After visiting Ajijic in the mid-1940s, Irma René Koen spent the remaining three decades of her life living and painting in Mexico.

Koen, whose birth name was Irma Julia Köhn, was born in Rock Island, Illinois, on 8 October 1883. She graduated from Rock Island High School before briefly attending Augustana College. Despite being an accomplished cellist, she opted to enroll at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in 1903; she was a regular exhibitor in its exhibitions from 1907 to 1917.

Koen completed her studies at the Woodstock School of Landscape Painting, and also studied under C. F. Brown, W.L. Lathrop and John Johansen in Vermont before taking a trip to Europe in 1914, where she was studying with Henry B. Snell at St. Ives in England when the first world war erupted. Koen returned to the US After the war, Koen painted in southern France and North Africa.

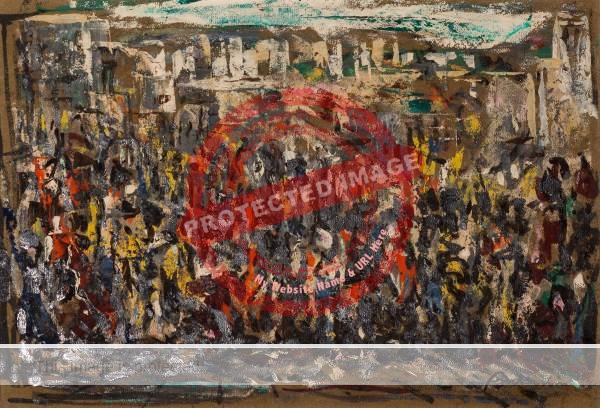

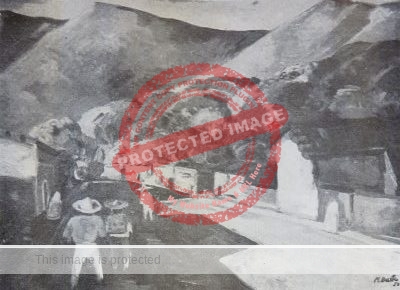

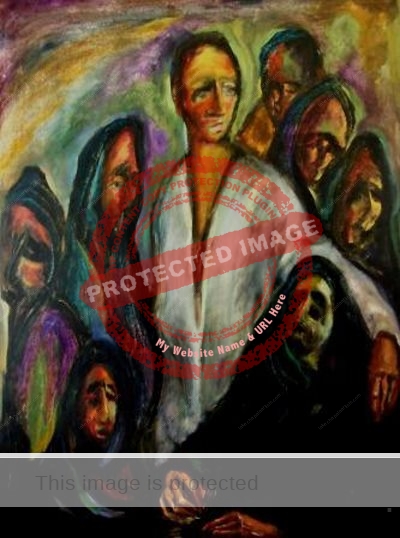

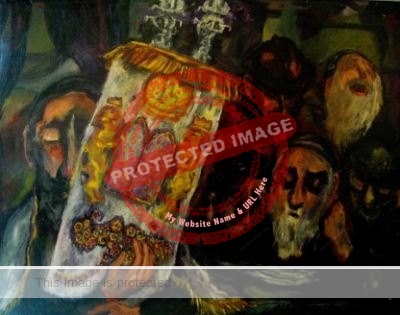

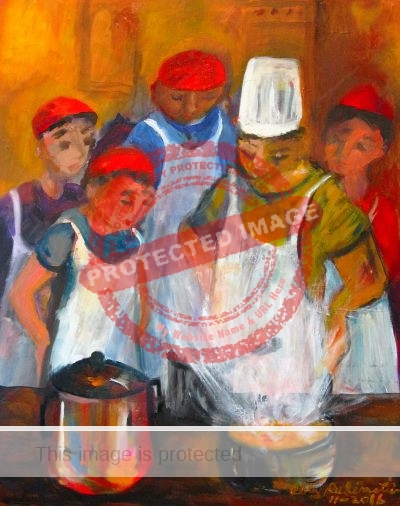

Market scene in Central America painted by Irma Koen

Koen, who never married, traveled very widely during her working life, studying and painting in numerous art colonies, including St. Ives, Cornwall, England (1914); Monterey/Carmel, California (1915); East Gloucester, Massachusetts (1917); New Hope, Pennsylvania (1928); Boothbay Harbor, Maine (1927, 1928); Taos, New Mexico (1929). She also visited Asia, including Nepal. Prior to 1923, she signed her paintings as “Irma Köhn.” Sometime after a trip to France and North Africa in 1923-24, she changed her professional name to “Irma René Koen”.

