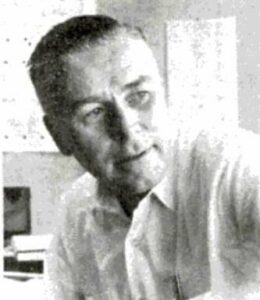

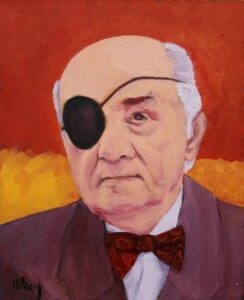

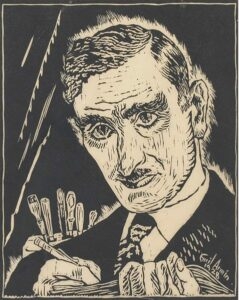

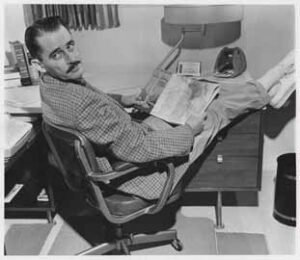

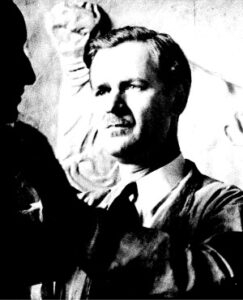

The distinguished Canadian poet Earle Alfred Birney (1904–1995) traveled in Mexico in the 1950s and wrote several poems based on his experiences, including one entitled “Ajijíċ”.

Birney was born in Calgary, Alberta, on Friday 13 May 1904 and raised on a farm near Creston in British Columbia. After short stints working on a farm, in a bank and as a park ranger, he attended university to study chemical engineering.

Birney was born in Calgary, Alberta, on Friday 13 May 1904 and raised on a farm near Creston in British Columbia. After short stints working on a farm, in a bank and as a park ranger, he attended university to study chemical engineering.

By the time he graduated, his academic interests had changed. Birney graduated with a degree in English from the University of British Columbia (1926). He also later studied at the University of Toronto (1926-27); University of California, Berkeley (1927); and at the University of London in the U.K. (1934).

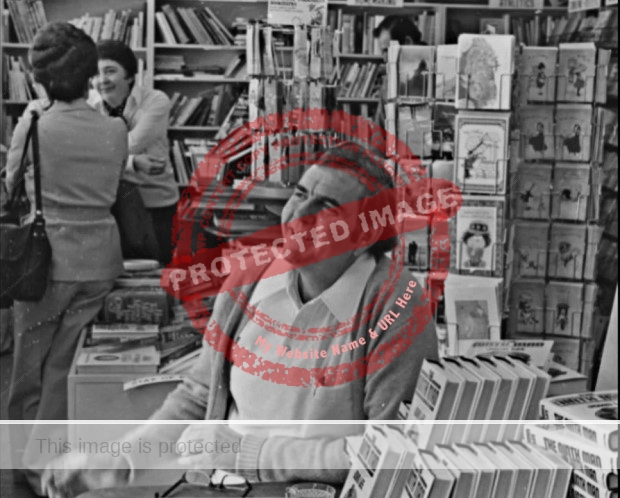

During the second world war, he was a personnel officer in the Canadian Army, the basis for his 1949 novel Turvey, which won the Leacock medal for humor in 1950. Immediately after the war, Birney took a post at the University of British Columbia, where he was instrumental in founding and directing Canada’s first creative writing program. He retired from that university in 1965 to become the first Writer in Residence at the University of Toronto.

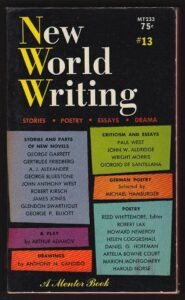

His poetry was widely acclaimed, published in more than hundred journals and regularly featured in anthologies. It also resulted in him becoming a two-time recipient of the Governor General’s Award, Canada’s top literary honor. Birney also wrote plays, novels and non-fiction, as well as working at different times as literary editor of Canadian Forum, editor of Canadian Poetry Magazine and supervisor of European foreign-language broadcasts for CBC.

