Newspaper correspondent and intrepid traveler Fanny H. Ward (née Brigham) was born in Monroe, Michigan, on 27 January 1843 and died in Kent, Ohio, on 4 October 1913. Little is known about her early education and upbringing. She married in 1862 and moved to Washington DC about a decade later. The couple had three children, the youngest of which accompanied her on some of her later long-distance travels.

Ward had begun writing for newspapers, including the Cleveland Leader and the Portage County Republican-Democrat, in the 1870s and in 1884, now divorced, traveled for the first time to Mexico and Central America where she explored and wrote travel and lifestyle pieces for the next two and a half years. During that time, she climbed Mt Popocatepetl, the volcano overlooking Mexico City, contracted yellow fever and crossed the Andes on muleback.

A few years later Ward visited Guatemala and British Honduras (now Belize) before continuing south to Chile, Argentina, the Falkland Islands, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela. In 1898, Ward visited Cuba on humanitarian missions with her good friend Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, and in the following year she spent time in Europe. By that time more than 40 newspapers were publishing her work. Ward’s writing career came to an abrupt end in 1905 after a stroke left her blind in one eye.

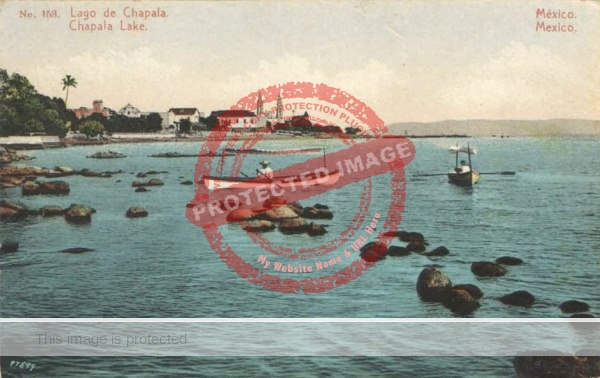

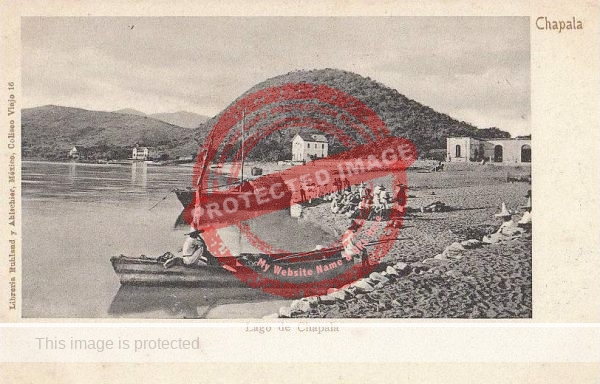

Among the articles written by Ward that relate to Mexico is a report of a three-day horse ride to Chapala, titled “Picnicking in Mexico: An Excursion to Lake Chapala,” published in April 1887.

Mrs Fannie Ward. 1887. Picnicking in Mexico.

Day 1 – Riding towards the lake

A Día de Campo (“day in the country”) as a Mexican picnic is called, is a favorite amusement here, especially in the vicinity of any body of water… We were invited to join an excursion to Lake Chapala, forty miles distant from Guadalajara—a “picnic” which occupied three days spent mostly on horseback.

…

Our party of eighteen started from Guadalajara in the twilight of an early morning, eating breakfast and lunch from well filled hampers al fresco by the wayside, and arriving in good time for six o’clock dinner at the hacienda of Señor Alzuyeta, ten miles this side of the lake.

I have failed to find any record of an influential family named Alzuyeta in Jalisco at the time, and it is unclear which hacienda is being referred to, though it may have been Atequiza. The hacienda is described as:

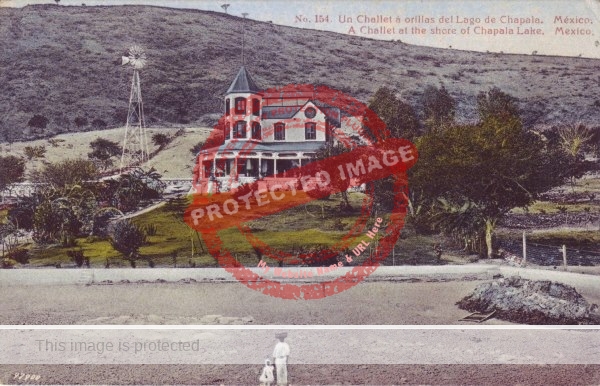

unique in its way, with little furniture (like all Mexican country houses) but what there is being very handsome, most of it having been brought from Spain nearly two centuries ago by a titled ancestor. The dining hall—a noble room, capable of seating thee hundred persons, opens into a garden which is kept in beautiful order, with fine trees, clear tanks, sparkling fountains and a profusion of roses of extraordinary beauty even in this land of flowers… the fountains tiled around in Moorish style, ornamented with Chinese figures and enormous China vases of great value.”

