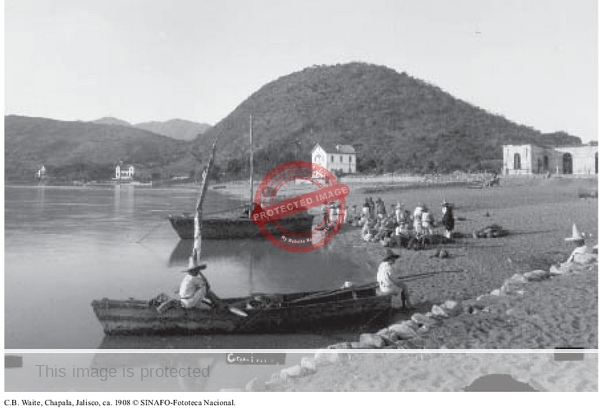

His account of the Lake Chapala area, which he visited in 1909, includes descriptions of the towns, climate and fertility of the lakeshore, as well as the gold and silver mines in the area, and the names of the major landowners. The only hotel listed for the “bathing resort of Chapala,” is the Hotel La Palmera, managed by Francisco Mántice, and the only store he lists is Juan Sanchez é hijos, selling ‘Ropa y Abarrotes’ at the intersection of calle Muelle (now Avenida Francisco I Madero) and calle Agua Caliente (now Avenida Hidalgo).

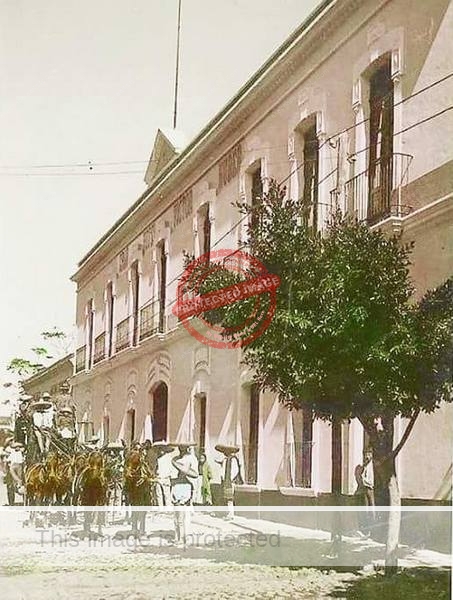

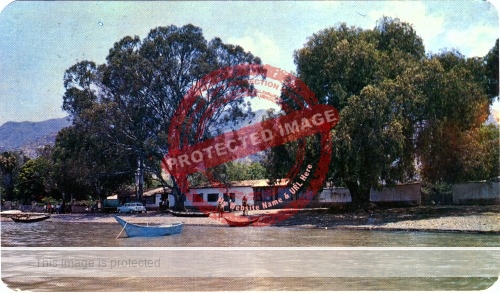

Dollero stayed at the Hotel Palmera—designed by Guillermo de Alba for owner Ignacio Arzapalo— which had opened in 1908 adjacent to the Hotel Arzapalo. (One section of the Hotel Palmera later became the Hotel Nido, which was acquired by the Chapala municipality in 2001 for its main municipal offices.)