Birney died of a heart attack on 3 September 1995 at the age of 91.

Birney’s poem “Ajijíċ” [sic] is one of a series of 12 Mexican poems that forms the second section of his Ice Cod Bell or Stone: A Collection of New Poems (1962). The other poems are entitled: “State of Sonora”, “Sinaloa”, “Njarit”, “Late Afternoon in Manzanillo”, “Irapuato”, “Pachucan Miners”, “Six-Sided Square: Actopan”, “Francisco Tresguerras”, “Beldams of Tepoztlán”, “Conducted Ritual: San Juan de Ulúa”, and “Sestina for Tehauntepec”. The place names in the titles clearly shows that Birney traveled quite widely during his time in Mexico, from Sonora and Sinaloa in the north to San Juan de Ulúa in Veracruz and Tehuantepec in the southern state of Oaxaca.

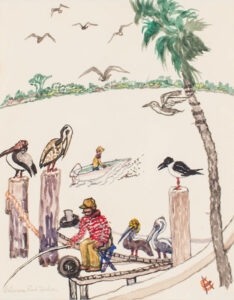

In Ajijíċ, Birney describes a “hip gringo” who, while enjoying a morning tequila, brings out “from under the bar”, “his six feet of representational nonart.”

The poem’s final section includes a description of sundown when,

“Outside the fishermen will pass /

and the blobs of pescada blanca in the nets /

swaying over their shoulders will flake /

their bare shanks with mica as they trudge” …

[Note that the correct Spanish spelling for Lake Chapala’s whitefish is pescado blanco.]

Birney’s Mexican poems were very favorably reviewed by other noted Canadian poets and literary figures. A.J.M. Smith, in his “A Unified Personality – Birney’s Poems”, praised this “brilliant series of Mexican poems. I don’t know where you’ll find anything better in modern North American poetry than the combination of wit and sentiment, pertinent observation and auricular, almost ventriloquistic precision than “Sinaloa”, “Ajijic”, or “Six-Sided Square: Actopan”.”

Mexican literary analysis of Birney’s poetry has been more critical. For instance, Claudia Lucotti, an academic at UNAM (Mexico’s National University), argues that Earle Birney describes a Mexico of cliches, a simplistic country, one seen only through tourist eyes. She regards Birney’s attempt to record the typical speech patterns of a Mexican speaking English as patronizing and stereotypical. Incidentally, in the same chapter, which examines how various Canadian poets have looked at Mexico, Lucotti considers the same to be true for Al Purdy, another Canadian poet associated with Lake Chapala.

Birney’s poetry collections include David and Other Poems (1942), Now Is Time (1945), The Strait of Anian (1948), Trial of a City and Other Verse (1952), Ice Cod Bell or Stone (1962), Near False Creek Mouth (1964), Memory No Servant (1968), pnomes jukollages & other stunzas (1969), Rag & Bone Shop (1970), what’s so big about GREEN? (1973), Alphabeings and Other Seasyours (1976), The Rugging and the Moving Times (1976), Copernican Fix (1985) and Last Makings: Poems (1991).

Birney’s fiction works include Turvey: a military picaresque (1949), Down the Long Table (1955) and Big Bird in the Bush: Selected stories and sketches (1978), while his non-fiction writing includes The Creative Writer (1966), The Cow Jumped Over the Moon: The writing and reading of poetry (1972), and Essays on Chaucerian Irony (1985).

Sources / references

- Wailan Low. Undated. Earle Birney : Biography (formerly at http://canpoetry.library.utoronto.ca/birney/).

- Claudia Lucotti. 2000. “Nosotros en los otros: visiones de México en la literatura canadiense contemporánea de lengua inglesa,” in Canadá un estado posmoderno, coordinated by Teresa Gutiérrez-Haces (Plaza y Valdes, 2000).

- A.J. M. Smith. 1966. “A Unified Personality: Birney’s Poems,” in Canadian Literature. (Vancouver, British Columbia, 1966), 30, 4-13

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.