She was already an artist of considerable renown before visiting Mexico. For example, the Christian Science Monitor noted in 1927 that Koen was “often designated as America’s leading woman artist.”

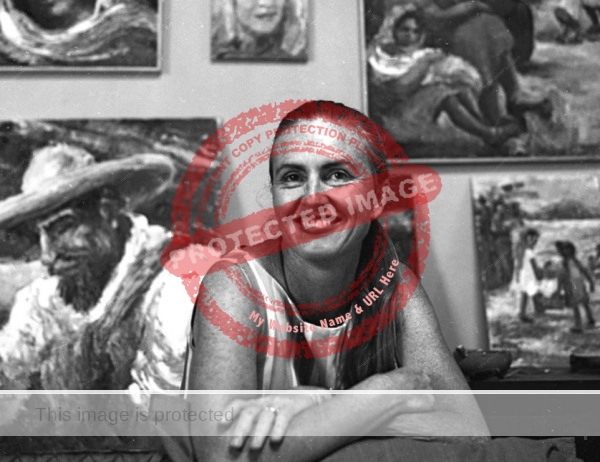

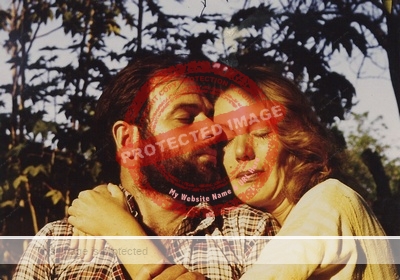

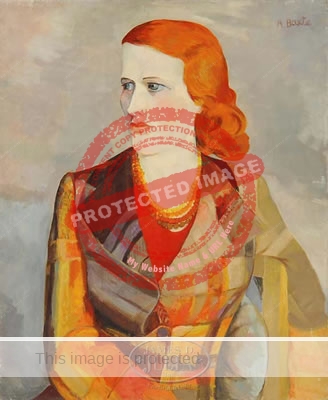

Photo of Koen from “The News,” Mexico D.F. , 1956

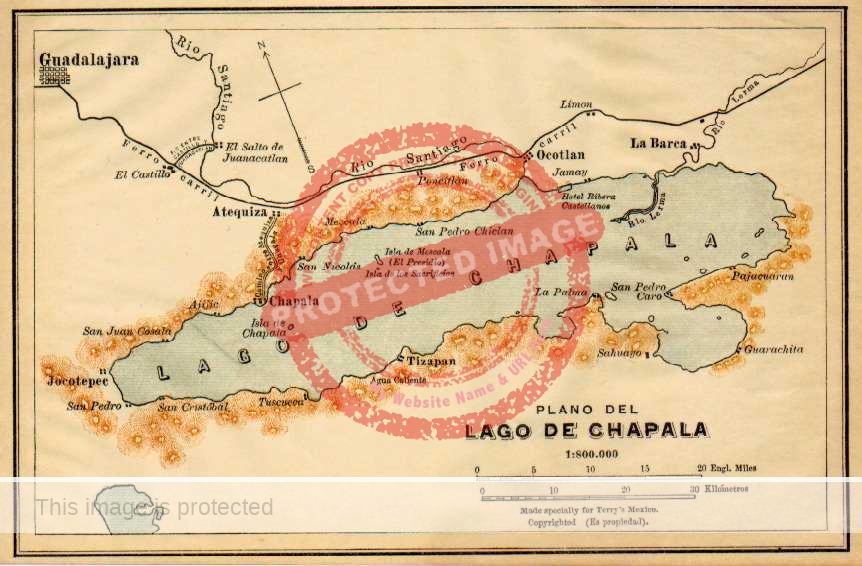

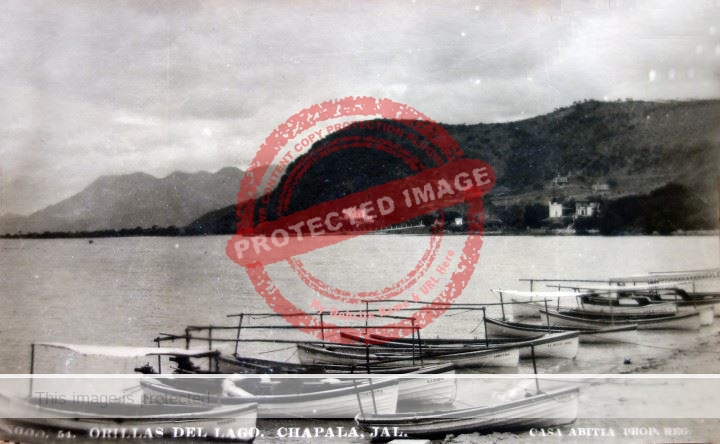

After the second world war, she spent the remainder of her life based in Mexico. Art historian and biographer Cynthia Wiedemann Empen writes that Koen traveled to Mexico in the early 1940s for two months, moved to San Miguel de Allende circa 1944, and resided briefly in Ajijic on Lake Chapala, Pátzcuaro and Mazatlán before establishing a permanent home and studio in Cuernavaca, in the central Mexican state of Morelos, near Mexico City.

Neill James, writing about Ajijic in 1945, described how a recent visitor “Irma René Koen, an impressionist painter from Chicago, found a rich source of material in the local landscape”, so presumably Koen most likely visited Ajijic in late 1944 or early in 1945.

A “Mrs Sam Shloss” of Des Moines visited Ajijic a few years later. Interviewed on her return home in February 1949, she reported how she had visited Neill James in “primitive Ajijic” and purchased “a blouse of Indian handiwork” from James’ small shop. Schloss claimed that the blouse had been designed by “Irma Rene Koen, whose work will be exhibited in March at the Des Moines Art Center” and that the blouses were “marketed by Miss James in an attempt to help the native Mexican women earn pesos with their embroidery.” (Sylvia Fein, the famous American surrealist artist who lived for several years in Ajijic in the mid-1940s, also contributed designs to Neill James, and helped market the blouses in Mexico City and beyond.)

