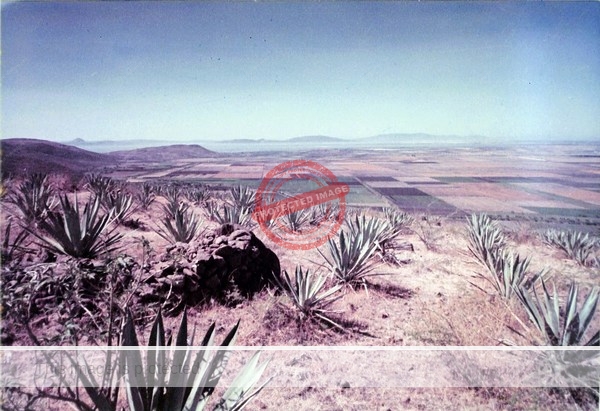

Visual artist and architectural designer Tom (“Tomas”) Faloon first arrived in Ajijic in 1970 and lived and worked in the village for more than forty years.

John Thomas Faloon was born on 30 January 1943 in New York City. After graduating in 1960 from Oakwood Friends School, a Quaker college preparatory school in Poughkeepsie, New York, he enrolled in Rutgers University. He traveled to Florence, Italy, to study art the following year, returning with fluent Italian and a determination to pursue art as a career. In the summer of 1962, he took a summer course at the Douglass College campus of Rutgers with the renowned modern artist Roy Lichtenstein. Faloon transferred to the University of Mississippi, “where the faculty of the time was young and progressive”.

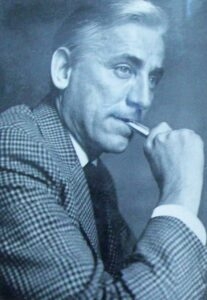

Tom Faloon, 1965 (Univ. of Mississippi Yearbook)

Faloon had only just arrived on the Mississippi campus when the Ole Miss race riot of 1962 erupted, following the enrollment of the university’s first black student, James Meredith, a military veteran with strong academic credentials. Faloon recalled becoming an active participant in the anti-racist movement, involved in preparing anti-racist posters and paintings.After he completed his degree in Fine Arts (Painting) in 1965, Faloon transferred to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

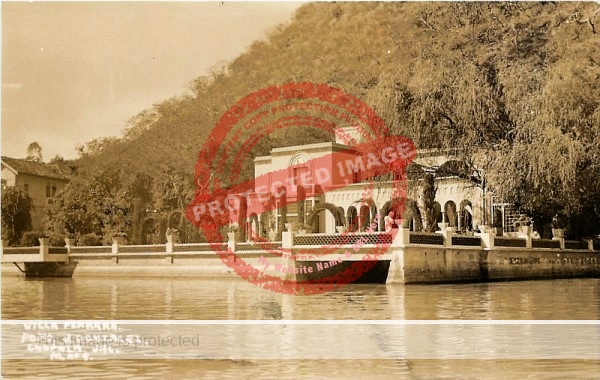

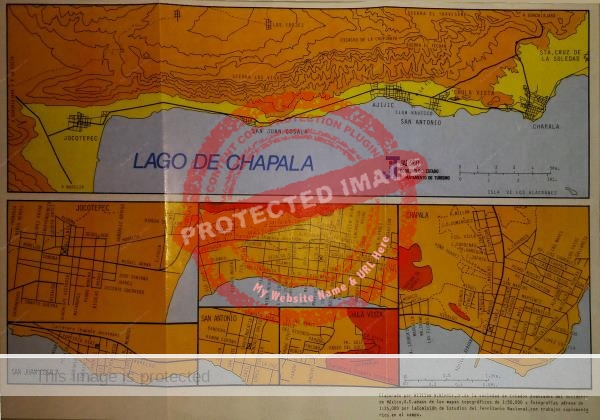

On 30 July 1966, Faloon married Shannon Elizabeth Rodes in Melbourne, Florida. The couple had two young daughters. Faloon began working for his father’s agricultural chemical firm in Clarksville, Mississippi, but soon decided that the environmental impacts of agrochemicals often outweighed their benefits. He and his wife had first visited Ajijic over the winter of 1967/68 and, in 1970, Faloon gave up his position in the family business to live at Lake Chapala full-time, focus on his art and raise his children in a welcoming, friendly, eclectic community.