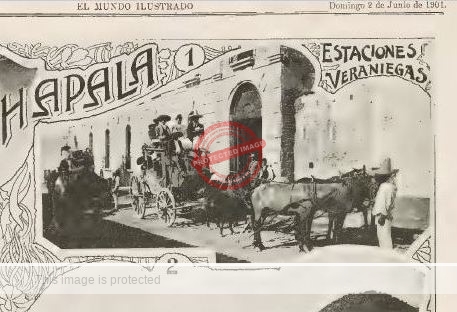

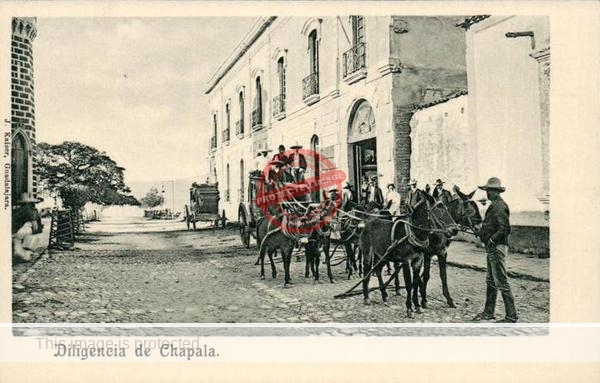

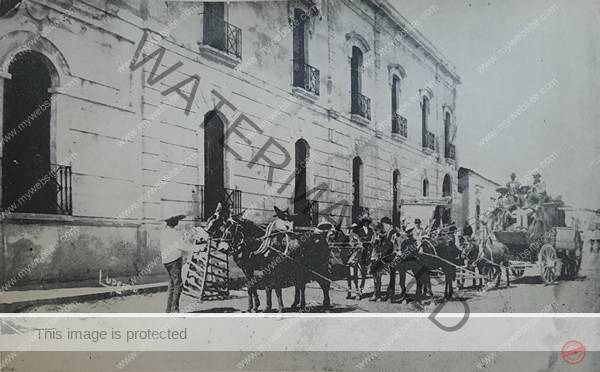

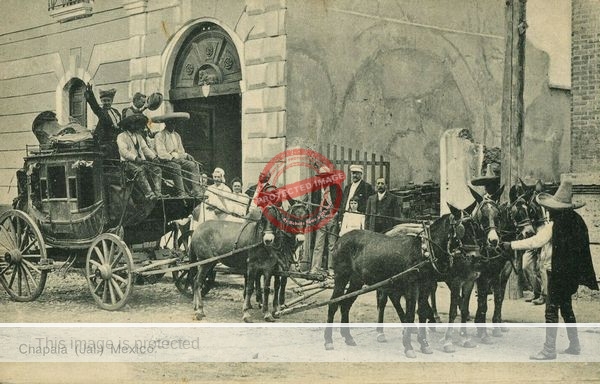

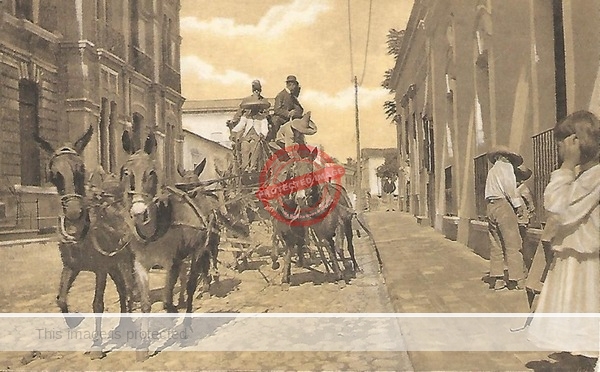

