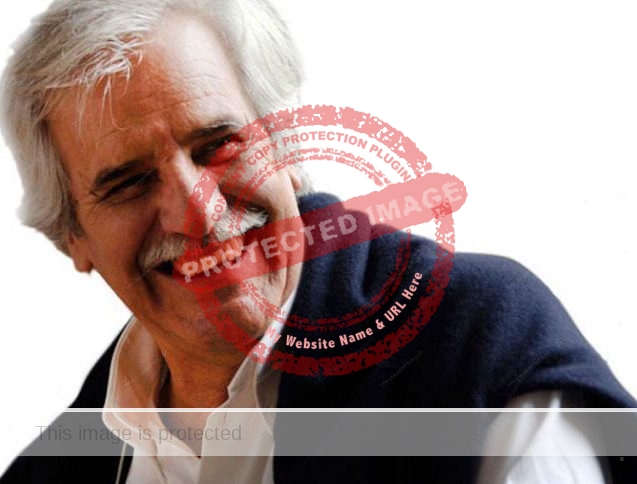

German engineer and photographer Helmuth A. Wellenhofer lived with his wife, Antonia (“Toni”) in Jocotepec for many years in the 1970s.

Helmut (as he was known in Mexico) was born in Bavaria in 1935. After completing his studies, he worked in a fashion house, became interested in literature, modern art and music, and founded a jazz group. In 1960, he crossed the Atlantic to Canada where he worked in a sawmill, warehouses and mines.

He became a passionate and serious photographer, undertaking trips to Alaska, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Sumatra and India. He visited Mexico for the first time in 1962 and planned to return, but only after visiting Panama, Germany and several other European countries, as well as seeing more of the U.S. and Canada.

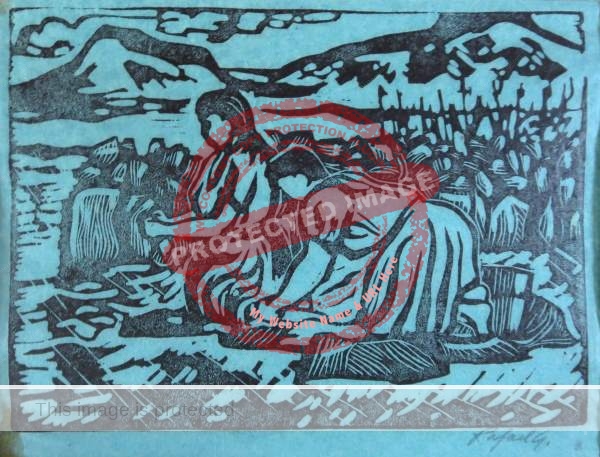

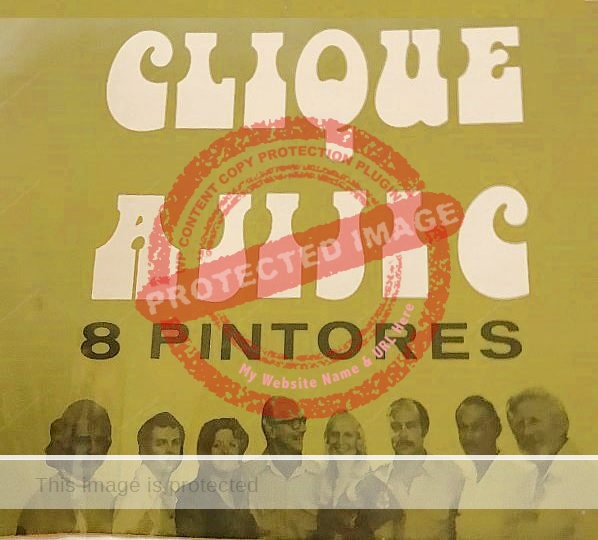

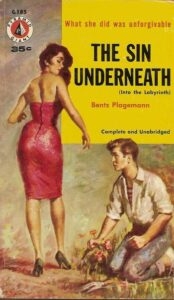

Poster for 1976 exhibition

On 17 August 1965 he married Antonia Bruggner, then aged 23, in Santa Barbara, California. The couple settled in Santa Barbara for several years and had a son, Andreas. Helmuth managed the Coral Casino Beach Club and Antonia worked with a title insurance firm.