According to a report in 1946 in The Dispatch, an Illinois daily, Koen had already spent two and a half years in Mexico, having spent “the first summer” in “the Indian village of Ajijic which is a mecca for artists and writers.” The report quoted Koen as explaining how she generally “stayed from 3 to 5 months in a town and then moved on.” At that time, Koen relied on her memory and impressions to complete all her paintings in her studio, having found that “painting on the scene was impossible as the natives would practically mob artists who attempted it.”

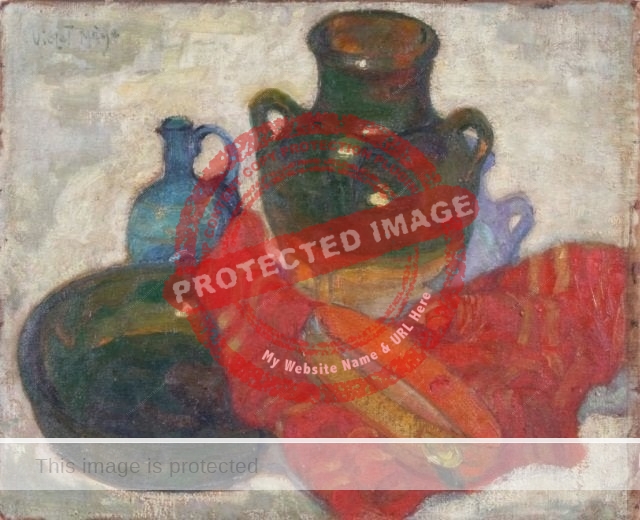

Her first major exhibition in Mexico was held in 1947 at the Circulo de Bellas Artes de México; this exhibit, of (25 oils and 18 watercolors) was later shown in Chicago. The following year, art critic Guillermo Rivas extolled the virtues of Koen for readers of Mexican Life, describing how her painting had “changed completely” since arriving in Mexico: “Her image of Mexico is that of people and landscape fused within a rhythmic movement of incandescent color…. Putting aside her brushes she works with a palette-knife, arranging her undiluted pigments over the canvas in heavy strokes…. It is very seldom indeed that a foreign painter working in Mexico does not yield to its influence and there are occasions when such influence is sufficiently powerful as to define a turning point in their creative course.”

