Explanations of why the famous British author D. H. Lawrence chose to visit Chapala in 1923 often ignore the key role played by Idella Purnell, a strong-willed young poetry fanatic from Guadalajara.

Purnell had studied under American poet Witter Bynner at the University of California, and Bynner had received an open invitation to visit Purnell and her family in Guadalajara. Over the winter of 1922-23, Bynner and Lawrence had become friends during the English author’s first stay in New Mexico.

In 1923, Lawrence was becoming restless and proposed a trip to Mexico. Lawrence and his wife Frieda invited Bynner, and Bynner’s secretary-companion Willard “Spud” Johnson (who had been a fellow student of Purnell in Bynner’s class), to accompany them. After a short time in Mexico City, the group settled in Chapala for the summer, during which time they met frequently with Idella Purnell and her dentist father, Dr. George Purnell, sometimes in Guadalajara, sometimes in Chapala. The Purnells had numerous links to Chapala and Ajijic (where Dr. Purnell owned a small house), and Idella Purnell went on to enjoy considerable success as a poet, editor, and author of children’s books.

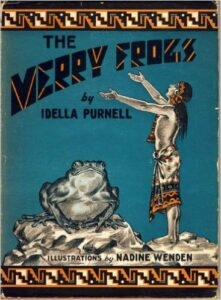

Idella Purnell: The Merry Frogs (1936)

[Born on 28 March 1863, Purnell’s father, George Edward Purnell (1863-1961), was among the earliest graduates in dentistry from the University of Maryland, the first dental college in the U.S. Purnell practiced in Missouri before moving to California. In 1889, during a downturn in the Californian economy, a vacation trip to Mexico became a permanent move.

Purnell set up a dental practice in Guadalajara and got married. Dr. Purnell also had mining interests, including a stake in the Quien Sabe Mining company at Ajijic, where several rich veins of gold ore were found in 1909, duly reported in the Los Angeles Herald and El Paso Herald. Some years later (1930), Purnell was kidnapped by bandits but released unharmed after less than a week in exchange for four hundred pesos.]

Idella, the eldest of the Purnell’s three children, was born in Guadalajara on 1 April 1901, and named after her mother. As a teenager, she taught primary school in Guadalajara before attending the University of California, Berkeley. During her second semester there, she was the youngest student in a poetry class given by Witter Bynner. She also became an associate editor of The Occident, the university’s literary magazine.

After she gained her B.A. degree in 1922, Purnell returned to Guadalajara where she worked as a secretary in the American Consulate for the next couple of years. She began writing to Bynner, asking him to come for a visit:

“I was very hungry for intellectual contacts; Guadalajara at that time was an arid desert.” (letter to Nehls)

Taking advantage of her connections to the Berkeley poetry circles, Purnell spent much of 1922 planning the first issue of Palms, a small poetry magazine that she would edit and publish until 1930.

The first issue of Palms appeared in the spring of 1923, just before her prayers for further intellectual stimulation were answered by the visit of Bynner, Johnson and Lawrence. Bynner had been supportive of Palms from the start, but had certainly not anticipated Lawrence’s willingness to offer some poems and drawings, in exchange for some home-made marmalade.

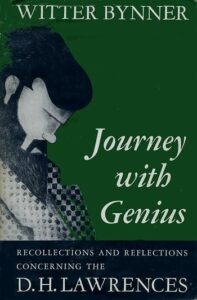

In Journey with Genius, his account of visiting Mexico with Lawrence, Bynner describes how they visited the Purnells’ “quaint little untidy house of adobe”:

“Never have I seen Lorenzo [Lawrence] more amiable, more ingratiating that he was that evening. He listened to poems of Idella’s and to some of her Palms material. He was full of saintly deference to everyone…” (Journey with Genius, 82).

Idella Purnell was initially taken aback by Lawrence, but soon became enthralled:

“Even warned about the red beard, it was with a sense of shock that I met Mr. Lawrence, so thin, so fragile and nervous-quick, and with such a flaming red beard, and such intense, sparkling, large mischievous blue eyes which he sometimes narrowed in a cat-like manner. His rusty hair was always in disorder, as though it never knew a comb. But otherwise the man seemed neat almost to obsession and frail, as though all his energy went into producing the unruly mop on top and the energetic still beard.” [Letter from Purnell to Bynner, quoted in Journey with Genius]

Over the next few months, the Purnells saw Lawrence regularly, either at their home in Guadalajara, or in Chapala at weekends when they stayed Saturday nights at the Hotel Arzapalo.