(l to r): Tom Faloon, Mrs Everett Sherrill, Roy Lichtenstein. 1962. (The Central New Jersey Home News)

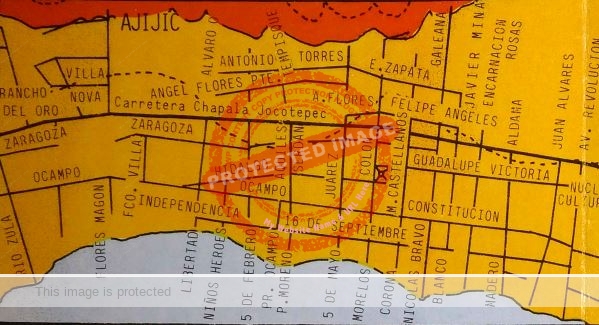

The family lived for a short time at La Villa Apartments (on Javier Mina) in Ajijic before purchasing a home on Donato Guerra. Described as “a serious 28-yr-old artist who studied in New York and Italy”, Tom “comes fully equipped: talent, a stunning Cherokee Indian-Irish wife named Shannon, two girl children and two dogs.” (Guadalajara Reporter, 6 March 1971.)

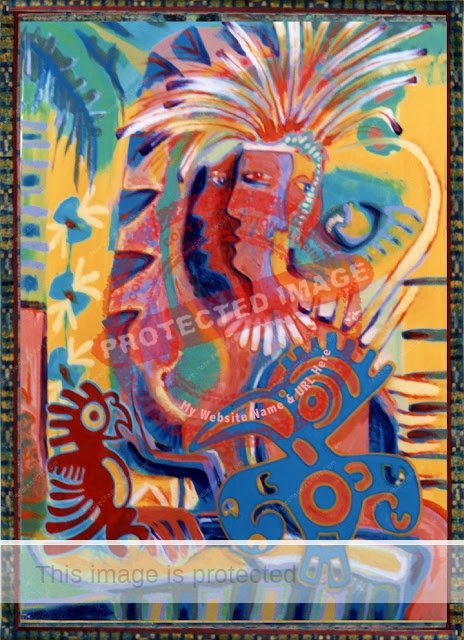

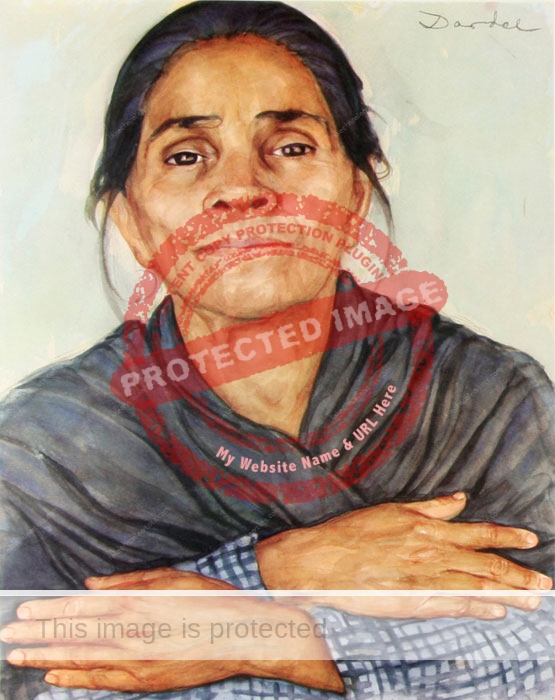

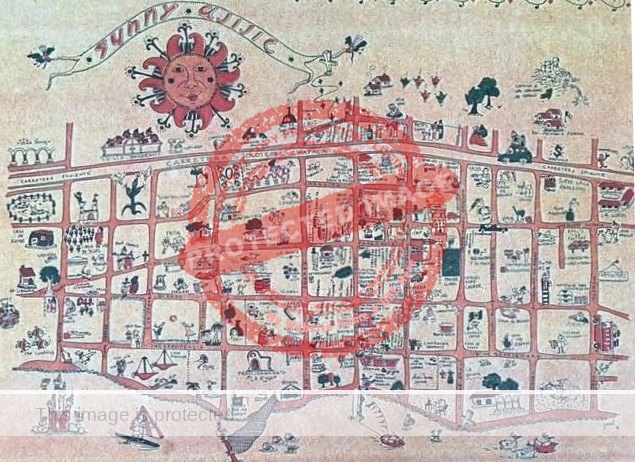

Faloon quickly made friends with his Mexican neighbors and became seamlessly integrated into local life, developing a particular love of Mexican handicrafts, folk traditions and design.

In May 1971, he was one of the large number of artists exhibiting in the “Fiesta of Art” group show held at the residence of Mr and Mrs E. D. Windham (Calle 16 de Septiembre #33). Other artists at that show included Daphne Aluta; Mario Aluta; Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Peter Huf; Eunice (Hunt) Huf; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Gail Michael (Michel); Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; John K. Peterson; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; Robert Snodgrass; and Agustín Velarde.

