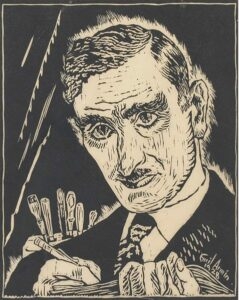

We know disappointingly little about the life and work of artist Emanuel(e) Mario Aluta. Aluta moved to Ajijic with his second wife Daphne Greer Aluta (born 1919) in about 1969. The couple had filed for divorce in 1965, and the divorce was made final in October 1970, after their move to Mexico. It is unclear whether or not Mario remained in Ajijic after 1974 when Daphne married Colin MacDougall in a small ceremony at the home of Sherm and Adele Harris, the then managers of the Posada Ajijic.

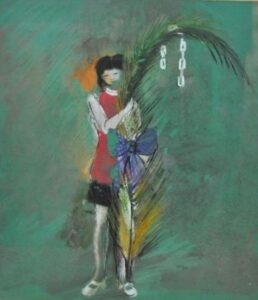

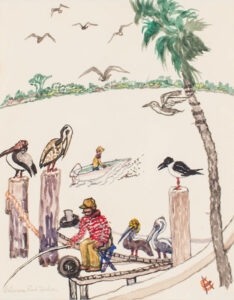

Mario Aluta’s artwork, described in a review by Hannah Tompkins as a “series of male figures … vigorously painted with strong emphasis on planal design,” was included in a 1970 exhibition at the Casa de la Cultura Jalisciense in Guadalajara. The show opened on 6 June 1970 and featured a long list of Lakeside and Guadalajara artists. Among the other Lakeside artists in the show were Daphne Aluta, Peter Huf and his wife Eunice Hunt, John Frost, Bruce Sherratt and Lesley Jervis Maddock (aka Lesley Sherratt).

Both Mario and Daphne Aluta also showed work in the “Fiesta de Arte” in May 1971 at the home of Frances and Ned Windham at Calle 16 de Septiembre #33 in Ajijic. More than 20 artists took part in that event, including Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; Tom Faloon; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Peter Huf; Eunice (Hunt) Huf; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Gail Michael (Michel); Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; John K. Peterson; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; Robert Snodgrass; and Agustín Velarde.

Emanuel(e) Mario Aluta was born in Constantinople, Turkey, on 3 January 1904, but (also?) had Italian citizenship. He died in California on 22 September 1985.

I know nothing about Aluta’s early life, education or art training, but believe his first wife was Charlotte Maria Richter, who was born in Vienna, Austria, in about 1911. The couple seem to have first entered the U.S. in about 1936. In November 1937, they are recorded as crossing the border from Mexico back into the U.S.. The following year (1938) they applied to become naturalized U.S. citizens. Their application was finally approved in August 1943.

At the time of the 1940 U.S. Census, the couple was living in Los Angeles. According to the census entry, they had been living in Nice, France, five years earlier in 1935.

Mario Aluta was 56 years of age when he married 41-year-old Daphne Greer in Clark County, Nevada on 25 May 1960. The couple made their home in Santa Barbara, California, where Mario worked in real estate with Fyfe & Boyd. Both Mario and Daphne attended Adult Education Fine Arts classes, and Mario’s three submissions for Santa Barbara’s Third Annual Adult Education Fine Arts and Craft Show in 1966 were all awarded honorable mentions. Mario’s work was first included in the annual juried show of the Santa Barbara Art Association in 1969.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.