Day 2 – Visit to Lake Chapala

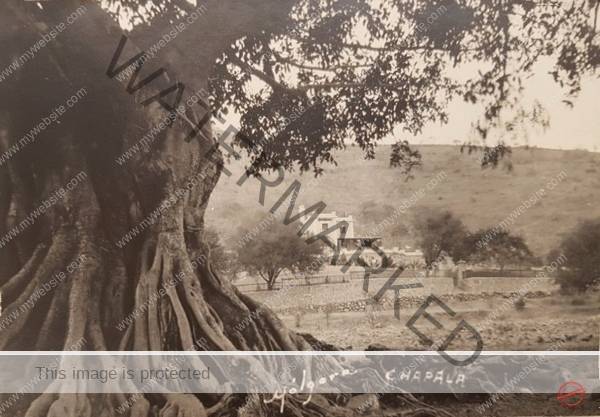

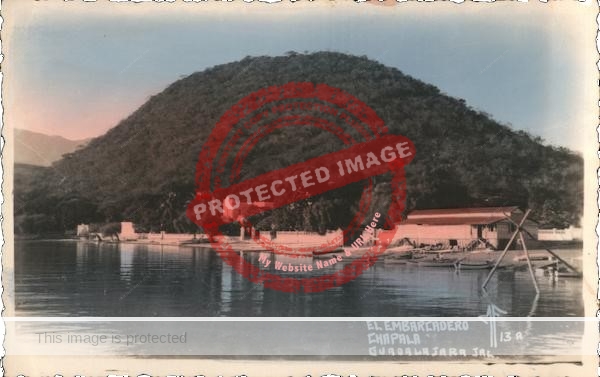

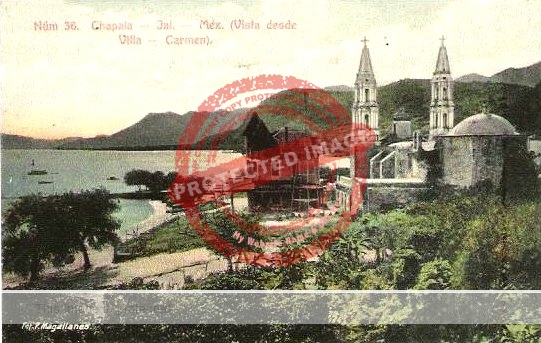

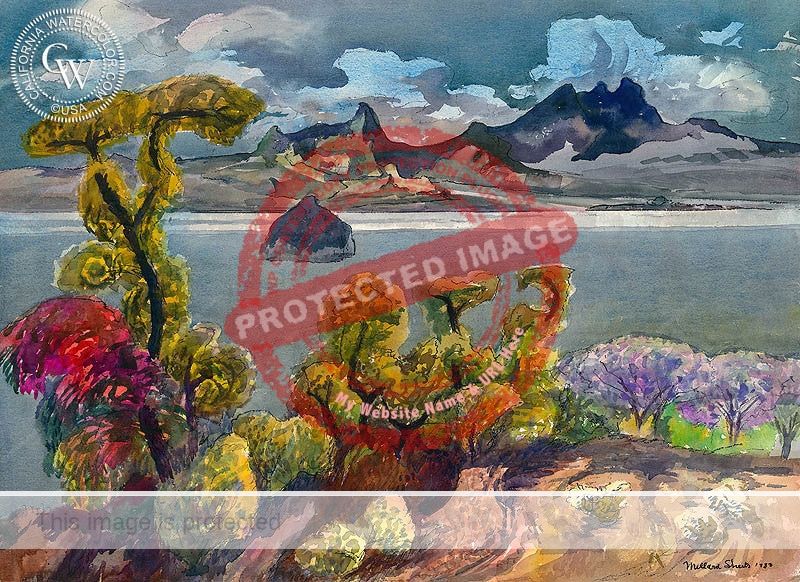

The next morning they left the hacienda early for Chapala, where they “spent a long day upon its peaceful waters and among its many islands.”

