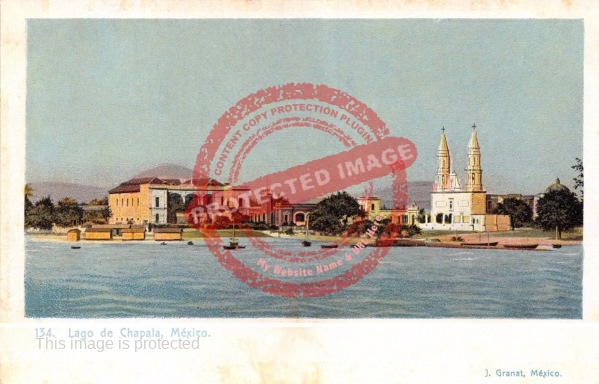

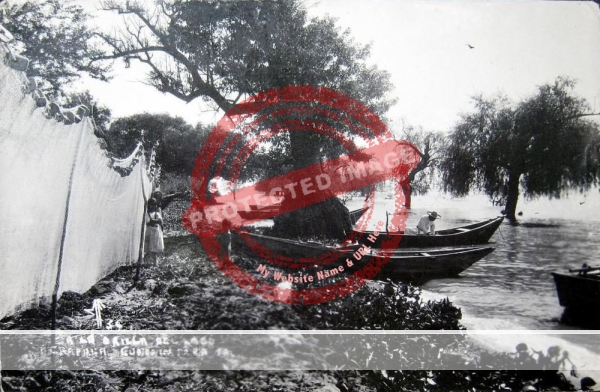

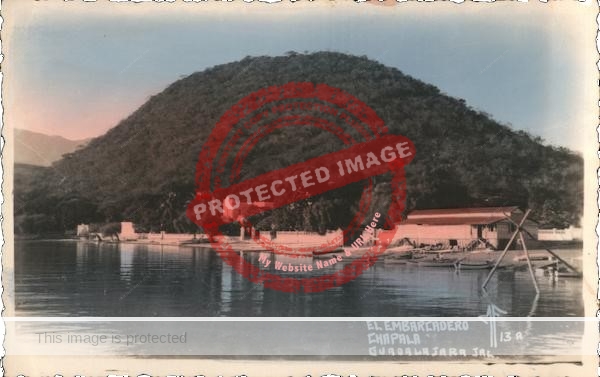

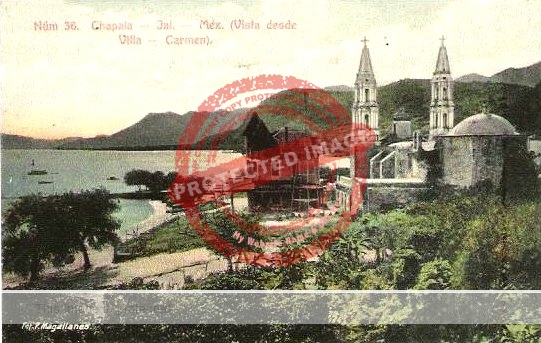

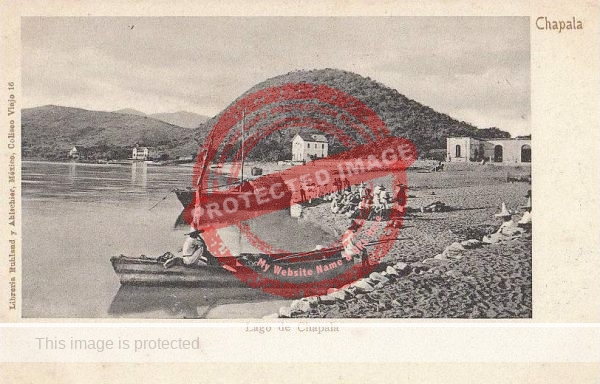

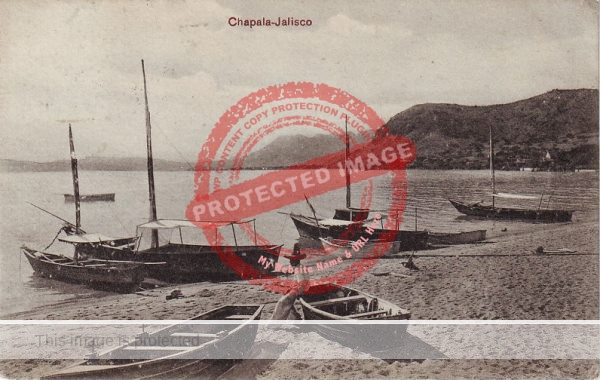

Librería Ruhland & Ahlschier, publisher of the earliest illustrated postcards of Mexico, was a bookstore in Mexico City owned by Emil Ruhland and Max Ahlschier. The store advertised as “Libreria Internacional de Ruhland & Ahlschier” and was located at Coliseo Viejo #16. The company published at least seven different postcards of Lake Chapala, including views of the shoreline, boats, church, plaza (jardín) and a stagecoach. Two of the photographs were also published, at about the same time, by Juan Kaiser in Guadalajara. Kaiser and Ruhland were apparently close friends.