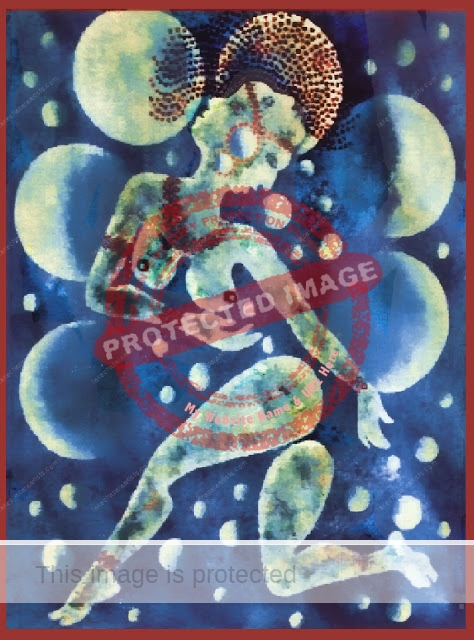

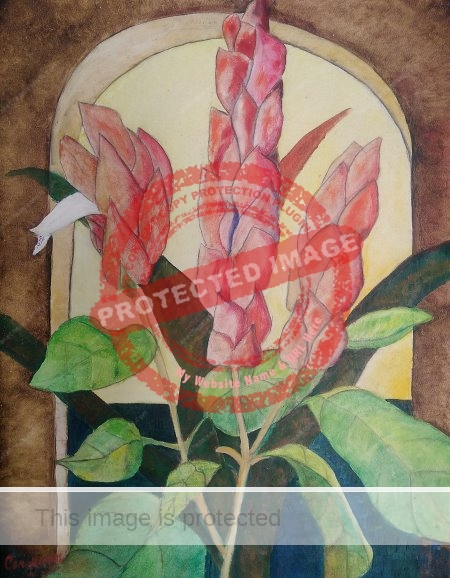

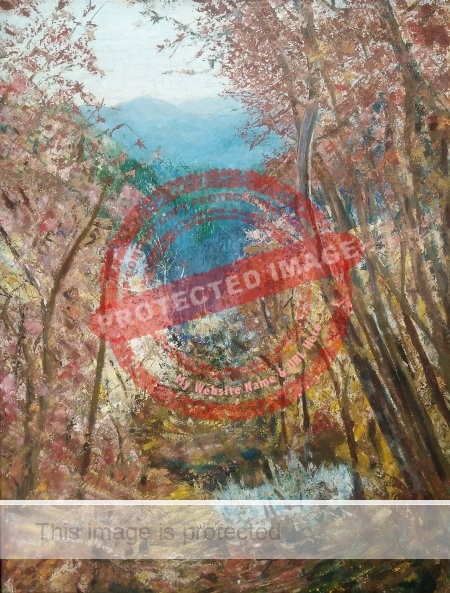

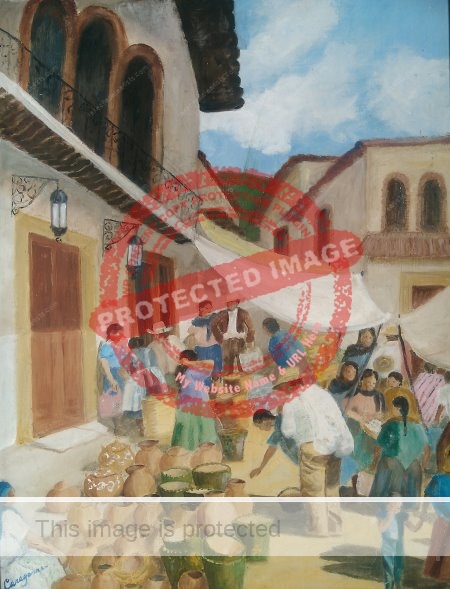

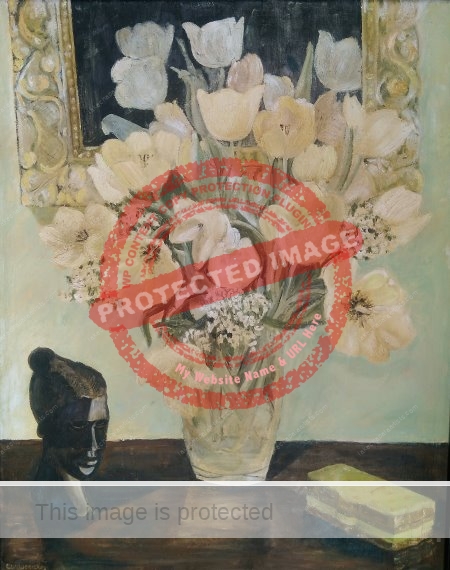