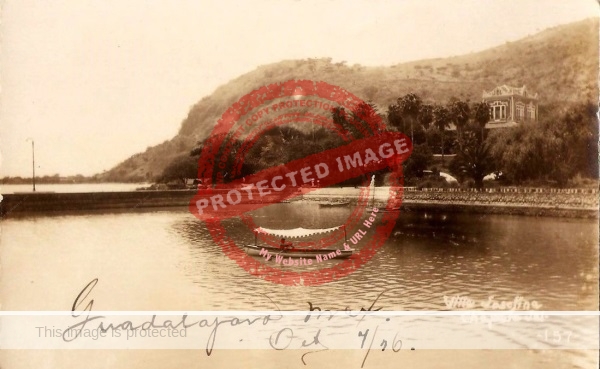

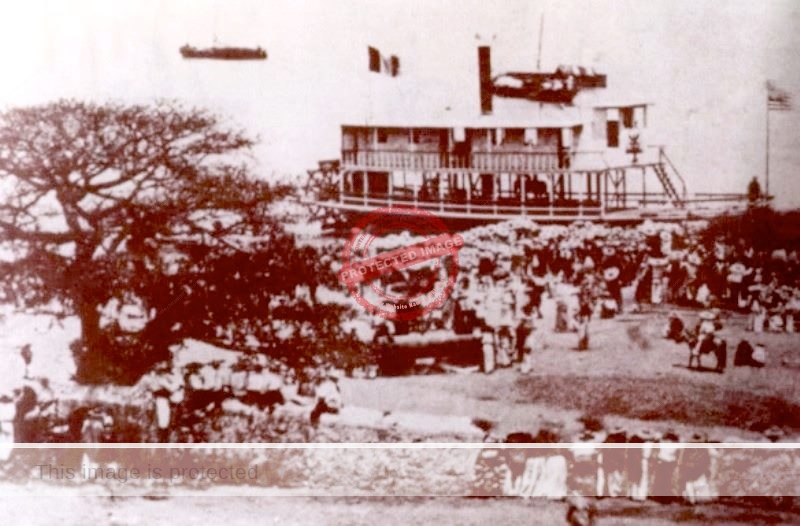

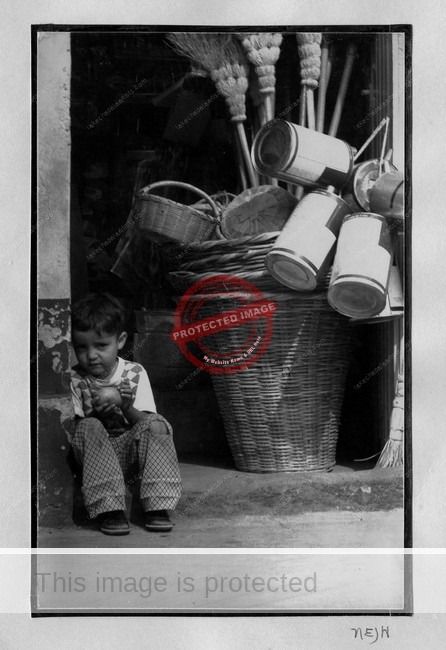

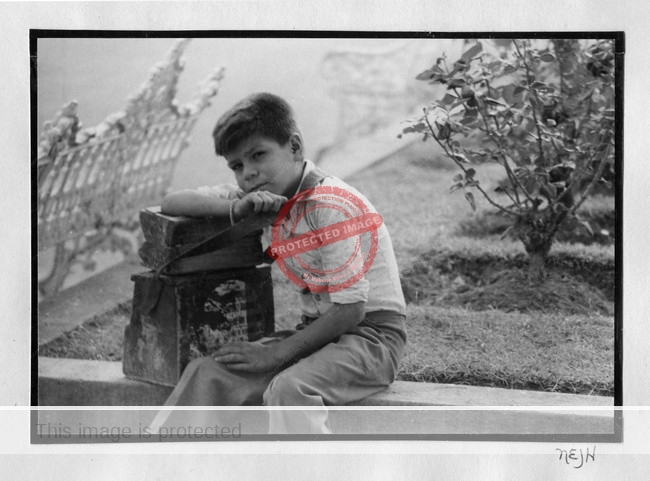

José María Lupercio. Chapala, c. 1907. (Dollero p 435)