Ruhland & Ahlschier were commissioned to provide the first ever series of illustrated postcards for the Mexican Post Office in 1897. All previous postcards (which at that time were postage paid and purchased in a post office) had one side for correspondence and the other side pre-stamped and reserved for the address. As illustrated cards became popular in Europe and then in the U.S., the Mexican government saw the advantages of issuing its own illustrated cards, which required the purchaser to purchase postage stamps separately and affix them to the card prior to mailing.

These beautifully-produced and inexpensive souvenir postcards soon spurred a new market for collectors; many of the art cards, especially, were far too pretty to entrust to the vagaries of being sent through the mail without an envelope to protect them. In consequence, relatively few postally-used examples exist of many of the more attractive cards.

Demand for illustrated postcards grew rapidly. When the postal service relaxed its regulations, several private firms entered the market, each producing their own illustrated cards and selling them through hotels and a wide variety of stores and other outlets.

Illustrated cards still reserved, prior to 1906, one entire side for the address and stamp, meaning that any message or correspondence had to be written on the same side as the image. The first postcards to have divided backs, allowing for both correspondence and address on the reverse, thereby leaving the entire front side of the card for the image, were released in the UK (1902), then mainland Europe and Mexico (1905), and the U.S. (1907); they were legal to mail in the U.S. from 1 March 1907.

The two men who owned Ruhland & Ahlschier are something of an enigma. Emil Ruhland and Max Ahlschier were both born in Germany. Ruhland, born in about 1847, left Germany in about 1869 and was certainly established in Mexico City by 1883 when he is named as the editor of Deutsche Zeitung von Mexiko, a newspaper for the German-speaking community in the city. In 1888 he partnered with Isidoro Epstein to found (and co-edit) another German newspaper, Germania. Ruhland’s name continued to be associated with Deutsche Zeitung von Mexiko until at least 1897, by which time Max Ahlschier was his co-editor.

In 1888, Ruhland edited and published the Directorio General de la Ciudad de México, a forerunner of the telephone directory and later commonly referred to simply as Directorio Ruhland. City directories were especially important following the introduction of the telephone to Mexico in the 1880s. By 1893 telephone services existed in 14 cities even though intercity lines would not become available until much later.

The first edition of Directorio General de la Ciudad de México in 1888 cost $1.60 (paper cover) or $2.00 (cloth cover). New editions of the directory appeared more or less annually thereafter for more than twenty years. The 500-page 1892 version, “more complete than ever,” cost $3.00 and had four parts: the names of residents and industries and their place of residence; a listing of professional men, merchants and manufacturers; contact details for all government offices and heads of departments; and listings for railroads, the press, societies and ecclesiastical figures. Ruhland published a similar volume for Guadalajara in 1894.

Ruhland’s directories proved to be extremely popular and a commercial success. At the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, Ruhland won an award for his guides to the Mexican republic. The following year, the 1896-1897 edition of his directories went on sale in Mexico City at his own store (Avenida Cinco de Mayo #4) and at the bookstore of F. P. Hoeck (San Francisco #12) as well as in New York (E. Steiger & Co., 25, Park Place) and London (Dulan & Co, 37, Soho Square).

Emil Ruhland’s association with Max Ahlschier seems to have begun in 1897. We know little about Ahlschier beyond the fact that he was born in Germany in 1867 and married Anna Vogt, also from Germany, in Mexico City on 4 June 1903. The Lutheran service was held at the Casino Alemán.

The two men opened their joint bookstore, Librería Ruhland & Ahlschier, and also began to publish pictorial postcards. Publicity for their store in 1897 shows that it sold, among other items, American books, literature, American and German paper, pencils, pens, inks, maps of Mexico and illustrated postal cards with views of Mexico.

