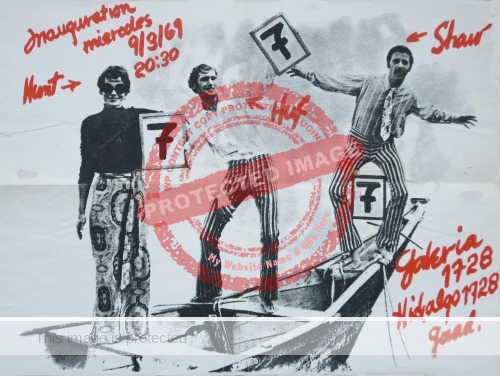

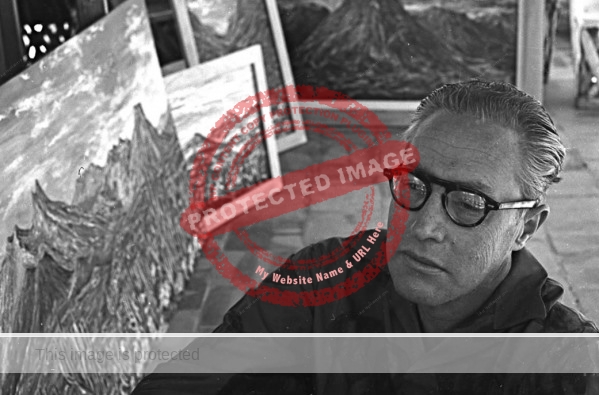

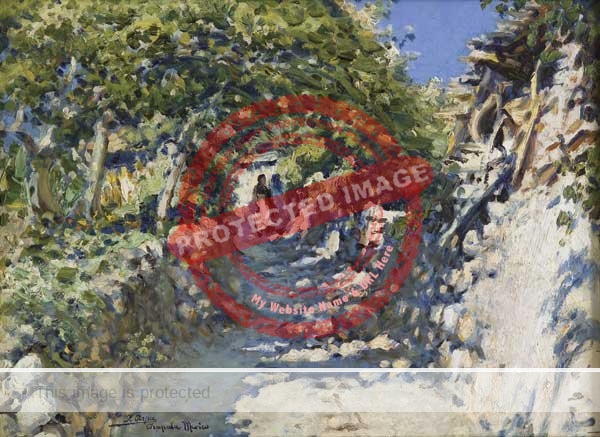

American artist Peter Hurd (1904-1984) spent most of his life in New Mexico, but also had connections to Lake Chapala. In about 1968, together with fellow artist and former student John Liggett Meigs, Hurd bought the home in Chapala previously owned by poet Witter Bynner. Although there is no evidence that Chapala influenced Hurd’s work in any way, the artist visited Chapala on several occasions, and presumably was accompanied on some of these trips by his wife, artist Henriette Wyeth.

Hurd had life-long ties to New Mexico. He was born on 22 February 1904 in Roswell and died there on 9 July 1984. His parents named him Harold Hurd Jr., but called him “Pete” and, in his early 20s, he legally changed his name to Peter.

In 1918, he studied at New Mexico Military Institute, and three years later entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. In 1923, he left West Point to study at Haverford College in Pennsylvania. Soon afterwards, Hurd settled in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, so that he could study art under the illustrator N.C. Wyeth. He worked for a decade as Wyeth’s assistant and, in 1929, married Henriette Wyeth, Wyeth’s eldest daughter.

The couple moved back to Hurd’s native New Mexico and established the family home and studios on a ranch in San Patricio. Henriette Wyeth later became very well-known for her own portraits and still life paintings, “considered by many art scholars to be one of the great women painters of the 20th century”. Two of the couple’s children, Ann Carol Hurd and Michael Hurd, also became professional artists and continue to live on the family ranch in San Patricio.