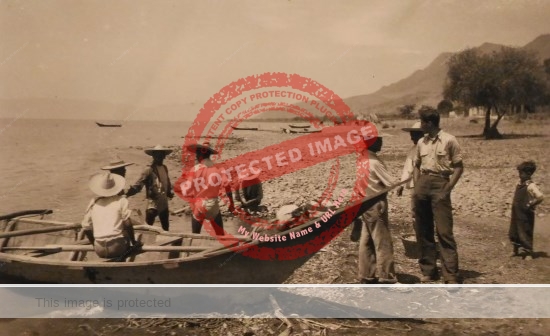

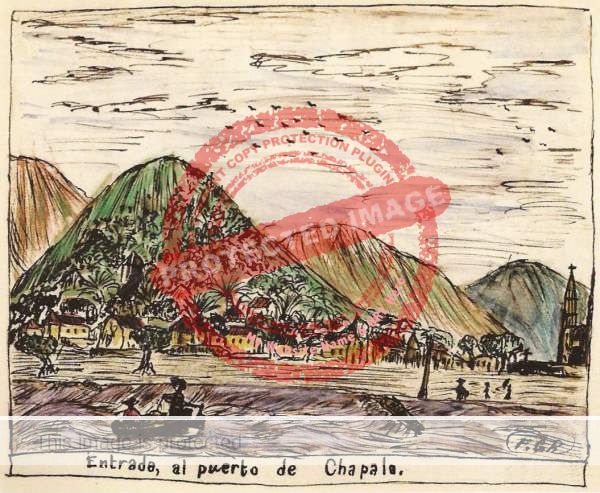

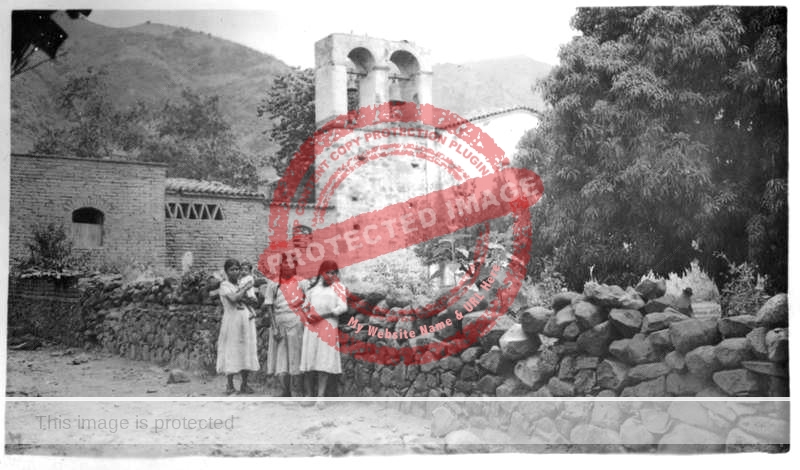

The Wellenhofers, with their young son, returned to live in Jocotepec on Lake Chapala in 1973. They became close friends with photographer John Frost and his novelist wife Joan Van Every Frost, whose son, John, was of similar age to Andreas. Both families spent Easter 1973 at the beach and in the surf at Tenacatita.

The Wellenhofers built a house in Nestipac and later sold the upper part of the property to another couple who eventually became long-time Jocotepec residents: Austrian artist Georg Rauch and his wife, Phyllis.

In 1975, Wellenhoffer embarked on a photographic railroad excursion to Los Mochis and the Copper Canyon and back. This was the basis for a fascinating exhibit which opened the following May at the Goethe Institute in Guadalajara.

That exhibition, entitled “Impresiones de un Viaje en México” featured photos from throughout Mexico, including Wellenhofer’s train trips along the west coast and through the Copper Canyon.