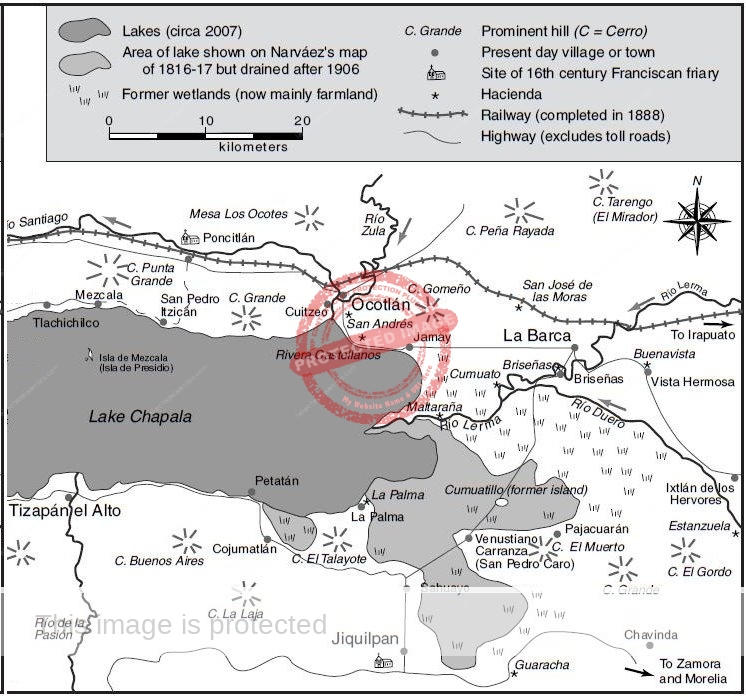

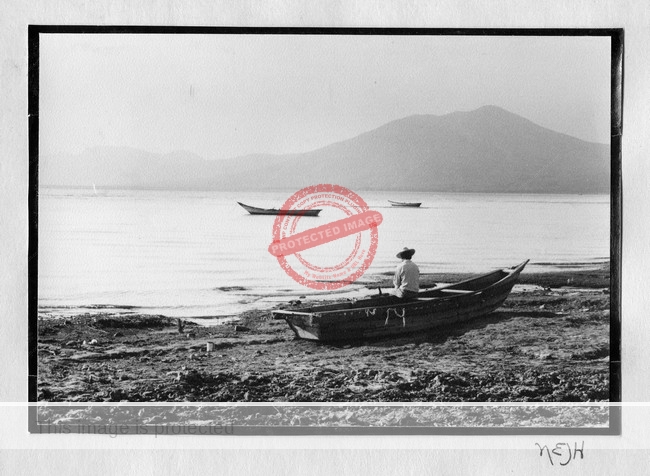

Dollero’s account of the Chapala region is illustrated with four small photographs: one (above) credited to “Jup.” (sic) (= José María Lupercio) and three—The Isla del Presidio, aka Mezcala Island; a chalet on the lakeshore (Casa Capetillo); and boats in Ocotlán—credited to Winfield Scott.

The following excerpts from México al día (translations by author) give a sense of what most interested Dollero:

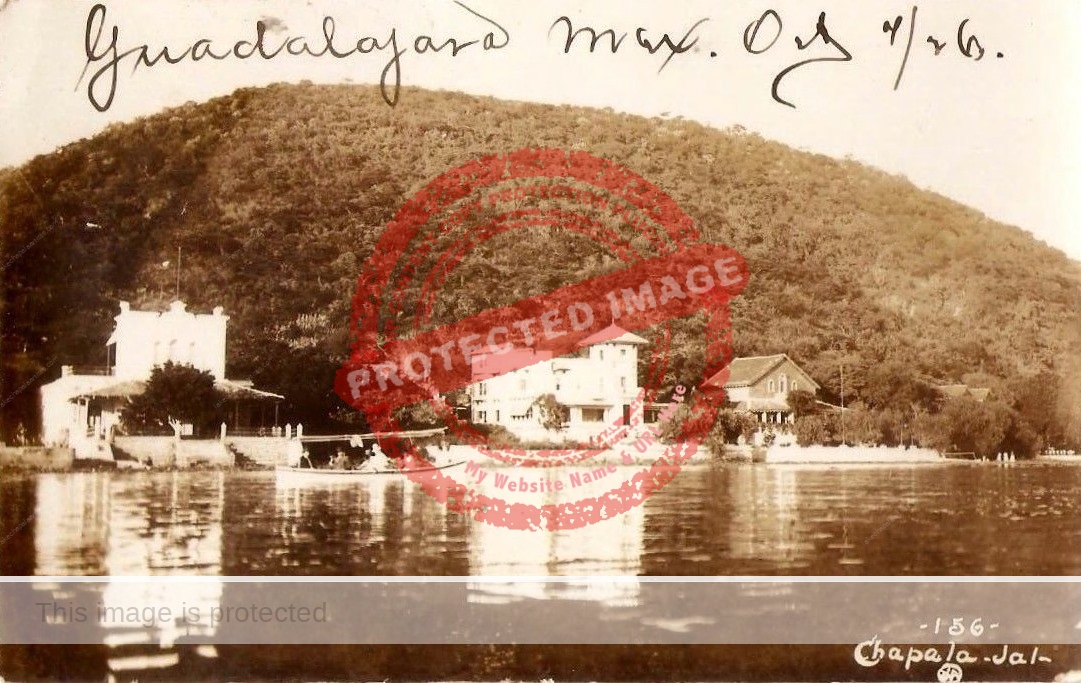

Chapala is a village of no more than 3000 inhabitants, but its privileged location and truly unbeatable climate have made it the meeting place for the most important Mexican families, especially those from the Republic’s capital and Guadalajara.

On the shores of the lake, or at the foot of the hills that are reflected in its water, are magnificent chalets. The President of the Republic, General Porfirio Díaz, himself likes to spend some vacation time here at the end of Lent in the company of his close friends. Then the lake acquires a special liveliness: hundreds of steam launches and boats plow through the water in every direction; everywhere there are high society parties and lots of money is spent. It is a shame that this liveliness has been, up to now, very short lived; it has always been restricted to a few months of the year, perhaps on account of the communication difficulties.

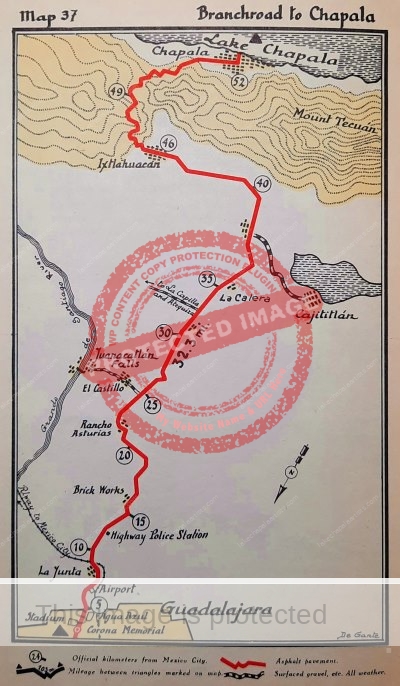

From the station at Atequiza, we were shaken for more than two and a half hours in an uncomfortable diligence, which was certainly not very agreeable. They assured us, however, that within a short time a branch line of the railroad would be started to remove the only obstacle which up to now has prevented Chapala from being a place of happiness year round.

We were staying in the hotel La Palmera, belonging to a congenial Italian citizen Mr. Francisco Mantice. The hotel was first rate and the cooking, distinctly French and Italian, was therefore very satisfying.

Chapala has, in general, good land, especially that which is on the shores of the lake; some fields are less fertile than others. Besides dedicating themselves to agriculture, the inhabitants also fish; fine fish are abundant, as are turtles and various species of aquatic birds, some of them valued highly for their very fine feathers.

Lake Chapala measures some 100 kilometers in length and its maximum width is 24 kilometers.

There are some mines for gold and silver in Ajijic, but, judging by what has been discovered in them up to now, they are not very rich. Some traces of petroleum have been found in the lake, but tests have shown it to be insufficient for exploitation.

The sand of the lake contains lots of quartz and silica and could be used for the manufacture of glass: there was already one bottle factory, which was closed down for lack of capital. Several thermal springs also exist in Chapala: one of them is ferruginous and another one sulfurous.

After two days in Chapala, Dollero departed for Ocotlán on board the small steamship Raúl:

Our voyage lasted four hours and proved extremely interesting. Black storm clouds were gathering on the horizon, and from time to time a ray of sunshine shone through them for a few moments to fleetingly illuminate the top of this or that greenish hill before becoming hidden again behind other clouds, still blacker and heavier . . . .

We passed a short way off the island of Alacranes and afterwards very close to Presidio Island, where we could clearly distinguish the old walls, almost destroyed, of the gaol that existed there long ago… The island appeared to be abandoned. Only a very short time after we had passed Presidio Island, we saw a huge vertical column shaped like an enormous serpent appear on the horizon.