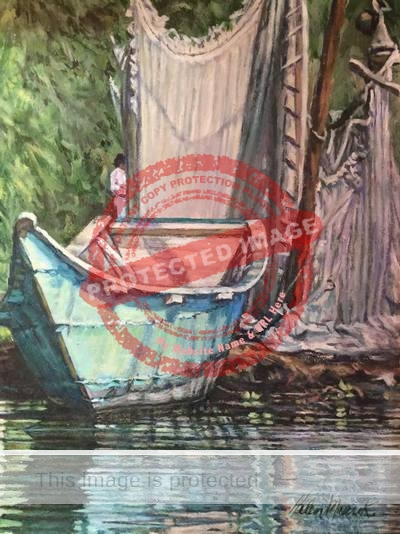

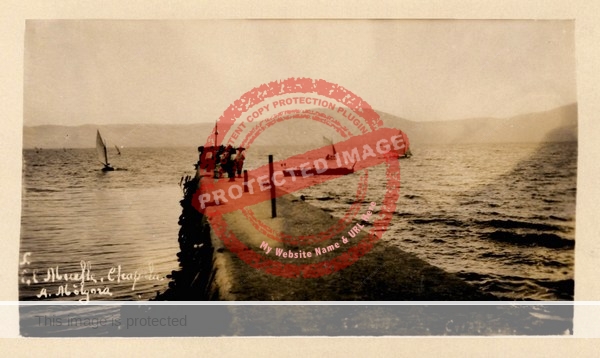

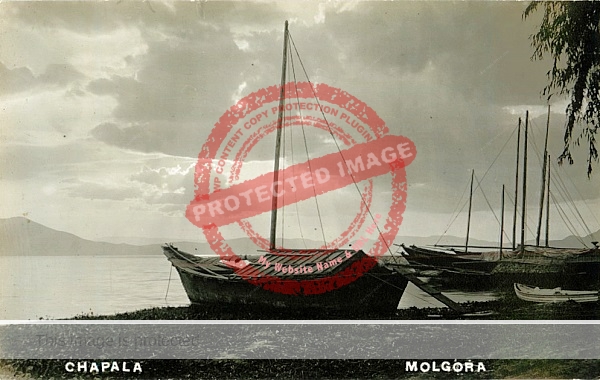

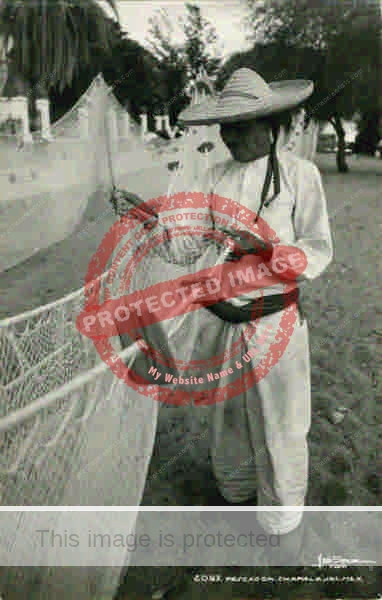

A small steamboat makes a daily tour of Lake Chapala, stopping at various points of interest; and everywhere along its shores Indian boatmen may be hired to paddle you about in canoes, dug-outs and rafts. Some of the latter have benches and awnings—much like those on the Vija canal, near the City of Mexico—and each barge, with three bare-legged boatmen to propel it, will easily carry a dozen people.

In the lake are many islands, upon one or two of which extensive ruins have been found. Some of the islands are absolutely unexplorable, on account of the innumerable number and variety of serpents that infest them, and appear to be entirely given over to these reptiles. No wonder those early Indians considered a skirt of woven snakes the most appropriate garment for the goddess of the earth!”