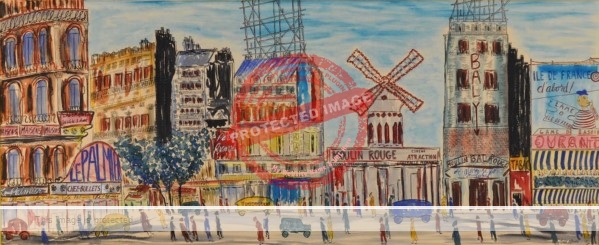

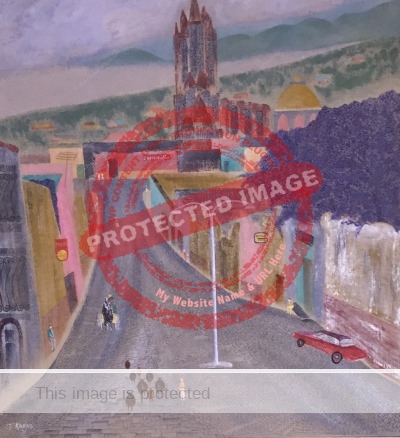

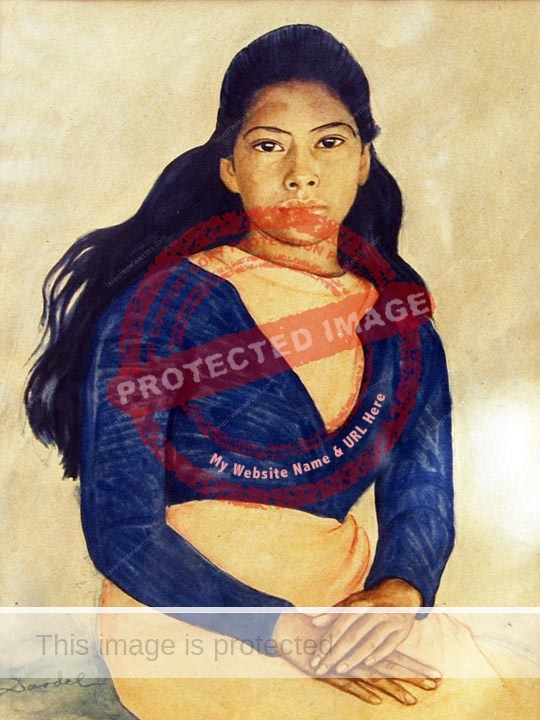

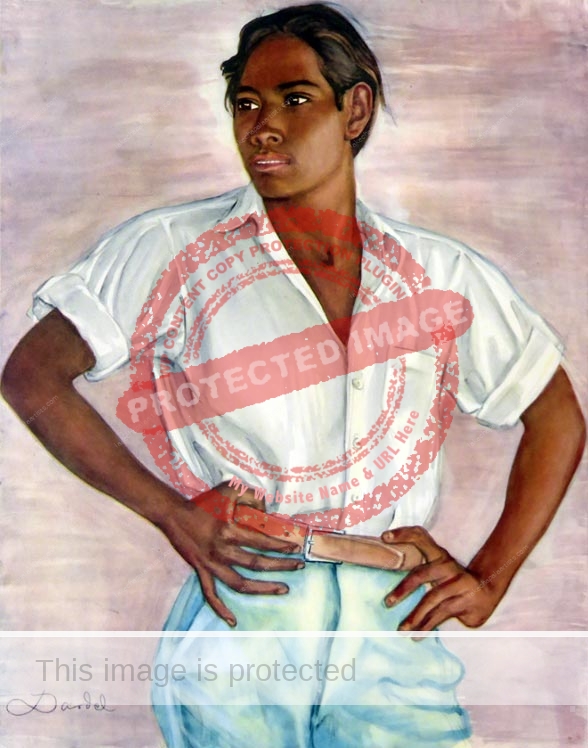