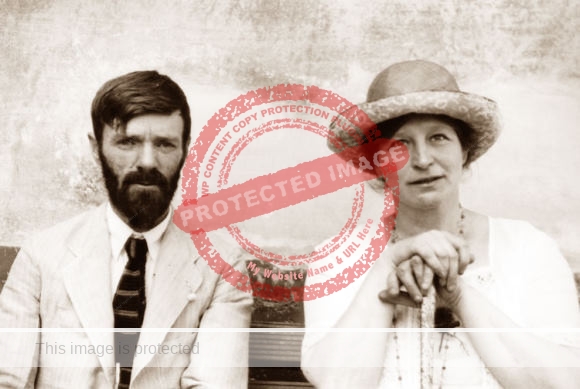

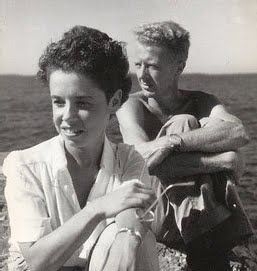

Idella Purnell, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Willard Johnson, Dr George E. Purnell at a cantina in Chapala, 1923. Photo: Witter Bynner.

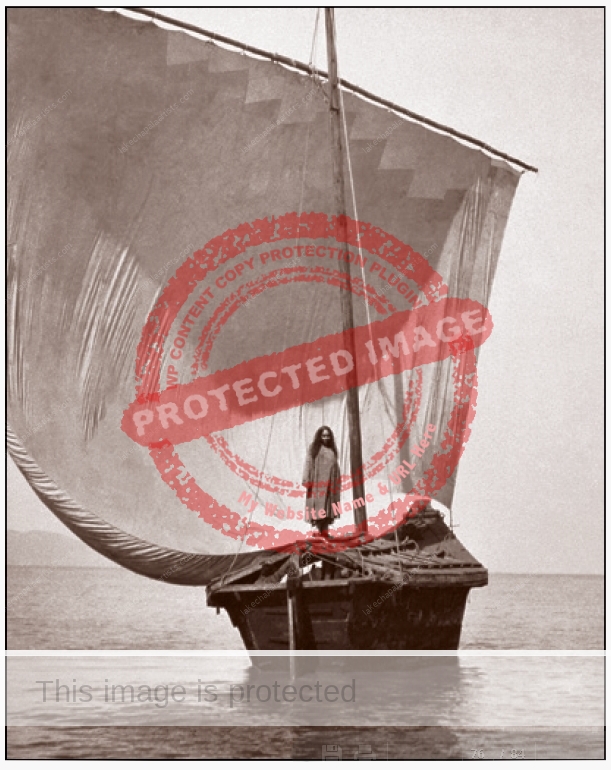

In early July, a few days before the Lawrences left Chapala, they arranged an extended four‑day boat trip around the lake with Idella Purnell and her father. The group left Chapala aboard the Esmeralda on 4 July.

The Esmeralda boat trip, 1923. Photo credit: Willard Johnson.

The boat ran into very bad weather overnight, causing several of the group to be sick, before they finally limped into shore on the south side of the lake near Tuxcueca. From there, Idella took a badly-suffering Bynner back to Chapala on the regular steamer. While friends accompanied Bynner to a hospital in Guadalajara, Idella remained in Chapala to greet the remaining members of the party when they finally returned a few days later.

Based on these times with Lawrence and his friends in Chapala, Purnell wrote an unpublished roman à clef novel entitled Friction. The novel, whose title was suggested by Lawrence, apparently incorporates some excellent descriptions of the local area, and revolves around a political assassination. Among the characters are Edmund (Lawrence), Gertrude (Frieda), Judith (Idella), Lionel (Johnson) and Dean (Bynner).

Purnell continued to publish and edit Palms, considered a forum for young, upcoming poets, until 1930. She never published any of her own poems in Palms, but under her leadership, the magazine published work by more than 350 poets, many of them rising stars at the time, even if largely forgotten since.

