John Kenneth Peterson, known in his family as “Kenny”, was born in San Pedro, Los Angeles, on 24 September 1922, to Andrew Gustof Peterson (1886-1957) and Edith Anna Danielson (1892-1973). He passed away in Ajijic, Mexico, in 1984, at the age of 61, and is buried in San Diego.

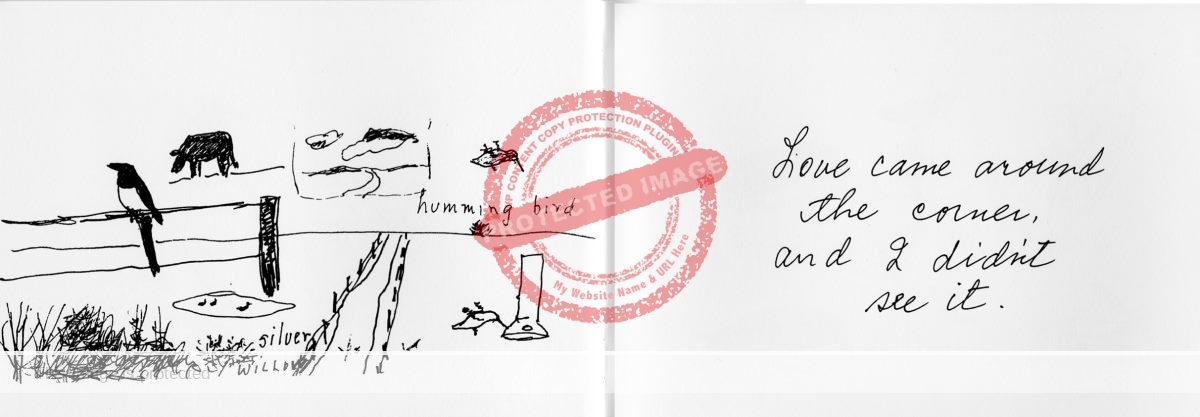

Peterson was active in the Ajijic art community, for some twenty years, living from sales of his art and teaching from when he first arrived in the village in the mid-1960s.