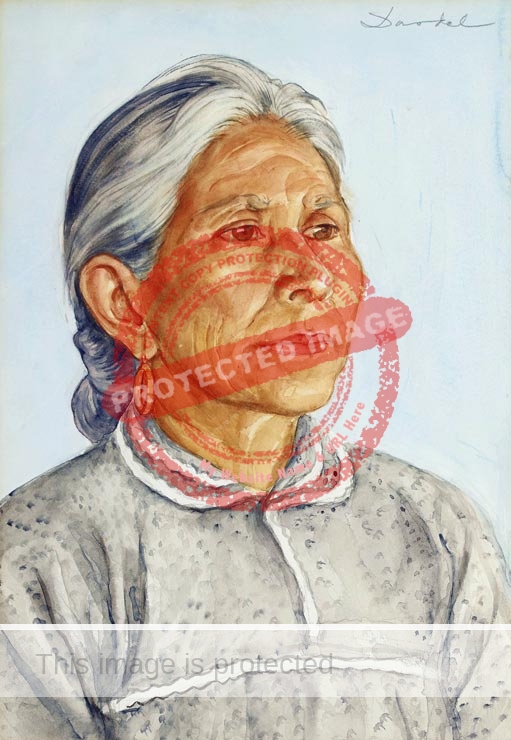

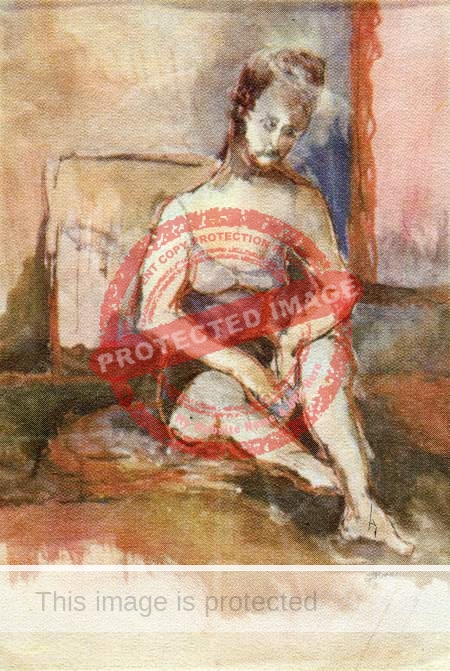

This example of his work was published in A Cookbook with Color Reproductions by Artists from the Galería (1972).