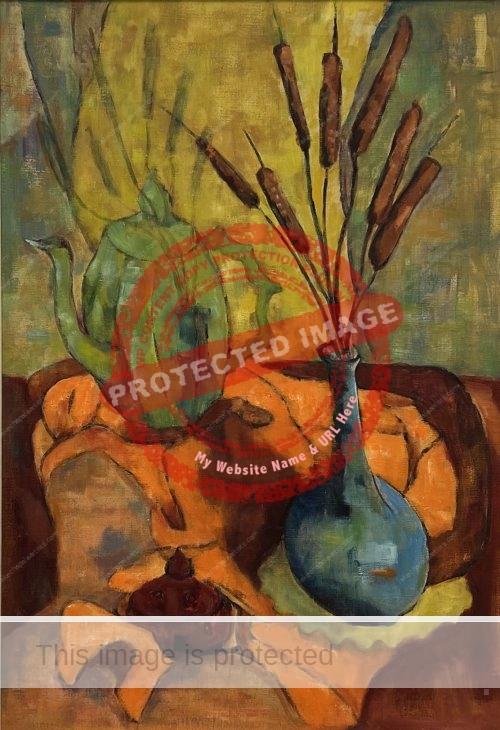

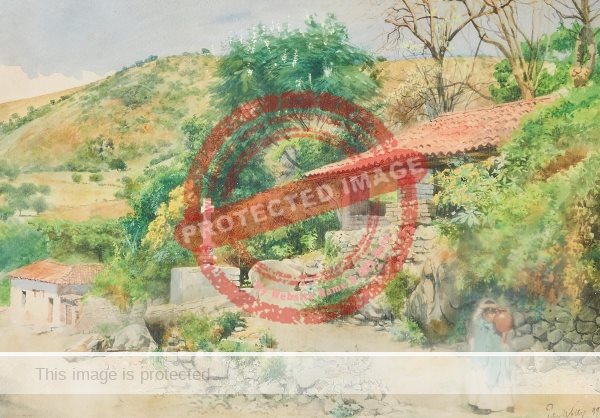

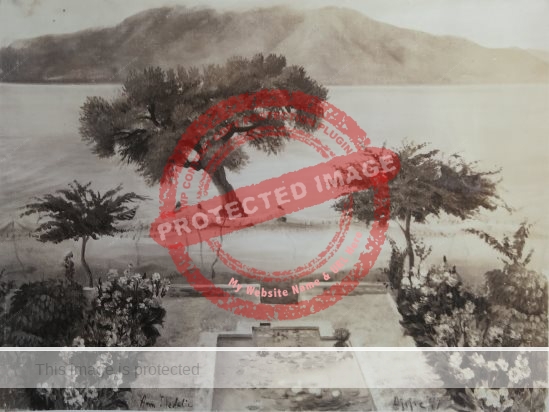

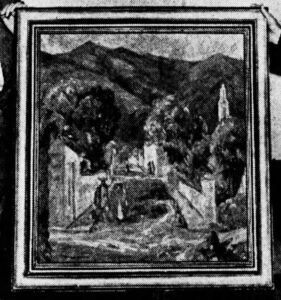

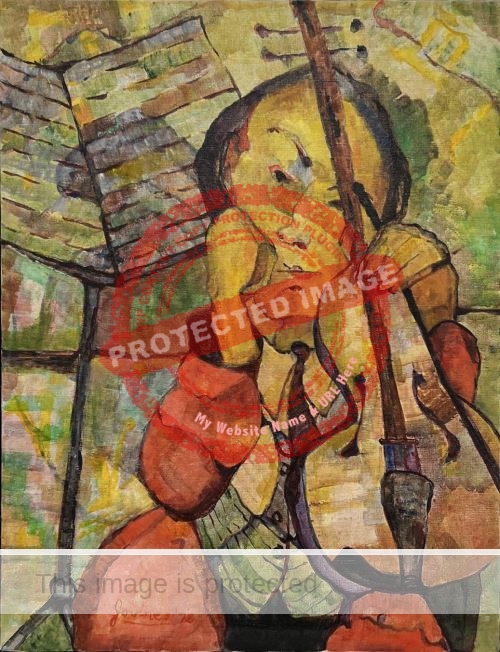

Irma Rene Koen. c 1945. “Street in Ajijic.”