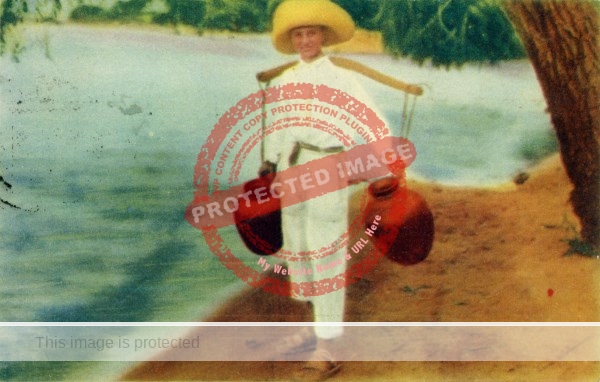

The earliest Ruhland & Ahlschier cards were black and white or sepia collotypes; later cards were produced by chromolithography. Though their postcards do not identify the photographer, their stable of photographers included some important names in Mexican photography, including German-born Guillermo Kahlo (the father of Frida Kahlo), Guadalajara-native José María Lupercio, and American photographers Winfield Scott and Charles B. Waite.

Guillermo Kahlo (born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo) (1872-1941), who first arrived in Mexico City in 1891, at the age of 19, learned his craft in Mexico and was mainly known as a commercial photographer; his photos were first turned into postcards by “Ruhland & Ahlschier” in about 1903.

Charles Betts Waite (1861-1927) set up shop as a photographer in Mexico City in 1896 and amassed a vast collection of thousands of images taken all over Mexico. In 1908 he bought all the “photographic view negatives” of Winfield Scott, and advertised that he now had “the largest assortment of views of any one country in the world.”

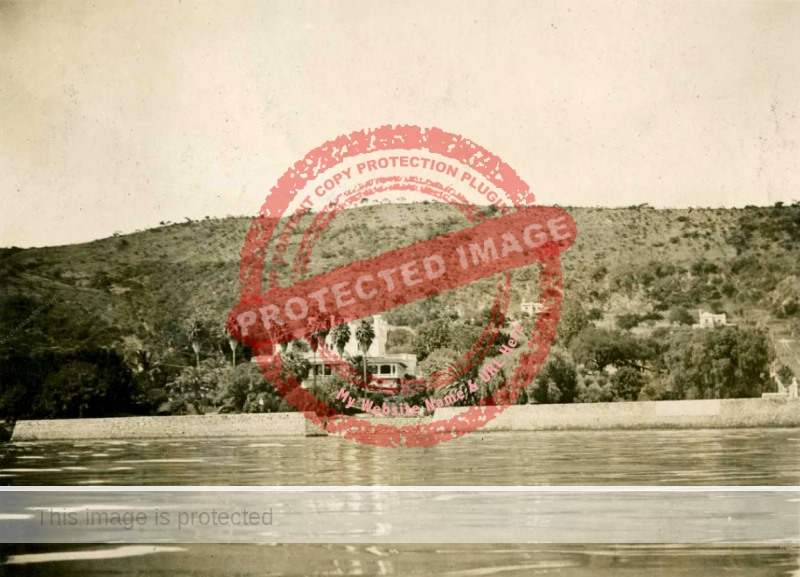

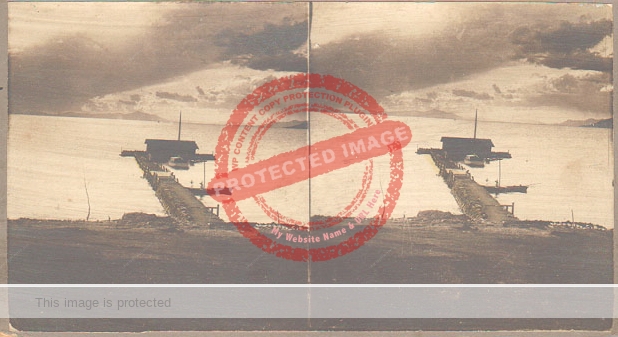

Winfield Scott. c 1897 (published c 1902). Beach, Chapala.

Winfield Scott was responsible for the photograph on this Ruhland & Ahlschier postcard (above), a photograph now in the collection of Mexico’s National Photo Archive. The photo shows fishermen sitting on a boat in front of the beach, with the Casa Capetillo in the middle background. To the right, only the first story of the Hotel Arzapalo has been built, dating this particular image (though not the card) to 1896-1897. The two-story hotel opened in 1898, and Winfield Scott was its manager when D. H Lawrence visited Chapala in 1923.