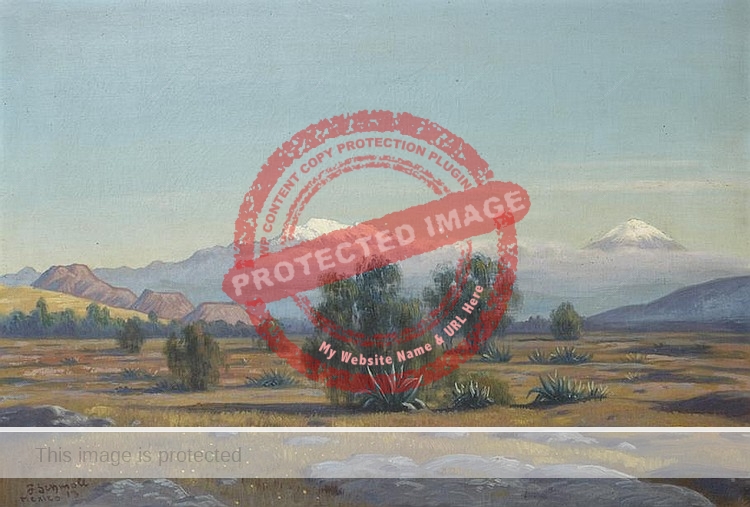

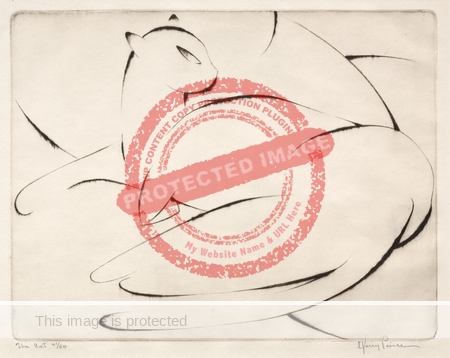

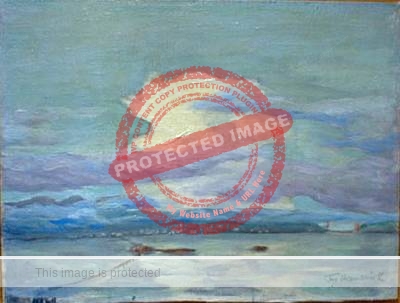

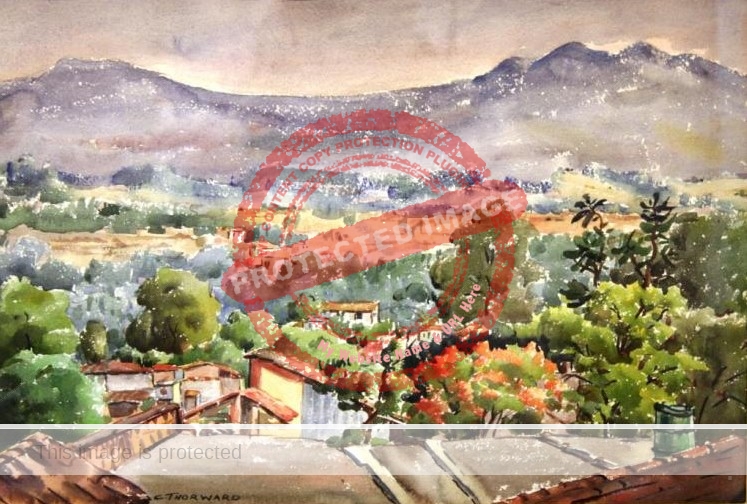

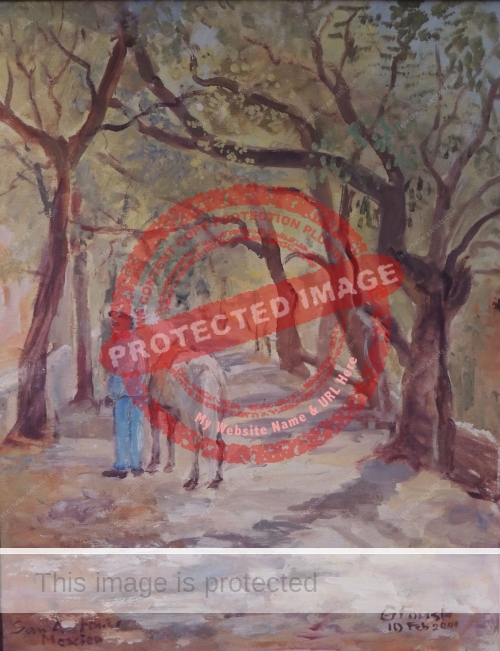

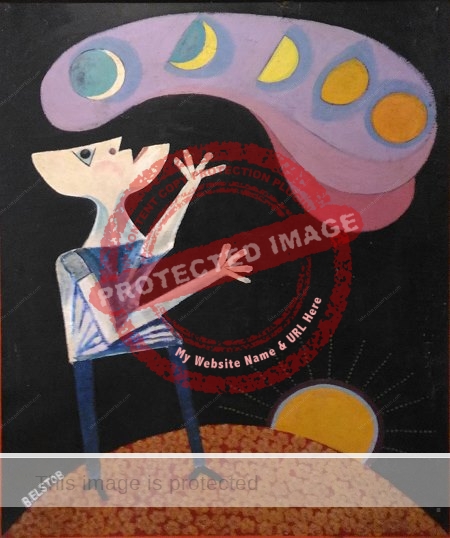

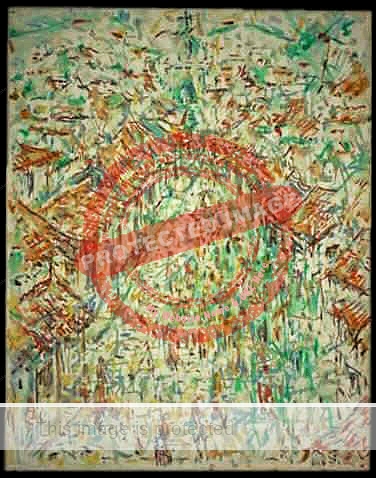

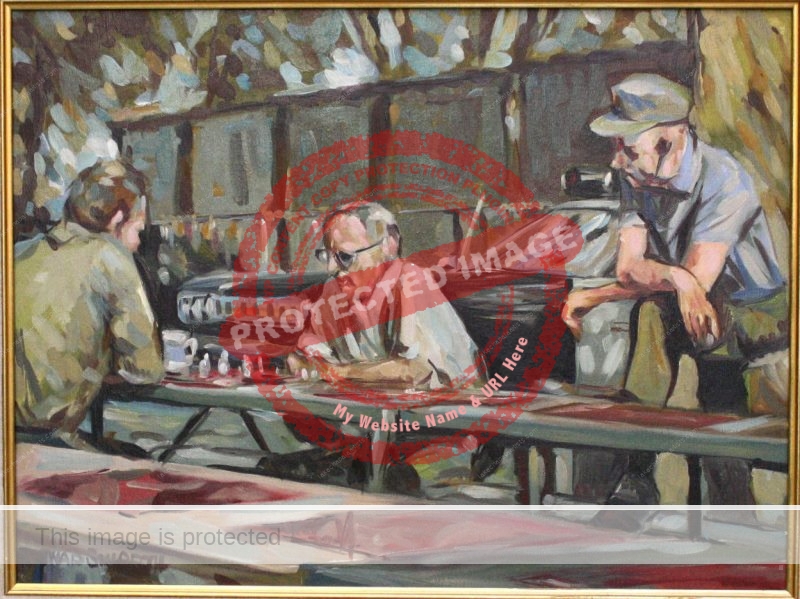

John K. Peterson. “Lago Chapala” (1973)

As a child, Peterson began painting at the age of five, while recuperating from a serious illness. He graduated from Point Loma High School in San Diego in 1941. Two years later, he began a three-year stint in the U.S. Navy. On 24 June 1944, a year after entering the Navy, Peterson, 5′ 11″ tall with blond hair and blue eyes, married Josephine Ornelas. They had met in Bangor, Maine, and married in Orlando, Orange County, Florida. Ornelas was born in 1926 in El Paso, Texas, into a family originally from Chihuahua, Mexico. After an early career in modeling, she became one of the first female police officers in Richmond. The couple had three children: two girls and a boy, but separated and divorced in the mid-1960s.

After the war, Peterson, who had completed a few murals and portraits on his own time during his stint in the Navy, tried a succession of jobs, before opting to use his G.I. Bill entitlement to study at the Coronado School of Fine Arts in Coronado (near San Diego), California. He studied there four years (1948-1952), spending several summers (1949, 1950 and 1952) in Guadalajara. His tuition was covered by G.I. funds and scholarships.

