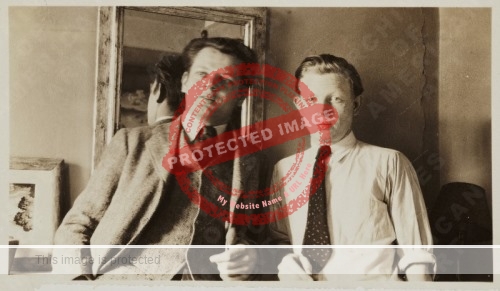

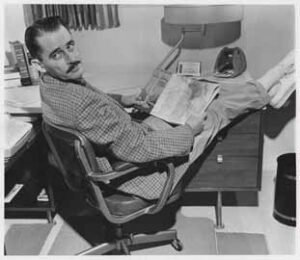

Author and poet Harold Witter Bynner (1881-1968), known as “Hal” to his friends, had a lengthy connection to Lake Chapala extending over more than forty years. He first visited the lake and the village in 1923, when he and then companion Willard Johnson were traveling with D.H. Lawrence and his wife.

Bynner returned to Chapala in 1925, and later (1940) bought a house there, which became his second home, his primary residence remaining in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Bynner spent two and a half years in Chapala during the second world war, and the equivalent of ten years of his life there in total.

Poet, mimic and raconteur Witter Bynner was born into a wealthy family. Apparently, he liked to recount stories about his mother, who, he claimed, kept $500,000 in cash in one of her closets.

He graduated from Harvard in 1902, having been on the staff of the Harvard Advocate.

Bynner published his first volume of verse, Young Harvard and Other Poems, in 1907. Other early works included Tiger (1913), The New World (1915), The Beloved Stranger (1919), A Canticle of Pan and Other Poems (1920), Pins for Wings (1920) and A Book of Love (1923).

In 1916, in an extended prank aimed at deflating the self-important poetry commentators of the time, Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke collaborated to perpetrate what has often been called “the literary hoax of the twentieth century”. Bynner and Ficke had met at Harvard and were to become lifelong friends. Ficke and his wife Gladys accompanied Bynner on a trip to the Far East in 1916-17. In 1916, Bynner writing under the pen name “Emanuel Morgan” and Ficke, writing as “Anne Knish” published a joint work, Spectra: A Book of Poetic Experiments. Intended as a satire on modern poetry, the work was enthusiastically reviewed as a serious contribution to poetry, before the deception was revealed in 1918. (Ficke, incidentally, later spent the winter of 1934-35 in Chapala, with Bynner, and wrote a novel set there: Mrs Morton of Mexico.)

Even though Bynner still became President of the Poetry Society of America from 1920 to 1922, the Spectra hoax was not well received by the poetry establishment, and Bynner’s later poetry received less attention than deserved.

Bynner traveled extensively in the Orient, and compiled and translated an anthology of Chinese poetry: The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology, Being Three Hundred Poems of the T’ang Dynasty 618–906 (1929) as well as The Way of Life According to Laotzu (1944). He also amassed an impressive collection of Chinese artifacts.

In 1919, he accepted a teaching post at the University of California at Berkeley. Students in his poetry class there included both Idella Purnell and Willard “Spud” Johnson. When Bynner left academia and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1922, to concentrate on his own writing, Johnson followed to become his secretary-companion. D. H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda stayed overnight with them on their way to Taos. Bynner, Johnson and the Lawrences traveled together to Mexico in the spring of 1923. After a short time in Mexico City, they settled in Chapala, where the Lawrences rented a house while Bynner and Johnson stayed at the Hotel Arzapalo.

Chapala with the Lawrences

Chapala with the Lawrences

Bynner’s memoir of this trip and the group’s time in Chapala is told in his engagingly-written Journey with Genius (1951), which is full of anecdotes and analysis. Among the former, for example, is the story told them by Winfield Scott, manager of the Arzapalo, who a few years earlier had been kidnapped by bandits who attacked the Hotel Rivera in El Fuente.

Bynner, who seems to have had near-perfect recall, describes Chapala and their trips together in loving detail, as well as providing insights into Lawrence’s work habits and mood swings. For his part, Lawrence appears to have been less than impressed, since in The Plumed Serpent he used Bynner as the basis for the unflattering character of Owen, the American at the bullfight.