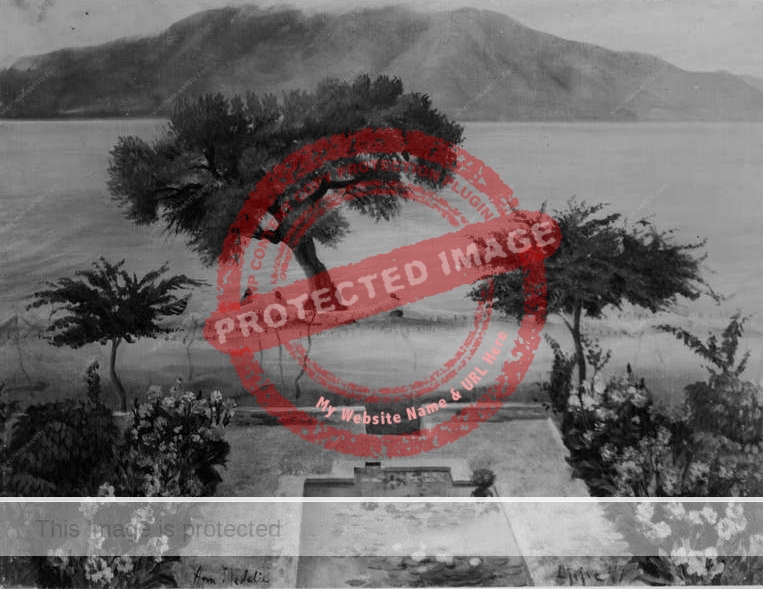

José María Lupercio. c. 1900 (published c 1904). Carden’s garden, Chapala.

The National Photo Archive also has this Lupercio photo of the garden of Villa Tlalocan, the vacation home in Chapala of British consul Lionel Carden and his wife. The home was completed in 1896 and this postcard shows ornamental flower vases in the front garden, with the lake behind and Chapala’s San Francisco church in the distance.

Early cards published by Ruhland & Ahlschier have the imprint “Librería Ruhland y Ahlschier, México, Coliseo Viejo 16.” In about 1903, the two men sold their business, and later postcards (published from 1904 on) have a different imprint: “Ruhland & Ahlschier Sucr. Calle Espiritu Santo 1½, México.” This was the address of La Sociedad Müller y Cia, owners of a competing bookstore, Librería Internacional.

By 1909, Müller and Company had also acquired ownership of, and the rights to publish, Ruhland’s Directorio general de la ciudad de México. The 1909-1910 edition was published in two volumes, one for Mexico City and one for the rest of the country. Müller and Company continued to publish the directory until at least 1913.

What became of Emil Ruhland and Max Ahlschier, pioneers of the Mexican illustrated postcard?

Ruhland revisited Germany in 1899 after an absence of 30 years, before returning to Mexico. Four years later (1903) he appears to have moved to the U.S., at about the time the postcard publishing company was sold. He was a good friend of Juan Kaiser, and Kaiser’s wife, Bertha, records the two men meeting for the first time in twelve years in Los Angeles in 1915.

Ahlschier and his wife visited Europe in 1906. Two years later, he was elected secretary of the Sociedad Alemana de Beneficencia (German Benevolent Society) in Mexico City. In 1912 he lost a civil action brought by a Martin G Ribon and was ordered to pay $3371.08 plus costs.

It seems likely that he and his wife subsequently returned to live in Germany, given that a Max Ahlschier is listed in trade directories there as a publisher between 1928 and 1933. Support for the idea that he returned to Germany also comes from an unusual source. In the Library of Congress’s vast collection of German documents, captured by American military forces after World War II, is a record of one by Max Ahlschier entitled “German colonies in Mexico, 1890-1910.”

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Note: This post was first published 9 August 2019.

Sources

- Atlanta Constitution, 22 Nov 1895, 1.

- El Continental, 13 May 1894, 3.

- El Diario del Hogar, 3 Feb 1912, 3.

- Diario Oficial Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 19 Jan 1905; 13 June 1908; 16 July 1909; 17 Oct 1912.

- El Imparcial, 7 June 1903, 2.

- Jalisco Times, 10 Apr 1908.

- Verena Kaiser-Ernst. 2012. Tagebuch Von Bertha Kaiser-Peter Fur Ihren sohn Hans Paul Kaiser. Stuttgart: T H Schetter, 45.

- The Mexican Herald: 6 Sep 1896, 9; 6 July 1897, 8; 3 May 1899, 8.

- El Mundo, 1 April 1897.

- La Patria, 28 Aug 1883, 8.

- El Partido Liberal, 7 June 1888, 2.

- The Two Republics, 31 Oct 1888, 2; 20 Feb 1892, 1.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

I was barely able to contain my excitement. The Johnsons were an

I was barely able to contain my excitement. The Johnsons were an

![Louis Stettner. Lake Chapala (1956). [postcard image on Delcampe website]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/stettner-louis-1956-chapala-s.jpg)