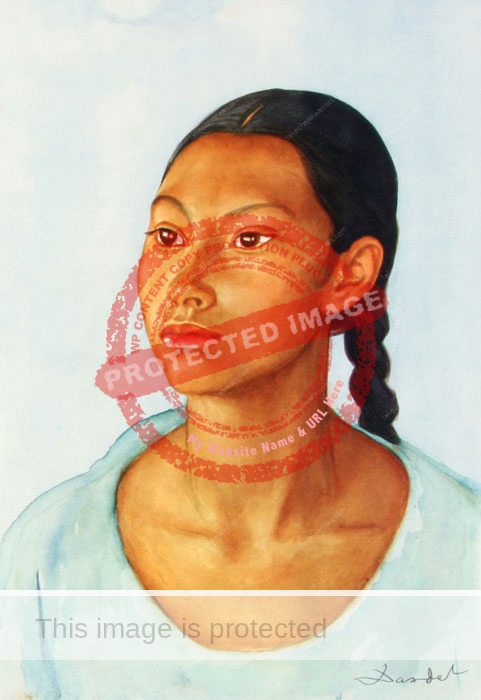

Tom Faloon. ca 1972. “La Mujer”

Tomás, as he was known in Ajijic, remained in the village after he and Shannon separated in 1973. (They divorced in 1979.)

Faloon was an active member of the “Clique Ajijic” which existed for 3 or 4 years in the mid 1970s. This group held exhibitions in Ajijic, Chapala, Guadalajara, Manzanillo and Cuernavaca. The other members of this very talented Mexican Group of Eight were Hubert Harmon, Todd (“Rocky”) Karns, Gail Michel/Michaels, John K. Peterson, Synnove (Shaffer) Pettersen, Adolfo Riestra, and Sidney Schwartzman.