Koen sold almost all her paintings to collectors. The only image I have ever seen of any of her Lake Chapala paintings is of one entitled “Street in Ajijic,” which she presented to the Rock Island YMCA in 1948. (left) If you own, or have access to, any of her other Lake Chapala paintings, please get in touch!

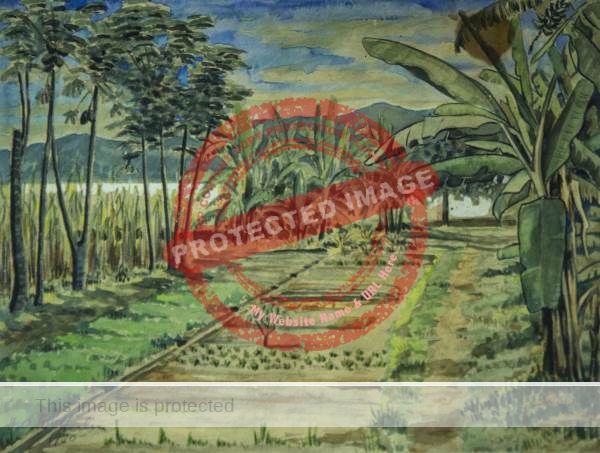

During her thirty years in Mexico, Koen traveled and painted throughout the country, with extensive trips also to Central America (Guatemala), Spain, Japan, Hong Kong, Kashmir, Nepal, and Iran.

Her vivid oil paintings, watercolors and plein-air landscape scenes were widely exhibited during her lifetime, at galleries and museums in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., as well as in Paris (1923) and Mexico.

Koen was a prolific exhibitor throughout her life. In addition to dozens of shows in the US, her paintings were displayed in the Galeria de Arte Mexicano (Gallery of Mexican Art) in Mexico City in 1956, and, in 1968, a selection of her Mexican landscapes and markets was hung at the Galeria de Edith Quijano, also in Mexico City. The following year, an exhibit of her oil paintings was held in the Palacio de Cortés, the main museum in her adopted home of Cuernavaca.

Koen died in Cuernavaca in 1975.

A major retrospective of her work, entitled “Irma René Koen: An Artist Rediscovered,” was held in 2017 at the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa.

Note: This is an updated and expanded version of a post originally published on 14 July 2014.

Main sources:

- Website about Irma René Koen written and compiled by art historian and biographer Cynthia Wiedemann Empen.

- Guillermo Rivas. 1948. “Irma René Koen,” Mexican Life, Vol 24 (1948), Feb 1948.

- The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois) 05 Sep 1946, 12.

- The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), 16 Oct 1948, 16.

- The Des Moines Register, Iowa, 13 Feb 1949, 36

Commenting that “very few Americans have ever heard of Lake Chapala”, Carson described how “a number of pretty villas are dotted along the lake’s edge, embowered in bougainvillea and hibiscus, palms and orange trees. ” The popularity of the village had led to some land speculation:

Commenting that “very few Americans have ever heard of Lake Chapala”, Carson described how “a number of pretty villas are dotted along the lake’s edge, embowered in bougainvillea and hibiscus, palms and orange trees. ” The popularity of the village had led to some land speculation:

Joe Vines, sometimes mistakenly spelled as either Jo Vines or Joe Vine in contemporaneous news reports, was a male artist who signed his work “Jovines.” He held a solo show in March 1968 at the “Galería Ajijic Bellas Artes,” administered by Hudson and Mary Rose, that was located at Marcos Castellanos #15 (at the intersection with Constitución) in Ajijic. Reviewing the show, Allyn Hunt described his work as “sparkling, colorful silkscreen prints.”

Joe Vines, sometimes mistakenly spelled as either Jo Vines or Joe Vine in contemporaneous news reports, was a male artist who signed his work “Jovines.” He held a solo show in March 1968 at the “Galería Ajijic Bellas Artes,” administered by Hudson and Mary Rose, that was located at Marcos Castellanos #15 (at the intersection with Constitución) in Ajijic. Reviewing the show, Allyn Hunt described his work as “sparkling, colorful silkscreen prints.”