We had the opportunity to see for the first time the phenomenon of a water spout, which greatly interested us, though we would have preferred to meet it on board a large steamer rather than the extremely fragile Raúl. However, the little steamer’s owner, who had not put down the telescope, calmed us down shortly afterwards, assuring us that the wind from the North that was blowing strongly at the time would have changed the direction of the water spout or would have destroyed it. In truth, some twenty minutes later, the column of water did become less dense, becoming gradually like a bow before disappearing completely. . . .

The left bank gradually acquired an extraordinary liveliness: house followed house; then came ranches and haciendas which they told us belonged to American citizens who had changed them into poetic residences with an abundance of flowers, fruit and cattle. A more enchanting landscape could not be planned.

At last, we entered the River Zula and then clearly saw the small churches of Ocotlán and to the right the Hotel Rivera Castellanos and the haciendas of El Fuerte, also extremely pleasant places, and very popular with North Americans, great lovers, as is known, of natural beauty.

Dollero then describes Ocotlán:

Ocotlán is a small town of 5000 inhabitants with a lot of commercial activity. The products of all the lake arrive here. Given this, it attracted our attention that there was no wharf and that the small steamers and different vessels had to moor alongside the trees on the banks! We were told, however, that a Mr. Ramón Flores, a person of initiative and capital, had requested authorization from the Secretariat of Communications and Public Works to build a suitable one within a short period of time.

Ocotlán is a true granary: since all the region is fertile, canoes come here from all directions with loads of cereals, fruit, matting of tule (an aquatic plant that is very abundant in these parts). On some occasions, the dozens of warehouses belonging to the Railway Company and private owners, and the wagons of the Tram Company, which sometimes transport up to 3000 loads a day—an enormous quantity considering that Ocotlán is more a town than a city—are not sufficient.

The countryside is splendid: irrigation, already practiced on a vast scale, will soon be on an even larger one, once the magnificent project of Mr. Manuel Cuesta Gallardo, for which the Federal Government has made important concessions, has been carried out.

Dollero then describes the proposed irrigation system, noting that the irrigation company will make a ‘fairly good profit’ by selling parcels of the land ceded to it by the Government, and that Cuesta Gallardo had reached ‘extra-judicial agreements’ with the most important of those landowners who had initially opposed the scheme. Dollero also commented on the likely high agricultural productivity of the reclaimed, irrigated land, for fruit trees, grapevines, chickpeas, corn and cattle.

In a later section, Dollero turns his attention to the resources found on the southern shore of the lake, and makes some pertinent observations:

The District of Jiquilpan, to which Cotija also belongs, is very rich. A short distance from Cotija are large deposits of iron oxides, zinc sulfides, copper sulfate and carbonate: the mountains have mica, talc or anhydrous magnesium silicate, and kaolin (hydrated aluminum silicate) for the manufacture of porcelain, etc.

There are also fine construction woods, many fruit trees, a large variety of medicinal plants, and the terrible weed that causes temporary madness, that is to say marijuana (Cannabis indica).

Near La Palma, on the shores of Lake Chapala, part of which belongs to the State of Michoacán, a lot of stone suitable for blade-sharpening is also found.

Source

- Dollero, Adolfo. 1911. México al día. (Impresiones y notas de viaje). Paris-Mexico: Librería de la Vda. de C. Bouret, 435-441, 456.

This post is based on chapter 51 of Lake Chapala Through the Ages: an anthology of travelers’ tales, which focuses on the period 1530-1910. For more recent history of the region, see Lake Chapala: A Postcard History.

Comments welcomed via email or via comments feature on this post.

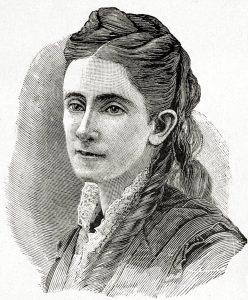

In “Lake Chapala,” Mary Ashley Townsend, looking across the waters of the lake from her stately residence, Villa Montecarlo, indulged her imagination and poetic talents.

In “Lake Chapala,” Mary Ashley Townsend, looking across the waters of the lake from her stately residence, Villa Montecarlo, indulged her imagination and poetic talents.