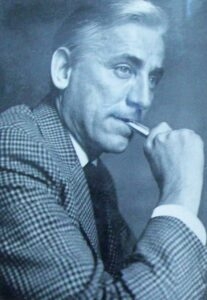

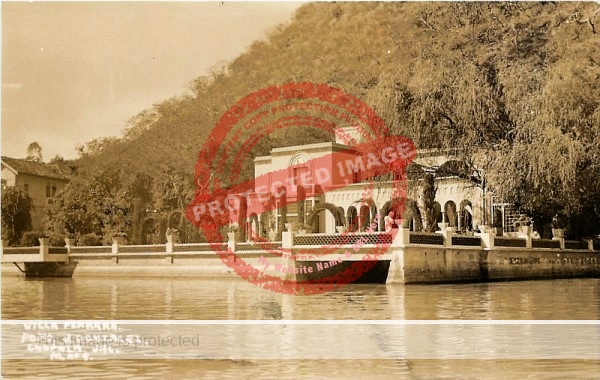

In a previous post, we offered an outline biography of Canadian writer Ross Parmenter, who first visited Mexico in 1946 and subsequently wrote several books related to Mexico.

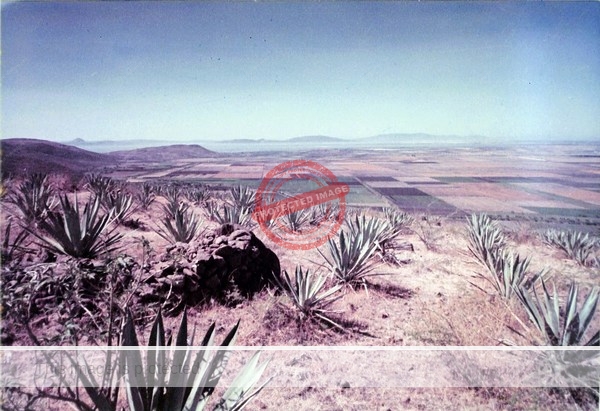

One of these book, Stages in a Journey (1983), includes accounts of two trips from Chapala to Ajijic – the first by car, the second by boat – made on two consecutive days in March 1946. The following extracts come from chapter 3 of Stages in a Journey:

The author was traveling with Miss Thyrza Cohen (“T”), a spirited, retired school teacher who owned “Aggie”, their vehicle. They met up with Miss Nadeyne Montgomery (aka The General), who lived in Guadalajara; Mrs Kay Beyer, who lived in Chapala; and two tourists: Mrs. Lola Kirkland and her traveling companion, Mary Alice Naden.

On 22 March 1946, the party returned to Ajijic, this time by boat, to collect a hat left the day before at Neill James‘ home. They collected the hat, walked around the village, and then returned to the pier to set off back to Chapala. Part way back,

as Colombina rounded a point we saw a little fishing settlement in the bay beyond. We asked the boatman if he could take us near the shore for a closer look. Without a word, he turned the prow towards the land.

Near the water’s edge there were many small willows, with feathery showers of foliage and contorted trunks. Fishing nets, stretched to dry on posts, made diaphanous tents a little way back. A man was standing knee-deep in the water casting a circular net. And as we drew closer we saw other men were drawing water to irrigate the fields.

– – –

The water near the shore was shallow, but the fishermen had created artificial spits of land by setting out stones that made little walls to separate fishing areas. By bringing the bow to one of these the boatman apparently thought it would be possible for the women to cross to land without getting their feet wet. But a rasping sound before we reached the stones showed his miscalculation. But the ladies didn’t mind. Thyrza was in her seventies and Mrs. K. in her fifties, but wading was nothing in their young lives. So off came their shoes and stockings and they paddled to shore.

First we watched the fisherman casting his net. Its outer edges were weighted so that the net spread like a disk as it flew through the air. A cord was attached to the center of the net like the stem to the leaf of a waterlily, and as the disk plopped on the water the man let the cord fall slack. When the net had settled, he started to draw it slowly towards him. The cord pulled the net to a peak and one would have thought he was dragging a sack to the shore.

Once the weights were drawn together to close the bottom of the net, he lifted the whole thing up and emptied a slew of minnows into a round basket.

The tiny fish were silver with eyes like black buttons on disks of bright aluminum. Each fresh lot was lively as it was dumped into the basket. But mass activity soon ceased and then a few would flop a bit and some shivered before lying still.

Because of her fondness for fish, T was particularly fascinated by the minnows. Having seen their counterparts dried and piled on fibre mats in the market of Chapala, she asked the fisherman what they were called.

Her question, being in English, was incomprehensible to him. But I could help, because trying to find out about other things had led me to learn that nombre was the word for name..

“El nombre?” I asked, pointing to the minnows.

“Charales,” the man replied.

One of the reasons T liked our hotel in Chapala so well was because every lunch and dinner it served delicious pescado blanco. The fish were always cooked the same way, presenting a similar flat appearance with the structural outlines obscured by the batter in which they were fried a delicate brown. Having the attention of a man who knew something about the fish of the lake, she asked him if he had any pescado blanco.

He understood and went over to some moist sacking. Lifting back a flap, he exposed some small, but plump fish of conventional shape. T was surprised. Not realizing the hotel split them open to cook them, she had expected a sort of flounder.

. . . [When the engine failed] I looked back on the shore. Being a short way out, we could see a wider stretch than when we had been right on the land. In addition to the people we had seen close up — the fisherman throwing his net, the woman cooking and the men working the hoist — we could see others on either side. At one little point there were women on their knees washing clothes. In the age-old grace of their activity, they were beautifully grouped and the bright garments they had laundered were lying around drying ¡n the sun. Near the women were brown children playing on a narrow beach and dashing calf-deep into the water from time to time. Further along some fishermen were pushing out one of their high-peaked canoas to fish where the water was deeper.

The animals were picturesque too. At the mouth of the inlet a chestnut horse and a gray burro were drinking, their muzzles almost touching. Different species though they were, they suggested a father and son. A black and white cow had waded right into the water to do her drinking. A few small ducks swam near her, tame as could be. On the shore a piglet rooted around near the woman with the charcoal fire. Some puppies frisked about and chickens were pecking.

Source:

- Ross Parmenter. 1983. Stages in a Journey. New York: Profile Press.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).