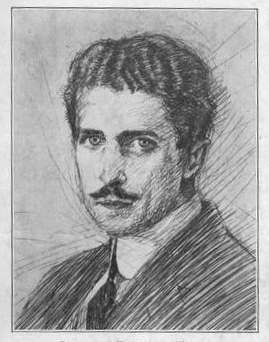

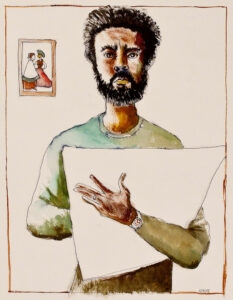

Palms included contributions from Bynner, D.H. Lawrence, Johnson, Marjorie Allen Seifert, Warren Gilbert, Mable Dodge Luhan, Countee Cullen, Norman Maclean, Carl Rakosi, Langston Hughes and Alexander Laing, among others. Both Lawrence, and his Danish artist friend Kai Gøtzsche (1886‑1963) (see image) provided illustrations for Palms‘ covers, as did Idella’s younger sister Frances-Lee Purnell. Famous American poet and critic Ezra Pound, in his essay “Small Magazines” (1930), said that Palms “was probably the best poetry magazine of its time”, high praise indeed.

Palms included contributions from Bynner, D.H. Lawrence, Johnson, Marjorie Allen Seifert, Warren Gilbert, Mable Dodge Luhan, Countee Cullen, Norman Maclean, Carl Rakosi, Langston Hughes and Alexander Laing, among others. Both Lawrence, and his Danish artist friend Kai Gøtzsche (1886‑1963) (see image) provided illustrations for Palms‘ covers, as did Idella’s younger sister Frances-Lee Purnell. Famous American poet and critic Ezra Pound, in his essay “Small Magazines” (1930), said that Palms “was probably the best poetry magazine of its time”, high praise indeed.

During the second half of the 1920s, Purnell yo-yoed between Mexico and the U.S. In summer 1925, she was head of the foreign book department at the Los Angeles Public Library, where she first met future husband, John M. Weatherwax, before moving back to Mexico in October.

[In 1926, while staying at the Hotel Cosmopolita in Guadalajara, Emma Lindsay Squier (1892-1941) became good friends with the Purnells. Squier’s time with them is described in detail in her memoir Gringa (1934).]

In 1927, Purnell and Weatherwax married, and she joined him in Aberdeen, Washington. She returned to Guadalajara the following year to have their only child, a daughter who, tragically, died as an infant. Weatherwax sued for divorce in 1929, but despite this, he and Purnell collaborated on 19 books between June 1929 and October 1930.

In 1927, Purnell and Weatherwax married, and she joined him in Aberdeen, Washington. She returned to Guadalajara the following year to have their only child, a daughter who, tragically, died as an infant. Weatherwax sued for divorce in 1929, but despite this, he and Purnell collaborated on 19 books between June 1929 and October 1930.

She gave up publishing Palms in 1930. The title was briefly revived by Elmer Nicholas in 1932, a minister in Frankton, Indiana.

On a business trip to New York in 1930, Purnell fell in love with Remington (“Remi”) Stone. The couple lived in New York and married in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, on 30 September 1932.

In 1931, Purnell returned once again to Guadalajara, and the following year was the organizer and dean of the first University of Guadalajara summer session. Many years later, in 1975, her photograph appeared in the Guadalajara Colony Reporter as a guest of honor at ceremonies marking the 50th anniversary of the founding of the University of Guadalajara, since she had been the University of California’s delegate to the university’s opening in 1925.

In 1932, Purnell applied, unsuccessfully, for a Guggenheim fellowship to study the anthropology of Lake Chapala and write an anthropological-fictional novel to be called Canoa, which she hoped “would convey to the reader the idyllic atmosphere of the Mexican countryside.” (Delpar)

Purnell had two children with Remington Stone: Marijane Stone, born in 1934, and Remington, born in 1938. The couple also later brought up Purnell’s niece, Carrie Stone. In 1935, when Marijane was only 14 months old, the family began another Mexican gold-mining venture. Remi remained in New York to secure financing, while Idella and Marijane joined Dr. Purnell in Ameca, Jalisco, to oversee the mining operations. All three became ill, so Remi arrived to help run the mine. In 1937, Idella and Marijane went to Los Angeles for medical reasons. Remi gave up the mine shortly afterwards when the Mexican government began expropriating foreign-owned mining property.

In Los Angeles, Idella taught creative writing, and during World War II, she became a riveter for Douglas Aviation and Fletcher Aviation.

In the 1950s, she started studying dianetics, and opened a Center for Dianetics in Pasadena in 1951, before moving it to Sierra Madre in 1956.

Purnell died in Los Angeles, California, on 1 December 1982; she had played an active role in many different literary and educational achievements of the twentieth century. Her archive of correspondence and papers, 1922‑1960, is held by the University of Texas.