…

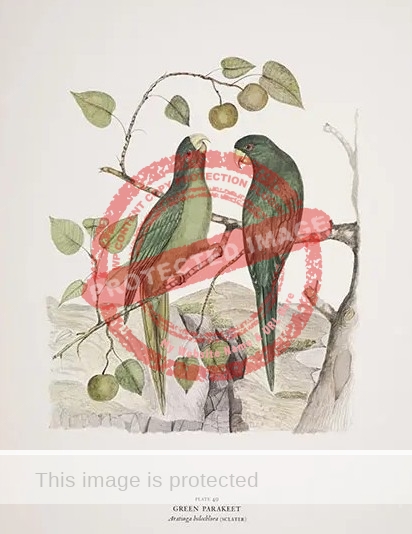

In attempting to explore some of the islands of Lake Chapala it seemed as if the earth literally wore ‘a skirt of serpents.’ The ground seemed alive with them, swaying and writhing from every bush, hissing and squirming on every fallen tree and rippling the water in all directions. It was a question as to which was most numerous, the birds above or snakes below. Among the islands are numerous shoals which barely project their pebbly heads above the water. These shoals are inhabited by millions of terns, gulls and other water fowl, and when approached the birds rise up in swarms, darkening the air, uttering deafening cries and darting about the intruder in a threatening manner…. the scene on the shoals, after the birds have deserted them, is most astonishing. Gulls and terns make no nests, and do not even take pains to hollow out a place in the gravel; but to every pebble there seems to be a dozen eggs.”

According to Ward, the annual spring hatching of birds’ eggs led to a frenzy of snakes below and hawks above.

The group returned to the hacienda in time for a late dinner, comprised of mole, boiled nopales, fried bananas, green chili in various sauces, frijoles, tortillas, cured goat’s milk cheese and guava jelly.

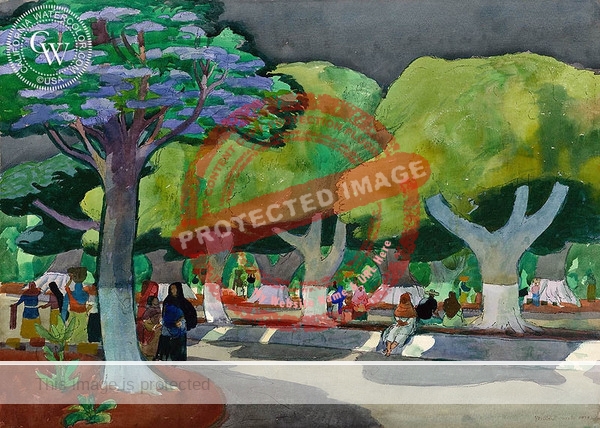

Both evenings at the hacienda we were sumptuously entertained by music, dancing and feasting, all the good people of the vicinage having been invited to meet us. The orange trees in the patio, beneath which the feast was spread, were hung with Chinese lanterns and the farther grounds illuminated with blazing torches of fir…. One evening we played at juegos de prendas—games with forfeits—which was made very amusing by the lively imagination of the ladies in inventing punishments for their caballeros.”

The following day, they rode back to Guadalajara.

Fannie Ward was just one of several pioneering female travelers who made important contributions to travel writing in the nineteenth century. Among the other early female travelers who wrote important accounts of Lake Chapala are Rose Georgina Kingsley; (Selina) Maud Pauncefote; Frances Christine Fisher (aka Christian Reid); and Mrs Alec Tweedie.

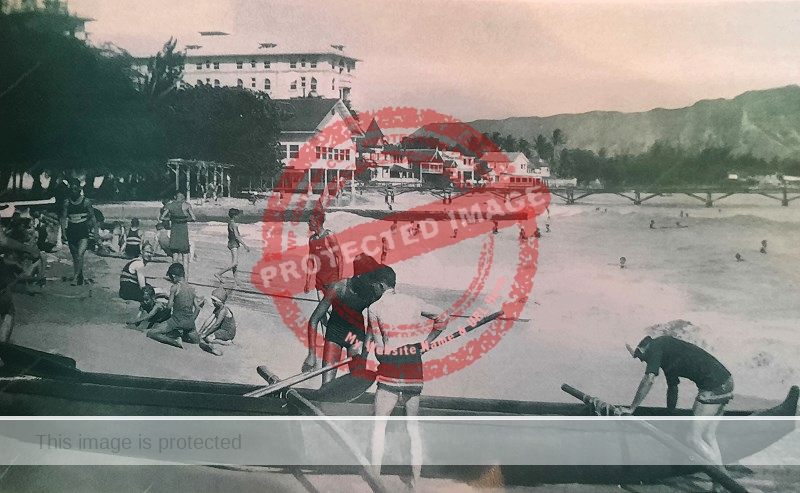

My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources

- Roger J. Di Paolo. 2013. “Portage Pathways: Globe-trotting Fannie B. Ward came home to Ravenna.” Record-Courier, 6 Oct 2013.

