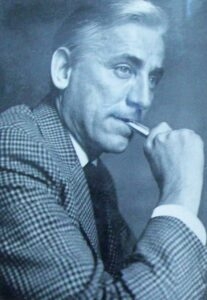

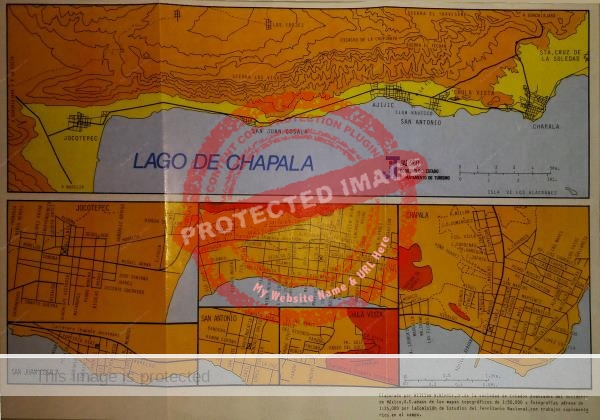

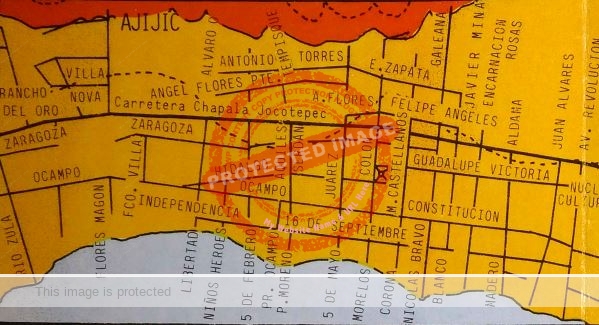

After retiring in the mid-1960s from a career in the U.S. military, Robert (“Bob”) Snodgrass and his wife Mira (sometimes Myra or Maria) lived at Lake Chapala for almost twenty years. They settled in the residential development of Chula Vista, an area that was known at that time as having more than its fair share of musicians and stage performers. Snodgrass proceeded to play an active part in the local theater, music and visual arts communities.

Robert Baird Snodgrass was born in Porterville, California, on 12 September 1912 and died, after a lengthy illness, in Guadalajara on 4 September 1983.

Snodgrass grew up in California and entered the University of California, Berkeley, in the class of ’34. He apparently studied architecture, landscape architecture, art and journalism, before finally graduating with a B.A in Art in 1936. In 1933, as a student, he worked on the Daily Californian, a UC Berkeley publication, and contributed a painting entitled Melting Snow to an exhibition of paintings by students in the classes given by Chiura Obata. In that same year, he also appeared in The Valiant, a play performed by the university’s Armstrong College Thesbians.

In 1935, while still living in Berkeley, he composed and copyrighted (as “Baird Snodgrass”) the music for several songs, including “Dream-in little dreams of you” and “Vanished melody”. The words for both songs were written by Jack Howe.