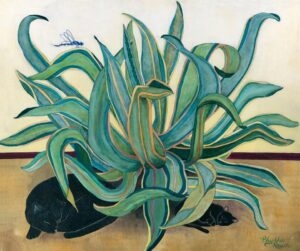

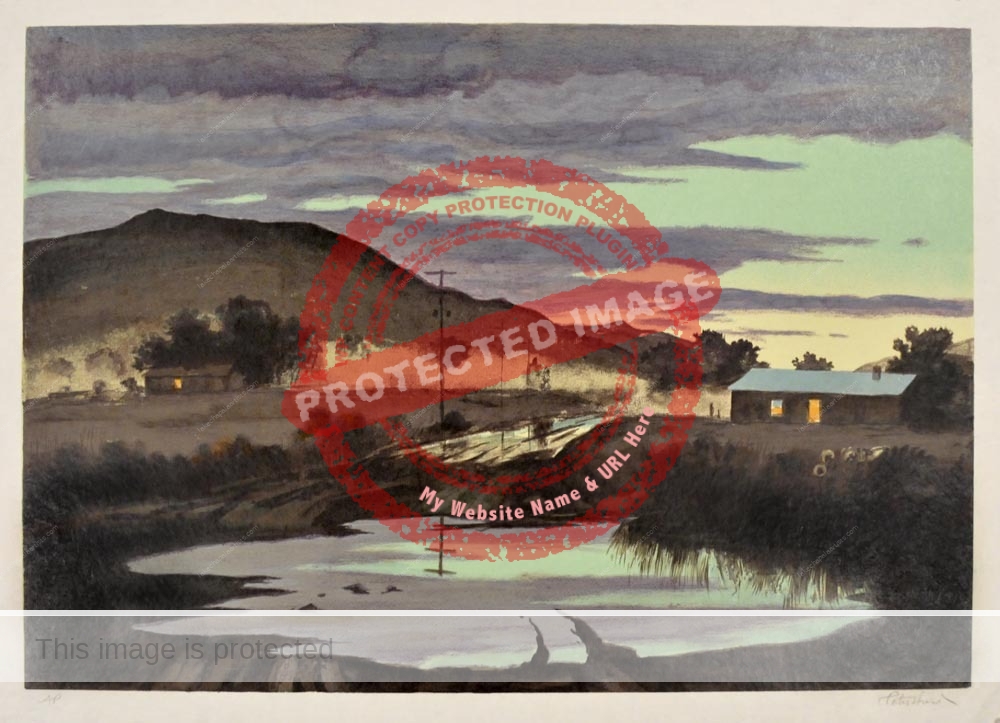

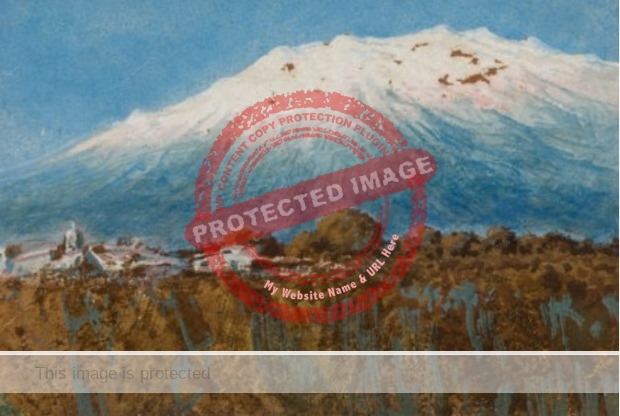

Many of Peter Hurd’s works are set in Southeastern New Mexico, in and around the ranch in San Patricio and in the Hondo Valley:

In the 1930s, during the depression, Hurd focused on producing inexpensive lithographs for a larger audience. Convinced of the need for gallery representation in New York, he drove there with a portfolio and quickly convinced several gallery owners to display his lithographs.

During the second world war, Hurd was a war correspondent for Life. He became a full member of the National Academy of Design in 1942. Hurd’s wartime works varied from quick plein air sketches to watercolors and egg temperas (his preferred medium). After the war, Hurd traveled in North Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

From 1953 to 1954, Hurd, together with Henriette and two of his students – Manuel Acosta and John Meigs – painted a fresco in Lubbock, Texas, at the West Texas Museum (now the Holden Hall at the Texas Tech University). The mural depicts pioneers and influential leaders of West Texas, and includes a self-portrait of Hurd himself, sketchpad in hand.

A later Hurd mural, “The Future Belongs To Those Who Prepare For It”, was saved from destruction when its original location, the Prudential Building in Houston, Texas, was about to be demolished. It was rehoused in 2011 in the Artesia Public Library in New Mexico. The story of how the mural was moved makes for interesting reading.

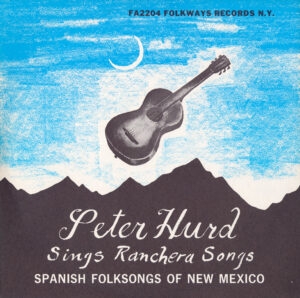

Hurd was also an accomplished musician. In 1957, he collaborated with Folkways Records to release an album, Spanish Folk Songs of New Mexico, on which Hurd played the guitar and sang the lyrics (Spanish and English) of various ranchera songs.

From 1959 to 1963, at the invitation of President Eisenhower, Hurd served on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts.

Hurd’s first major retrospective exhibition, in 1964/65, was held at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. The catalog for the exhibit, entitled Peter Hurd : A Portrait Sketch from Life (1965) was written by Paul Horgan, a lifelong friend.

A 1967 portrait of Lyndon B. Johnson by Hurd, meant to be the president’s official portrait, did not find favor with its subject, but remains in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. The debate about the painting generated plenty of press coverage, which brought Hurd’s art to a much wider public.