Bynner’s poem about Lawrence in Chapala, “The Foreigner”, is short and sweet:

Chapala still remembers the foreigner

Who came with a pale red beard and pale blue eyes

And a pale white skin that covered a dark soul;

They remember the night when he thought he saw a hand

Reach through a broken window and fumble at a lock;

They remember a tree on the beach where he used to sit

And ask the burros questions about peace;

They remember him walking, walking away from something.

The Lawrences left Chapala in early July 1923, but Bynner and Johnson stayed a few months more, so that Bynner could continue working on his book of verse, Caravan (1925).

Bynner returned to Chapala in 1925, and a letter from that time shows how he thinks the town has changed, in part due to tourists: “Too much elegancia now, constant shrill clatter, no calzones, not so many guaraches, no plaza-market.” Among the changes, Bynner noted several other American writers and a painter in Chapala, making up “a real little colony” (quoted in Delpar).

Bynner returned to Chapala in 1925, and a letter from that time shows how he thinks the town has changed, in part due to tourists: “Too much elegancia now, constant shrill clatter, no calzones, not so many guaraches, no plaza-market.” Among the changes, Bynner noted several other American writers and a painter in Chapala, making up “a real little colony” (quoted in Delpar).

Elsewhere, diary entries and other letters reveal why he liked Chapala: “The Mind clears at Chapala. Questions answer themselves. Tasks become easy”, and how he felt at home there: “Me for Chapala. I doubt if I shall find another place in Mexico so simpatico.”

Poems related to these first two visits to Chapala (1923 and 1925) include “On a Mexican Lake” (New Republic, 1923); “The Foreigner” (The Nation, 1926); “Chapala Poems” (Poetry, 1927); “To my mother concerning a Mexican sunset / Mescala etc.” (Poetry, 1927); “Indian Earth” [Owls; Tule; Volcano; A Sunset on Lake Chapala; Men of Music; A Weaver from Jocotepec] (The Yale Review, 1928); and “Six Mexican Poems” [A Mexican Wind; A Beautiful Mexican; From Chapala to a San Franciscan; The Cross on Tunapec; Conflict; The Web] (Bookman, 1929).

Bynner included many of these poems in the collection Indian Earth (1929), which he dedicated to Lawrence, and which many consider some of Bynner’s finest work. A reviewer for Pacific Affairs (a journal of the University of British Columbia, Canada), wrote that “Chapala, a sequence occupying over half the seventy-seven pages of the book, is a poignant revelation to one in quest of the essence of an alien spirit, that alien spirit being in this case the simple, passionate Indian soul of old Mexico.”

Among my personal favorites (though I admit to bias) is

A Weaver From Jocotepec

Sundays he comes to me with new zarapes

Woven especial ways to please us both:

The Indian key and many-coloured flowers

And lines called rays and stars called little doves.

I order a design; he tells me yes

And, looking down across his Asian beard,

Foresees a good zarape. Other time

I order a design; he tells me no.

Since weavers of Jocotepec are the best in Jalisco,

And no weaver in Jocotepec is more expert than mine,

I watched the zarapes of strangers who came to the plaza

For the Sunday evening processions around the band,

And I showed him once, on a stranger, a tattered blanket

Patterned no better than his but better blent––

Only to find it had taken three weavers to weave it:

My weaver first and then the sun and rain.

Later Chapala-related poems by Bynner include “Chapala Moon and The Conquest of Mexico” (two poems; Forum and Century, 1936) and “Beach at Chapala” (Southwest Review, 1947).

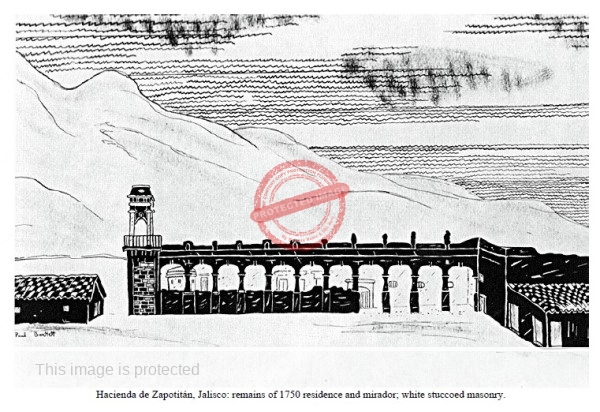

Bynner’s third trip to Chapala, with partner Robert (“Bob”) Hunt (1906-1964), came in 1931. The pair visited Taxco and Chapala, but Bynner preferred Chapala, claiming (somewhat in contradiction to his earlier letter about a “real little colony”) that, “Chapala survives without a single foreigner living there and, despite its hotels and shabby mansions, continues to be primitive and feel remote.” Of course, this was by no means true; there certainly were foreigners living in Chapala in 1931, including some who had been there since the start of the century.