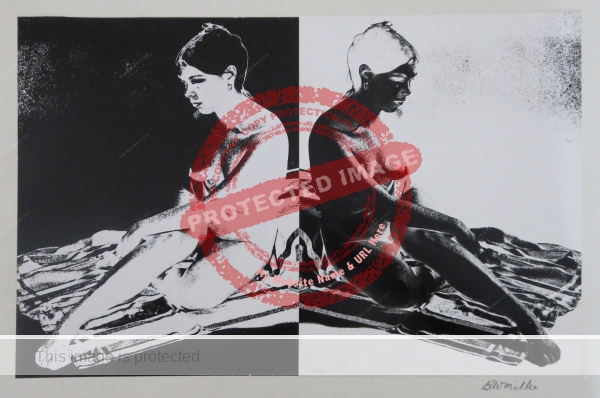

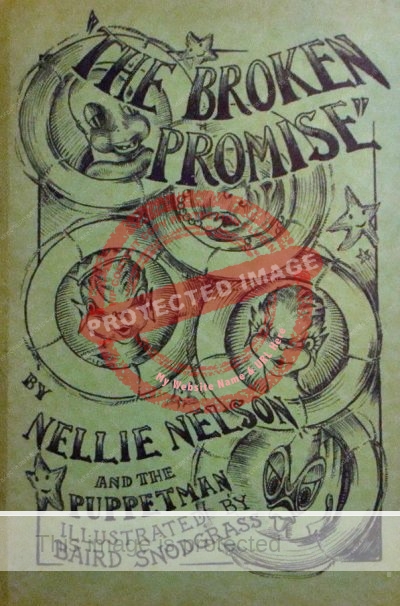

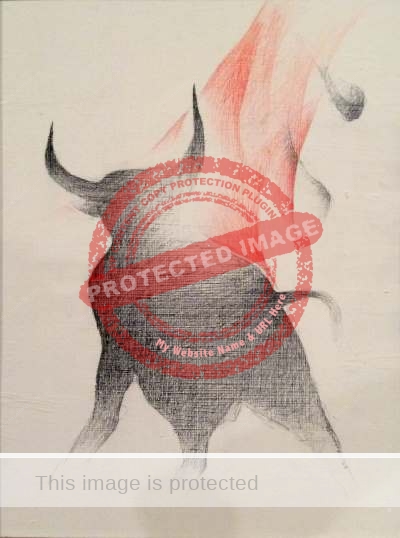

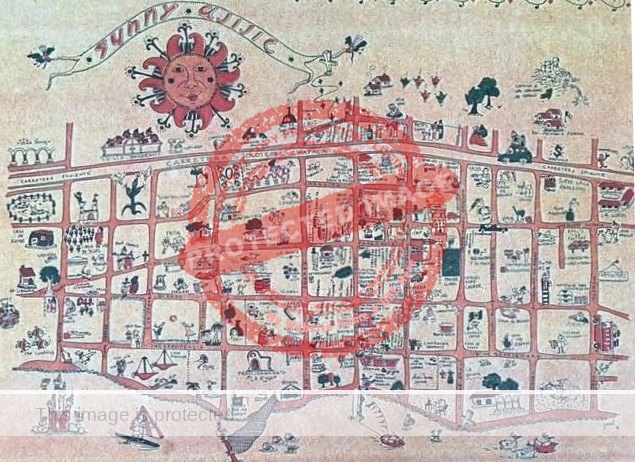

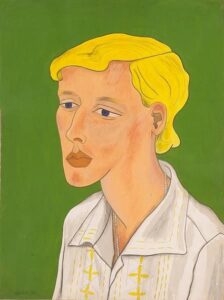

Illustration by Robert Baird Snodgrass for The Broken Promise

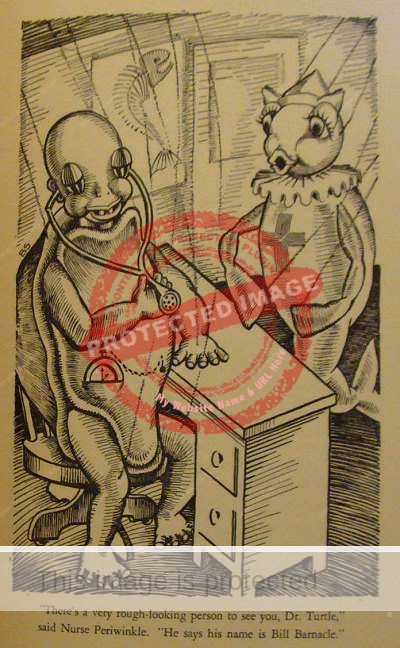

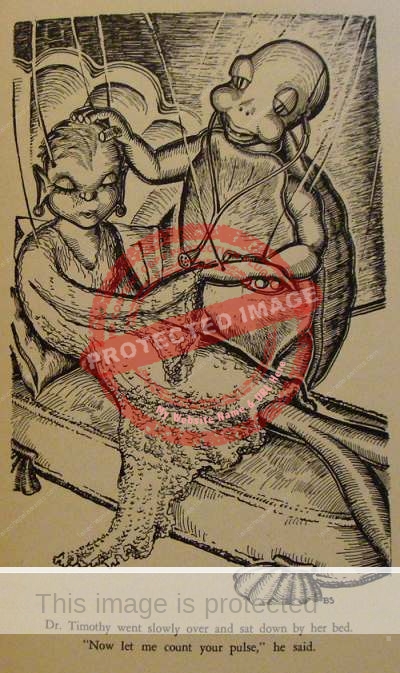

He also drew several delightful illustrations for a puppet play book entitled The Broken Promise, written by “Nellie Nelson and The Puppetman”, published three years later.

Illustration by Robert Baird Snodgrass for The Broken Promise

From Berkeley, Snodgrass moved to Los Angeles where he studied drama and theater arts and had parts on several weekly radio shows.

It is unclear when he married Mira, but the US Census for 1940 has the couple living in Berkeley. Snodgrass’ employment is given as editor of “Rural Magazine”.

In March 1942, only months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Snodgrass enlisted in the U.S. military. After graduating with the twenty-fourth class of engineer officer candidates at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, he received a commission as second lieutenant in the corp of engineers. During his first stint of service he served four years before returning to civilian life in May 1946. He then had two years playing in New York City night clubs, including the 1-2-3 Club on East 54th Street, before re-enlisting with the Army in June 1948. By the time he retired he had risen to the rank of colonel.

Snodgrass “retired” to Lake Chapala in about 1965, two or three years prior to his final, official, release from the military. In retirement, Snodgrass put his earlier education in architecture and landscape planning to good use, designing and building several homes and gardens in the Lake Chapala area.

His earliest recorded contribution to Lakeside theater was painting a nude which hung on the set in June 1965 for The Saddle-Bag Saloon, a musical written and directed by Betty Kuzell. The official history of the Lakeside Little Theater (then known as the Lake Chapala Little Theater) claims this was the group’s first ever show. Snodgrass was also a member of the short-lived Lake Chapala Society of Natural Sciences .

Snodgrass loved to draw and paint and a short article in the Guadalajara Reporter in 1965 stated that he had become interested in archaeology and was “using his talents as an artist to do illustrations of the “finds” of this area for a book to be published and for museum use.” The writer pronounced Snodgrass’ drawings of the artifacts to be “beautifully perfect”. It is unclear which book this article refers to, or if his drawings were ever published.