In her long literary career, Idella Purnell (Stone) was the author or co-author of numerous children’s books, including The Talking Bird, an Aztec Story Book: Tales Told to Little Paco By His Grandfather (1930); Why the Bee is Busy and Other Rumanian Fairy Tales Told to Little Marcu By Baba Maritza (1930); Little Yusuf: The Story of a Syrian Boy (1931); The Wishing Owl, a Maya Storybook (1931); The Lost Princess of Yucatan (1931); The Forbidden City (1932); Pedro the Potter (1935); The Merry Frogs (1936).

In her long literary career, Idella Purnell (Stone) was the author or co-author of numerous children’s books, including The Talking Bird, an Aztec Story Book: Tales Told to Little Paco By His Grandfather (1930); Why the Bee is Busy and Other Rumanian Fairy Tales Told to Little Marcu By Baba Maritza (1930); Little Yusuf: The Story of a Syrian Boy (1931); The Wishing Owl, a Maya Storybook (1931); The Lost Princess of Yucatan (1931); The Forbidden City (1932); Pedro the Potter (1935); The Merry Frogs (1936).

However, Purnell’s best known work is the Walt Disney version of Bambi (1944), when she “retold” Felix Salten’s original version, Bambi, A Life in the Woods, with Disney providing the illustrations. (Incidentally, Walt Disney himself actually visited Chapala at least once; he gave a speech at the Villa Montecarlo in October 1964, during a “De Pueblo a Pueblo” meeting attended by Mexican president Adolfo Lopez Mateos and US military historian John D Eisenhower).

In addition to children’s stories, Purnell also wrote non-fiction, including a Spanish language biography of the famous American botanist Luther Burbank: Luther Burbank, el Mago de las Plantas (Argentina: Espasa Calpe, 1955), and 30 Mexican Menus in Spanish and English (Ward Ritchie Press, 1971).

In addition to children’s stories, Purnell also wrote non-fiction, including a Spanish language biography of the famous American botanist Luther Burbank: Luther Burbank, el Mago de las Plantas (Argentina: Espasa Calpe, 1955), and 30 Mexican Menus in Spanish and English (Ward Ritchie Press, 1971).

Works compiled and edited by Purnell include 14 Great Tales of ESP (Fawcet, 1969) and Never in This World, a collection of stories by twelve famous science-fiction writers, including Isaac Asimov (Fawcett, 1971).

Her short pieces include “The Turquoise Horse”, a legend set at Lake Chapala, first published in the Los Angeles Times on 27 December 1925, and “The Idols Of San Juan Cosala“, originally published in American Junior Red Cross News in December 1936.

Sources:

- Witter Bynner. 1951. Journey with Genius (New York: John Day)

- Helen Delpar. 1995. The Enormous Vogue of Things Mexican: Cultural Relations Between the United States and Mexico, 1920-1935 (University of Alabama Press)

- David Ellis. 1998. D. H. Lawrence: Dying Game 1922-1930; The Cambridge Biography of D. H. Lawrence, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press.

- D. H. Lawrence. 1926. The Plumed Serpent.

- Frieda Lawrence (Frieda von Richthofen). 1934. Not I, But the Wind… (New York: Viking Press)

- Harry T. Moore and Warren Roberts. 1966. D. H. Lawrence and his world. (London: Thames & Hudson)

- Edward Nehls (ed). 1958. D. H. Lawrence: A Composite Biography. Volume Two, 1919-1925. (University of Wisconsin Press).

- Vilma Potter. 1994. “Idella Purnell’s PALMS and Godfather Witter Bynner.” American Periodicals, Vol 4 (1994), pp 47-64, published by Ohio State University.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Young attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor from 1957-1960 and was co-editor of Generation, the campus literary magazine. In 1961 he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, and proceeded to have a variety of jobs (folksinger, laboratory aide, disk jockey, medical photographer, clerk typist, employment counselor) before eventually completing an honors degree in Spanish at University of California, Berkeley, in 1969. In 1963, Young married Arline Belck, a freelance artist; the couple’s son, Michael James, was born in 1971.

Young attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor from 1957-1960 and was co-editor of Generation, the campus literary magazine. In 1961 he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, and proceeded to have a variety of jobs (folksinger, laboratory aide, disk jockey, medical photographer, clerk typist, employment counselor) before eventually completing an honors degree in Spanish at University of California, Berkeley, in 1969. In 1963, Young married Arline Belck, a freelance artist; the couple’s son, Michael James, was born in 1971.

![l to r: Robert Hunt, Galdys Ficke, Arthur Ficke, ca 1935. [Source: Kraft: "Who is Witter Bynner"?]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/hunt-robert-with-fickes-chapala-1934-5s.jpg)