When Bynner returned to Chapala for a longer stay in January 1940, he first stayed at the Hotel Nido, but not finding it much to his liking soon purchased a house almost directly across the street. The original address was Galeana #411, but the street name today is Francisco I. Madero. We consider the history of this house in a separate post, but Bynner and Hunt regularly vacationed here thereafter.

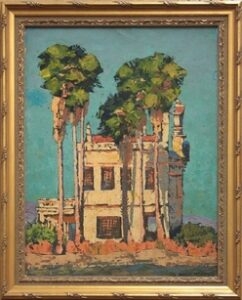

At some point in mid-1944, Bynner had been joined at Chapala by a young American painter Charles Stigall, whose ill health at the time had caused him not to be drafted. He lived with Bynner while he recuperated. Certainly he was there in November 1944, as the Guadalajara daily El Informador (19 November 1944) records both “Mr Witter Bynner, famous American poet” and “Mr Charles Stigel” attending an exhibition of Mexican paintings by Edith Wallach, at the Villa Montecarlo. Among the other guests, at the opening were Nigel Stansbury Millett (one half of the Dane Chandos writing duo); Miss Neill James; Mr Otto Butterlin and his daughter Rita; Miss Ann Medalie; and Mr. Herbert Johnson and wife. (The newspaper makes no mention of Bob Hunt, who was also in Chapala at that time).

In November 1945, Bynner lost his oldest and closest friend, Arthur Ficke. The following month, he returned to Chapala for the winter.

Bynner and Hunt continued to visit Chapala regularly for many years, into the early 1960s. He was well aware of how much the town had changed since his first visit in 1923. For example in a letter to Edward Nehls in the 1950s, Bynner wrote,

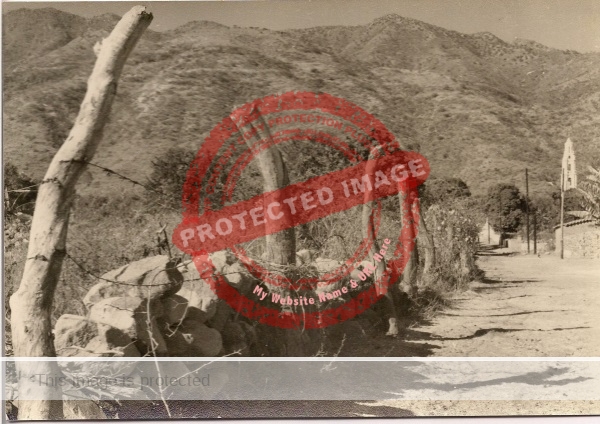

“The “beach” where Lawrence used to sit, is now a severe boulevard [Ramon Corona] which gives me a pang when I remember the simple village we lived in. The tree under which he sat and wrote is gone long since and the beach close to it where fishermen cast nets and women washed clothes has receded a quarter of a mile. But the mountains still surround what is left of the lake and, as a village somewhat inland, Chapala would still have charmed us had we come upon it in its present state.”

In February 1949, Bynner had his first slight heart attack, but still visited Chapala for part of the year. At about this time, his eyesight began to deteriorate. Bynner and Hunt, in the company of artist Clinton King and his wife Narcissa, traveled to Europe and North Africa for the first six months of 1950, visiting, among others, Thornton Wilder and James Baldwin in Paris, and George Santayana and Sybille Bedford (author of a fictionalized travelogue about Lake Chapala) in Rome.

Bynner’s final years were spent in ill-health. Bynner had almost completely lost his sight by January 1964, when he unexpectedly lost his long-time partner, Bob Hunt, who had a fatal heart attach just as he was setting out for Chapala, having made arrangements for Bynner to be cared for in his absence by John Liggett Meigs.

The following year, Bynner suffered a severe stroke. While friends cared for him for the remainder of his life (he died in 1968), Bynner’s doctors ordered that the famous poet was not well enough to receive visitors for more than one minute at a time.