Hurd illustrated several books, including The Story of Siegfried by James Baldwin (1931), and the same author’s The Story of Roland (1957); Hans Brinker or the Silver Skates by Mary Mapes Dodge (1932); Deep Silver. A story of the cod banks, by Nora Burglon (1939); Great Stories of the Sea and Ships, edited by N.C. Wyeth (1940); Murder and Mystery in New Mexico by Erna Fergusson (1948); Sky Determines by Ross Calvin (1948); Montana: high, wide, and handsome, by Joseph Kinsey Howard (1974). Hurd’s portrait of Charles C. Tillinghast, Jr. for the cover of Time (22 July 1966) was featured in a 1969 National Portrait Gallery exhibit of the magazine’s cover art.

Books about Hurd’s work include The Peter Hurd Mural (1957); Peter Hurd. The Lithographs, edited by John Meigs (1968); Peter Hurd sketch book, edited by John Meigs (1971); Peter Hurd: Insight to a Painter, by James K. Ballinger and Tonia L Horton (1983); My Land Is the Southwest: Peter Hurd Letters and Journals, edited by Robert Metzger (1983); Peter Hurd: A Memorial Exhibition, by Walt Wiggins (1984); The Art of Peter Hurd from the Permanent Collection, Roswell Museum (1985);

Hurd’s work can be found in many major museums and collections, including the Metropolitan Museum; Art Institute of Chicago, Brooklyn Museum, Roswell Museum, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico, and the National Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Sources:

- Mark S. Fuller. 2015. Never a Dull Moment: The Life of John Liggett Meigs.

- John Meigs (ed). 1968. Peter Hurd. The Lithographs.

- Chronological Biographies of the Wyeth Hurd Family Artists

- Peter Hurd (1904-1984)

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Chapter 11 is about a religious procession to the cemetery (campo santo) on the hillside:

Chapter 11 is about a religious procession to the cemetery (campo santo) on the hillside:

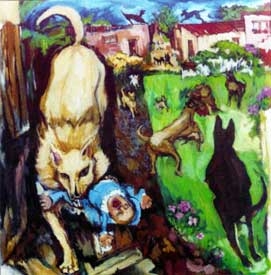

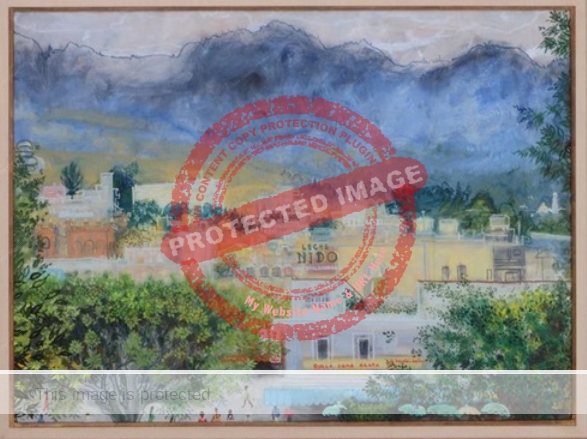

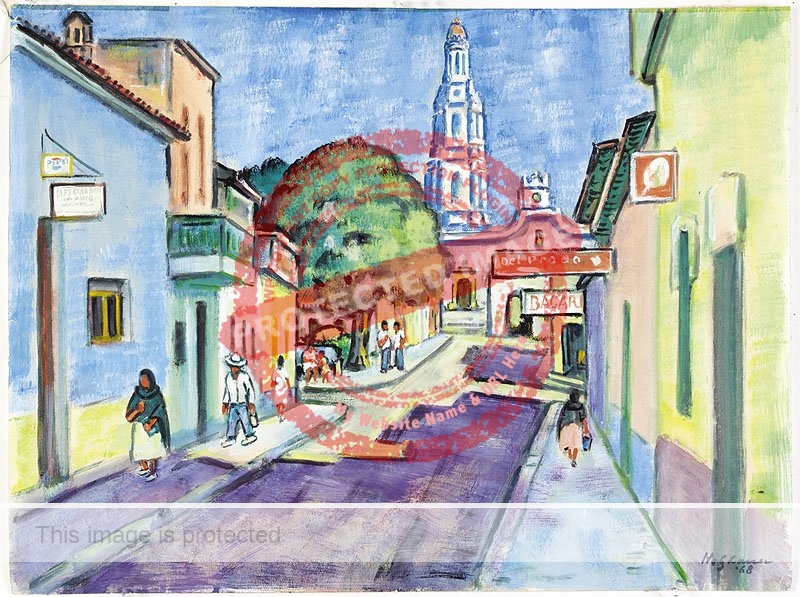

Painting #2:

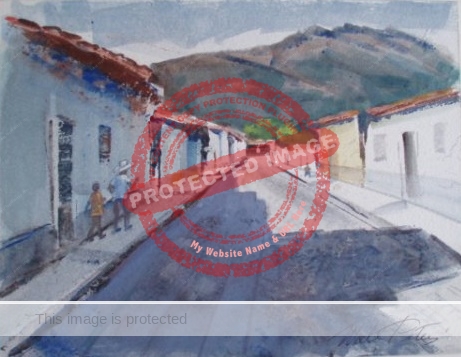

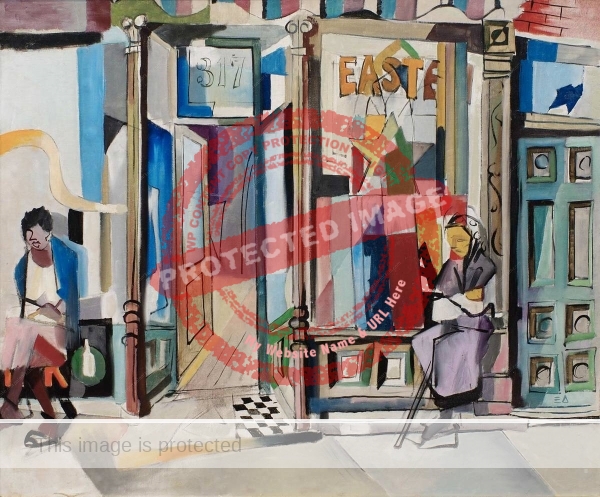

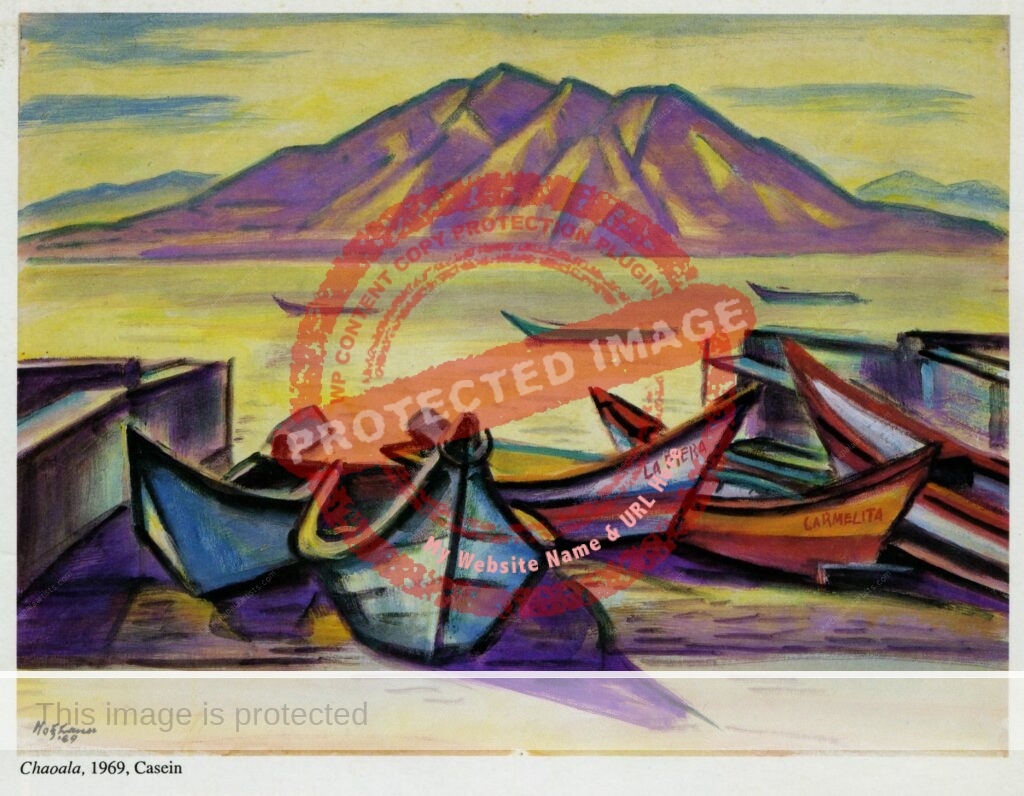

Painting #2: Painting #3

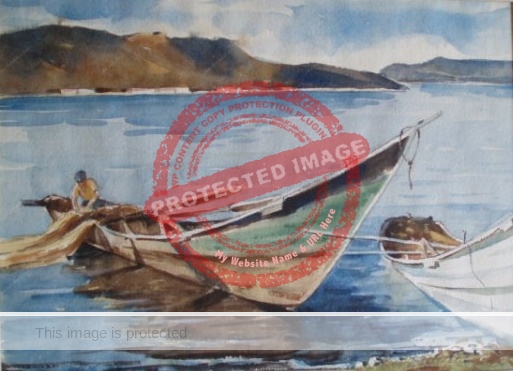

Painting #3