- El Informador: 3 Dec 1944, 11; 16 Dec 1944, 16; 24 Jan 1947, 6.

- Fannie B Ward. 1886. ““The Scorpions of Mexico.” The Newnan Herald (Georgia), 19 October, 1.

- Fannie B Ward. 1884. “Monterrey—the Metropolis of Northern Mexico.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, March 1884.

- Fannie B Ward. 1887. “How the “Old, Old Story” Is Told in Mexico. Love-making and Marriage among the Aristocracy of Spanish-America.” The Cambridge Press, Volume XXI, Number 48, 19 February 1887.

- Fannie B Ward. 1887. “In Southern Mexico. Picnicking at Lake Chapala.” The Sacramento Union, 30 April 1887, 4.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.

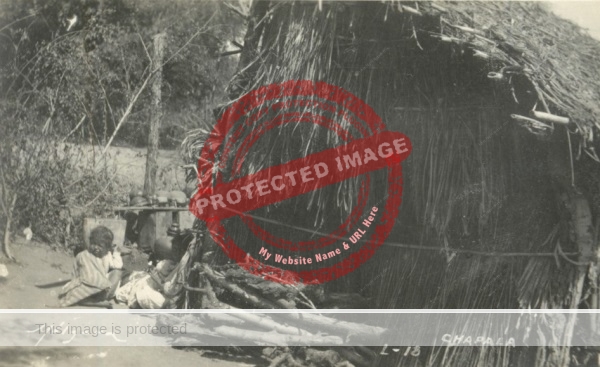

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

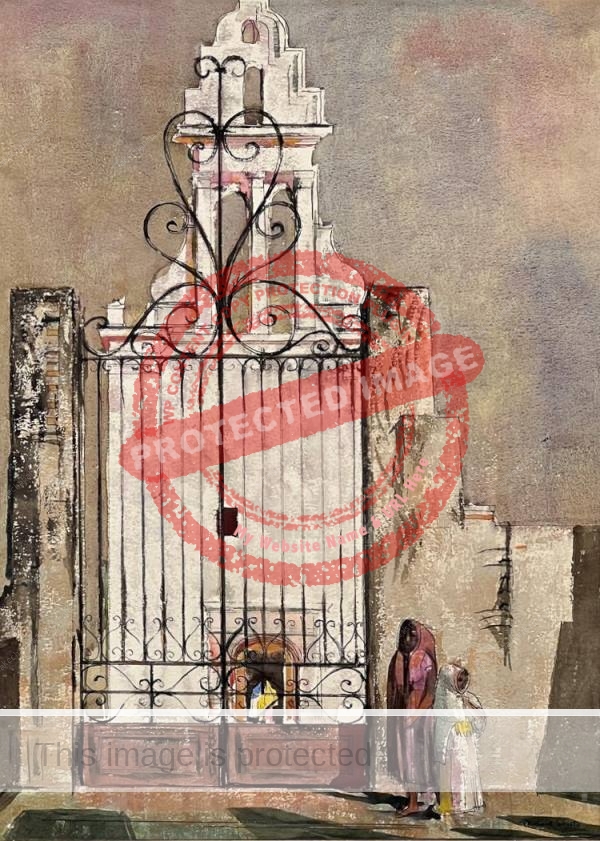

Its publication was timed to coincide with the designation of the City of Chapala as a “Ciudad Señorial e Insigne” (Stately and Distinguished City). The book has contributions by various writers and historians on a wide range of topics, from the early (precolonial) history and evangelization, to the events on Mezcala Island during the fight for independence, as well as details of the lives and contributions of certain key individuals to projects that established Chapala’s enduring appeal.

Its publication was timed to coincide with the designation of the City of Chapala as a “Ciudad Señorial e Insigne” (Stately and Distinguished City). The book has contributions by various writers and historians on a wide range of topics, from the early (precolonial) history and evangelization, to the events on Mezcala Island during the fight for independence, as well as details of the lives and contributions of certain key individuals to projects that established Chapala’s enduring appeal.