Bynner left his Santa Fe home to St. John’s College, together with the funds to create a foundation that supports poetry. The house and grounds are now the Inn of the Turquoise Bear.

His passing marked the loss of one of the many literary greats who had found inspiration at Lake Chapala.

Sources:

- Bushby, D. Maitland. 1931. “Poets of Our Southern Frontier”, Out West Magazine, Feb 1931, p 41-42.

- Bynner, Witter. 1951. Joumey with Genius: Recollection and Reflections Concerning The D.H. Lawrences (New York: The John Day Company).

- Bynner, Witter. 1981. Selected Letters (edited by James Kraft). The Works of Witter Bynner. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

- Delpar, Helen. 1992. The Enormous Vogue of Things Mexican : Cultural Relations between the United States and Mexico, 1920-1935. (University of Alabama Press)

- Kraft, James 1995. Who is Witter Bynner? (UNM Press)

- Nehls, Edward (ed). 1958. D. H. Lawrence: A Composite Biography. Volume Two, 1919-1925. (University of Wisconsin Press).

- Sze, Corinne P. 1992. “The Witter Bynner House” [Santa Fe], Bulletin of the Historic Santa Fe Association, Vol 20, No 2, September 1992.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

![l to r: Robert Hunt, Galdys Ficke, Arthur Ficke, ca 1935. [Source: Kraft: "Who is Witter Bynner"?]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/hunt-robert-with-fickes-chapala-1934-5s.jpg)

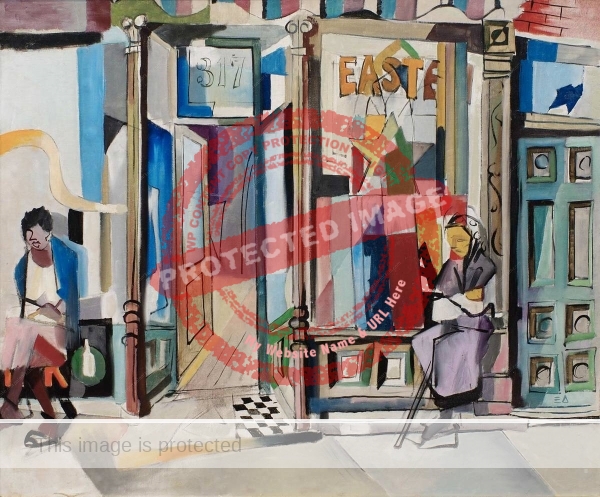

Painting #2:

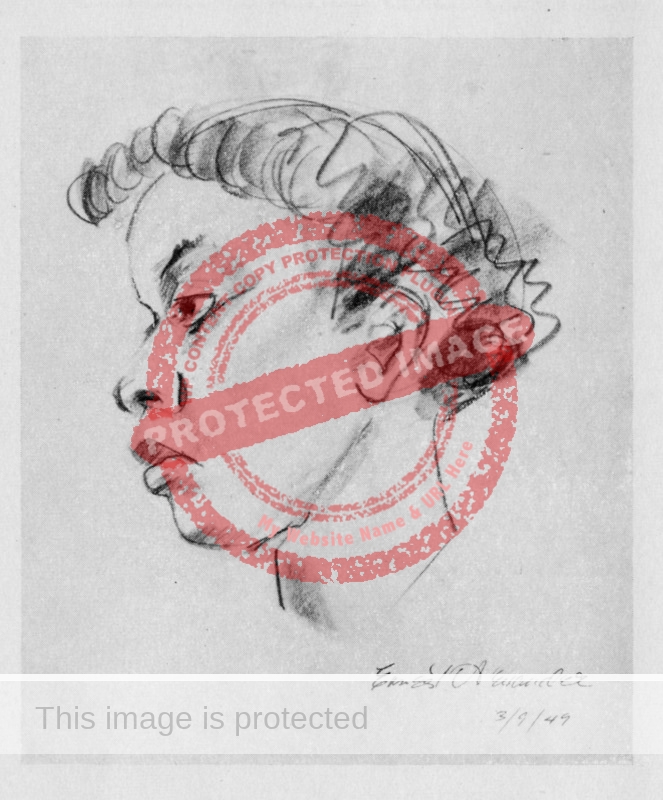

Painting #2: Painting #3

Painting #3