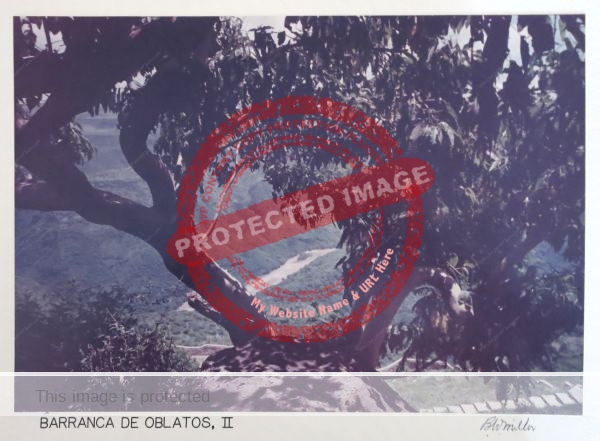

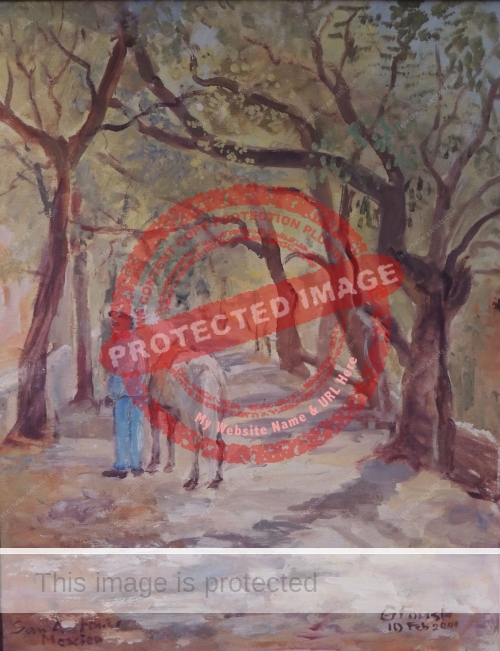

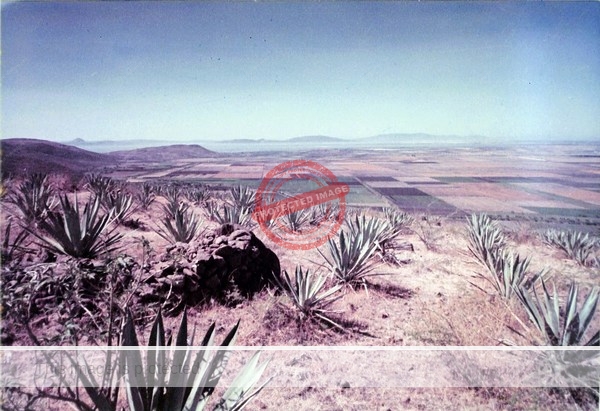

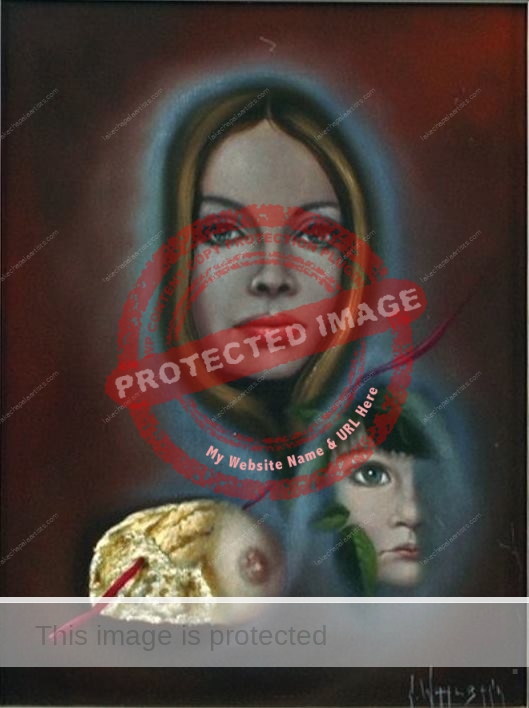

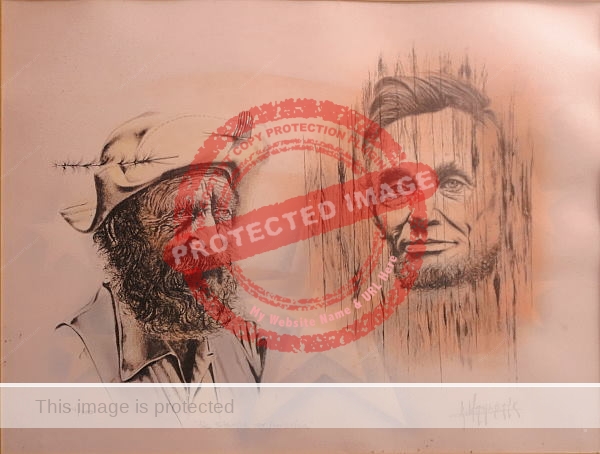

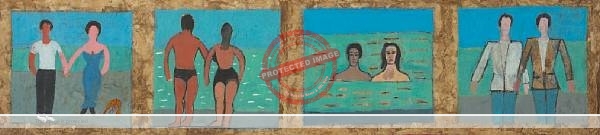

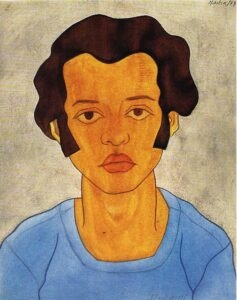

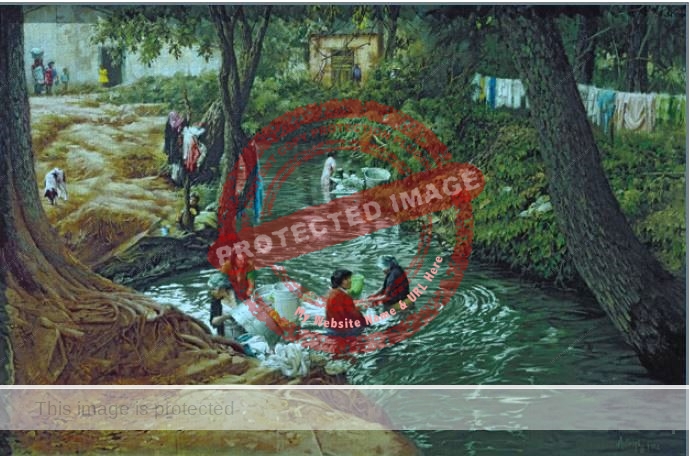

Robert B. Snodgrass. 1968. Untitled. Reproduced by kind permission of Katie Cantu.

As a painter, Snodgrass had a one-person show at La Galería in Ajijic in March 1969 and one or more of his paintings was still on view the following month when the original five members of Grupo 68 (Peter Huf, his wife Eunice (Hunt) Huf, Jack Rutherford, John Kenneth Peterson and Don Shaw) had a collective exhibit at the same gallery.

Snodgrass also exhibited in the large group show, Fiesta de Arte, at the Ajijic home of Mr and Mrs E. D. Windham (Calle 16 de Septiembre #33) in May 1971. Other artists in that exhibition included Daphne Aluta; Mario Aluta; Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; Tom Faloon; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Peter Huf; Eunice (Hunt) Huf; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Gail Michael (Michel); Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; John K. Peterson; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; and Agustín Velarde.

Ever generous, one of Robert Baird Snodgrass’ last artistic actions was to bequeath his easel and paintbrushes to his good friend and fellow artist Georg Rauch.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Katie Goodridge Ingram and Phyllis Rauch for sharing with me their personal memories of Bob Snodgrass and to Katie Cantu for permission to reproduce the image of one of his paintings.