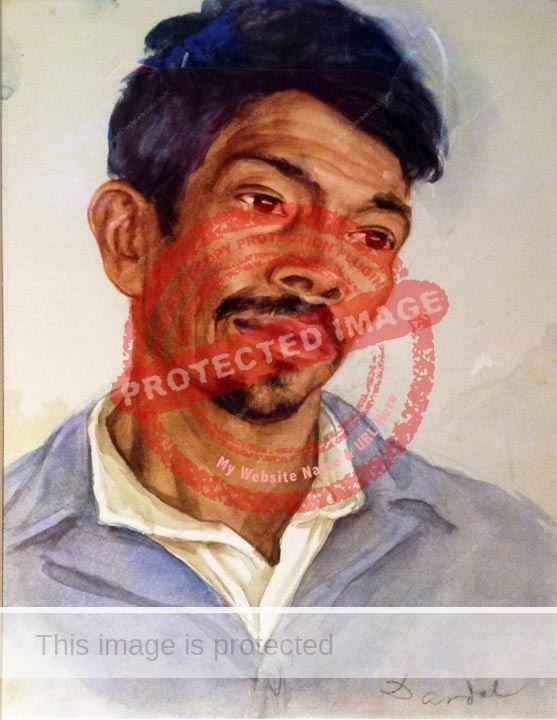

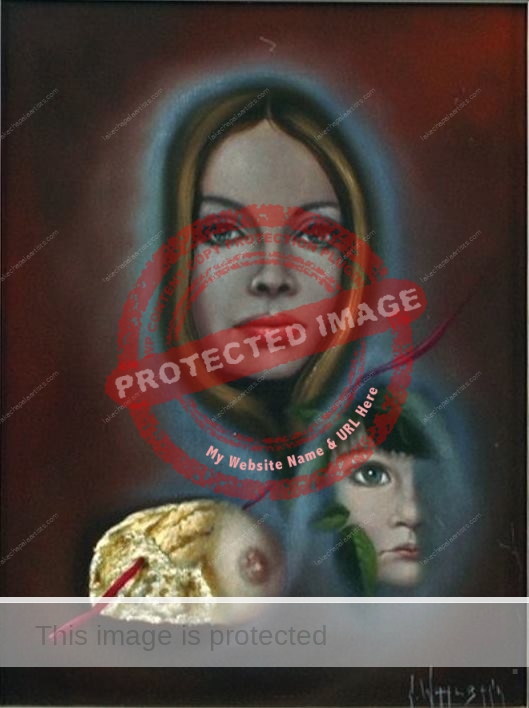

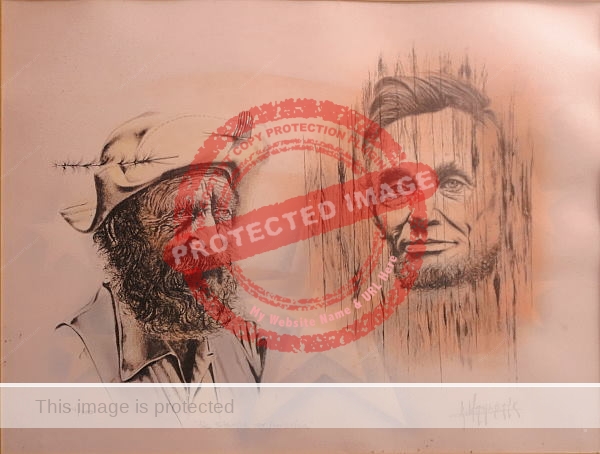

Faloon’s paintings were mostly abstract or impressionist. He participated in several local exhibitions and one of his paintings was purchased for the permanent collection of a museum in Memphis, Tennessee.

Recognizing that art sales might not earn him sufficient income, in the 1980s Faloon began working on remodeling and redesigning traditional village homes. His own artwork took a back seat (though he continued to paint occasionally and complete mixed media works) as he quickly found he was in his element working on homes, undertaking projects that combined his interests in architecture, design and craftsmanship with his love of Mexican materials and handicrafts. Most of the many homes that Faloon lovingly transformed incorporated some whimsical elements: “las locuras de Tomás” as he called them.

Faloon, fluently bilingual, was a generous, kind and sensitive individual, and always willing to help causes close to his heart, including those related to the environment and animal welfare. He was a great supporter of Mexican artisans and their colorful, creative folk art.

Faloon met his soul mate, Carlos Rodriguez Miranda, in the mid-1970s. Their partnership lasted until Faloon’s untimely passing on 5 August 2014 from complications following what should have been a routine surgery in a hospital in Guadalajara.

In her obituary for him, Dale Hoyt Palfrey was absolutely correct to call Tom Faloon an “icon of Ajijic’s expat community” and “one of the community’s most prominent and endearing long-time foreign residents.”

Acknowledgment

My sincere thanks to the late Tom Faloon for his encouragement with this project and for so generously sharing his knowledge and memories of the Ajijic art community with me in February 2014.

Sources

- Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi) 16 April 1965, 44.

- La Galería del Lago de Chapala. 1972. A Cookbook with Color Reproductions by Artists from the Galería. 1972. (Ajijic, Mexico: La Galería del Lago de Chapala).

- Guadalajara Reporter, 6 March 1971.

- Lake Chapala Society, Oral History project: “Tom Faloon” (video).

- Dale Hoyt Palfrey. 2014. “Remembering Tomás Faloon, icon of Ajijic’s expat community”, Guadalajara Reporter, 29 November 2014

- Poughkeepsie Journal (Poughkeepsie, New York) 26 June 1960, 4B.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.