Wellenhofer summarized his railroad experiences for the local weekly newspaper, the Colony (Guadalajara) Reporter:

“Freight train 656 gets a “go” signal via shortwave radio and jerks slowly out of Guadalajara. After a few street crossings, the four-engine, 62-boxcar convoy picks up speed and we roll through the open countryside. I’m sitting in the third engine – my camera ready – and am happy to finally be on the track again.

Maybe it’s because I was born in a train station that I feel such an affinity for rail travel. I’ve ridden Japan’s “superfast”, spent three days inside a closed cattlecar in India and recall an unbelievable trip through Bolivia where male passengers were given reduced fare if they helped to chop wood for the engine.

My Mexican odyssey began when I approached the director of Ferrocarriles del Pacifico with a plan to travel the nation’s passenger and freight trains, documenting my journey with photographs. He approved and issued me a letter of introduction, instructing stationmasters and train personnel to help me along the way.

Armed with the letter I hopped aboard my first freight train in Guadalajara – bound for Tepic. En route, engineers and brakemen came by to talk, curious about my rail journey with a camera….”

At Tepic, Wellenhofer “switched to a freight train for a six-hour run to Mazatlán, riding alone in the last compartment of a 70-car convoy.” In Mazatlán he “hopped aboard a three-engine train barrelling 56 miles per hour to the railroad junction at Sufragio” where he boarded a second-class train through the Copper Canyon to Chihuahua.

From Chihuahua, he took the mid-night train to Zacatecas, in case full of “families, boxes, people sleeping on the floor, crying babies and moaning grandmothers.”

According to the poster for that show, he was then working on a collection of photos and poems about his impressions and perspectives.

The Wellenhofers were regular return visitors to Jocotepec for many years after moving from Mexico to Germany. Their son, Andreas Noar Wellenhofer is a professional saxophonist. (Enjoy his videos on Youtube)

Acknowledgments

- My thanks to the late John Frost Sr, and to John Frost Jr., Phyllis Rauch and Peter Huf for sharing their memories of the Wellenhofers.

Sources

- Colony (Guadalajara) Reporter: 14 April 1973; 6 Sep 1975; 24 April 1976, 14; 1 May 1976, 11, 14, 18.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Szekely was born in Máramarossziget in what was then Hungary (now Romania) on 5 March 1905 and died in 1979 in Costa Rica.

Szekely was born in Máramarossziget in what was then Hungary (now Romania) on 5 March 1905 and died in 1979 in Costa Rica. For Biogenic living, Szekely argued that people’s daily diet should consist of 25% biogenic foods (life renewing; eg germinated cereal seeds, nuts; sprouted baby greens); 50% bioactive foods (life sustaining; eg organic, natural vegetables, fruit) and 25% biostatic (life slowing; eg cooked and “stale” foods). They should avoid biocidic foods, such as processed and irradiated foods and drinks, since these were “life destroying.” In addition to this diet, Biogenic living also includes meditation, simple living, and respect for the earth in all its forms.

For Biogenic living, Szekely argued that people’s daily diet should consist of 25% biogenic foods (life renewing; eg germinated cereal seeds, nuts; sprouted baby greens); 50% bioactive foods (life sustaining; eg organic, natural vegetables, fruit) and 25% biostatic (life slowing; eg cooked and “stale” foods). They should avoid biocidic foods, such as processed and irradiated foods and drinks, since these were “life destroying.” In addition to this diet, Biogenic living also includes meditation, simple living, and respect for the earth in all its forms.

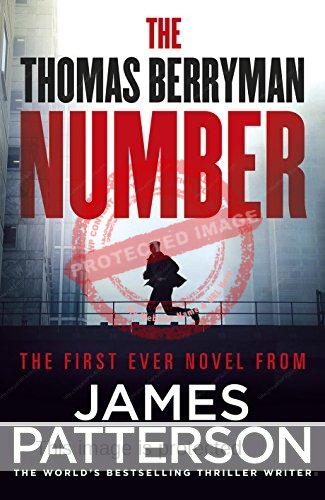

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.