Sources:

- Berkeley Daily Gazette: 19 April 1933.

- Guadalajara Reporter: 10 June 1965; 28 Oct 1965; 5 Mar 1966; 29 Mar 1969; 10 Sep 1983, p 18 (obituary).

- Nellie Nelson and The Puppetman. 1938. The Broken Promise, illustrated by Baird Snodgrass (Los Angeles: Suttonhouse, 1938) 36 pages.

- Reno Gazette: 10 March 1943.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

He is included in this on-going series of profiles because in 1992, he self-published a 48-page booklet entitled Lake Chapala: A literary survey; plus an historical overview with some personal observations and reflections of this lakeside area of Jalisco, Mexico. The book was dedicated to

He is included in this on-going series of profiles because in 1992, he self-published a 48-page booklet entitled Lake Chapala: A literary survey; plus an historical overview with some personal observations and reflections of this lakeside area of Jalisco, Mexico. The book was dedicated to

During one of several visits to Korea during the Korean War, Gammack witnessed the first exchange of sick and wounded prisoners of war. He secured an exclusive radio and TV interview with Iowan Richard Morrison, the first American soldier released.

During one of several visits to Korea during the Korean War, Gammack witnessed the first exchange of sick and wounded prisoners of war. He secured an exclusive radio and TV interview with Iowan Richard Morrison, the first American soldier released.