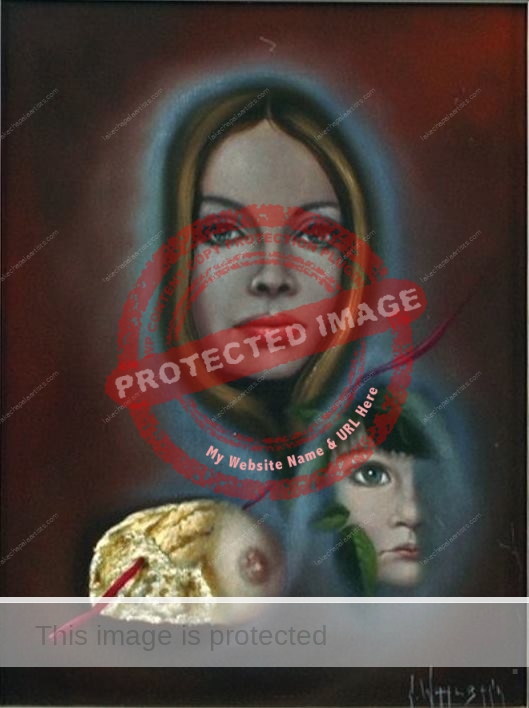

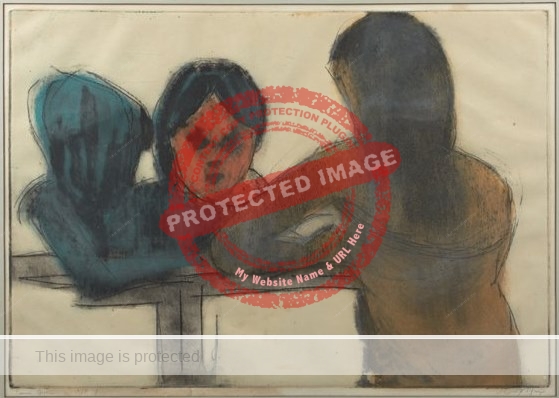

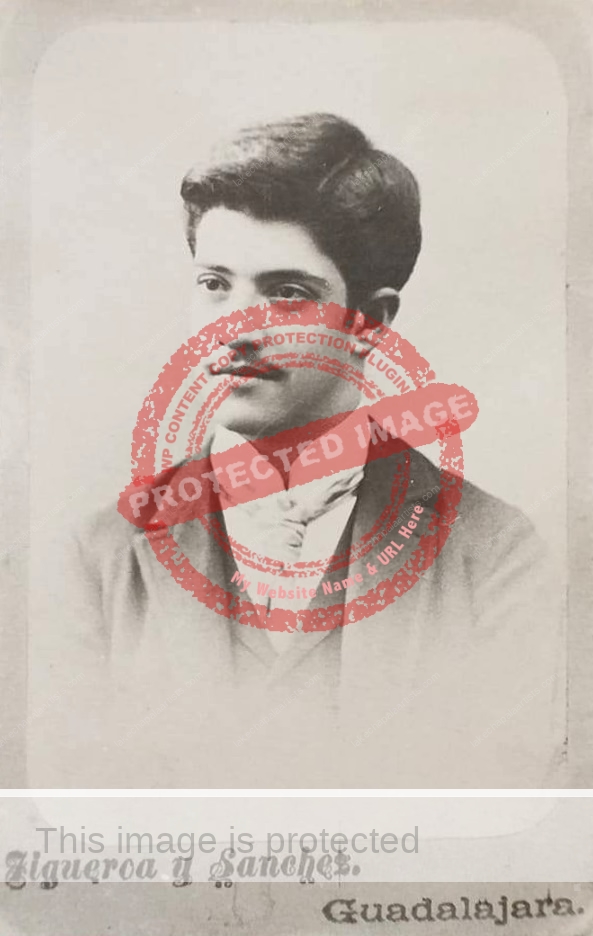

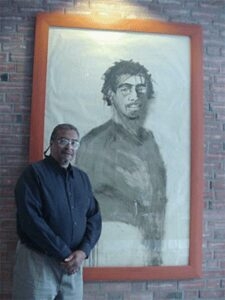

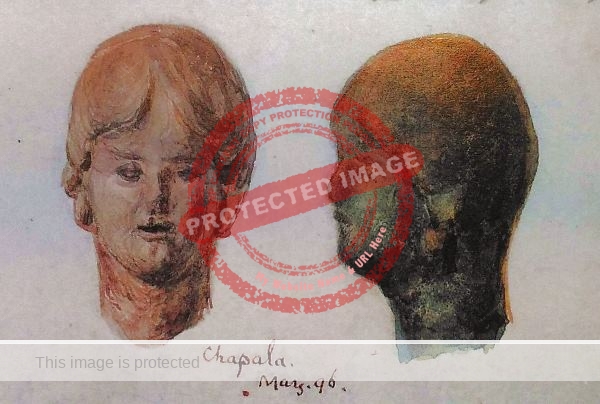

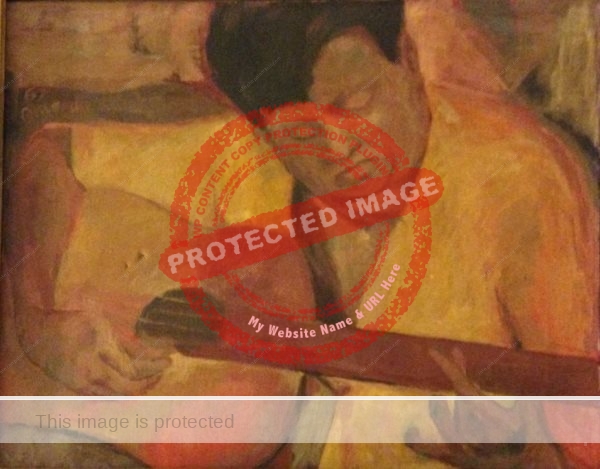

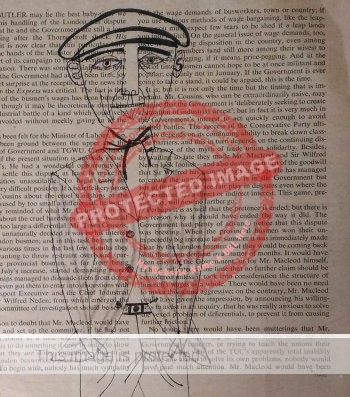

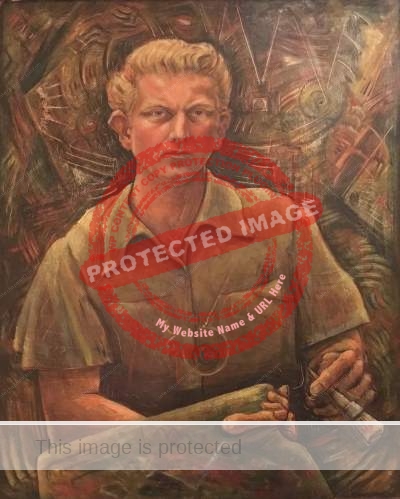

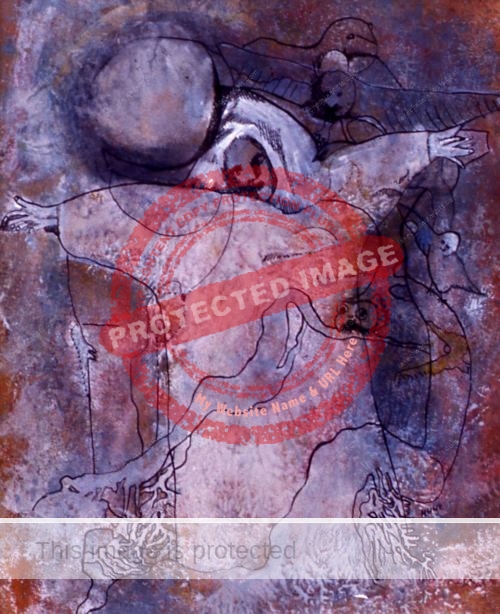

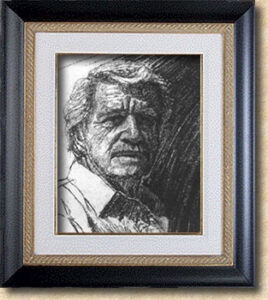

John K Peterson. Mirror image self-portrait. ca 1952. Reproduced by kind permission of Monica Porter.

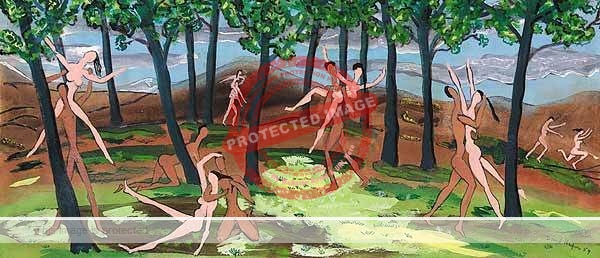

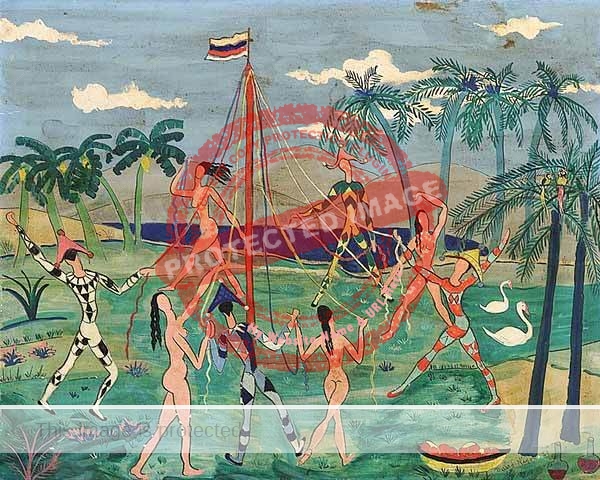

He stayed on at the Coronado School of Fine Arts to teach watercolor techniques and engraving until 1954. During his time in the San Diego area, he completed seven murals in Coronado, and one – “Tahitian Dancers” – in 1952 at the Navy Fleet Sonar School. Peterson’s self-portrait from this time remains a prized family possession.

His art teachers included Monty Lewis, José Martinez [Guadalajara] and Dan Dickey (oils and frescoes), Donal Hord (sculpture), F. Robert White (drawing and etching), Eloise Bownan (portraiture), Frederick O’Hara (wood block cutting) and Rex Brandt, James Cooper White, Dong Kingman and Noel Quinn (watercolors). By coincidence, Kingman had also taught another long-time Lakeside artist, Eleanor Smart.

Throughout his life, Peterson was always ready to play a part and a San Diego newspaper from 1952 has a photograph of him lounging in fancy dress at the “Third Annual Costume Arts Ball”, held in Hotel del Coronado. More than twenty years later, he won first prize at the 1973 Halloween Costume Dinner Dance organized by the Tejabán restaurant in Ajijic. In the mid-1970s, Peterson was persuaded by hotelier Morley Eager, the newly-arrived proprietor of the Posada Ajijic, to dress up as Santa Claus to distribute presents bought by the Eagers for the village children. He may have been the first Santa the village kids had seen. According to Terry Vidal, who reviewed hundreds of paintings done over the years by young artists in the Lake Chapala Society’s Children’s Art Program, the earliest children’s art to feature Santa Claus dates back to about the same time.

Peterson’s two most noteworthy artistic achievements during his few years in Coronado were opening his own gallery, The Sidewalk Studio (131, Orange Ave.) in 1953, and winning the “People’s Choice” award at the 2nd annual exhibition of San Diego county artists in that same year, for a watercolor entitled “Red Can”.

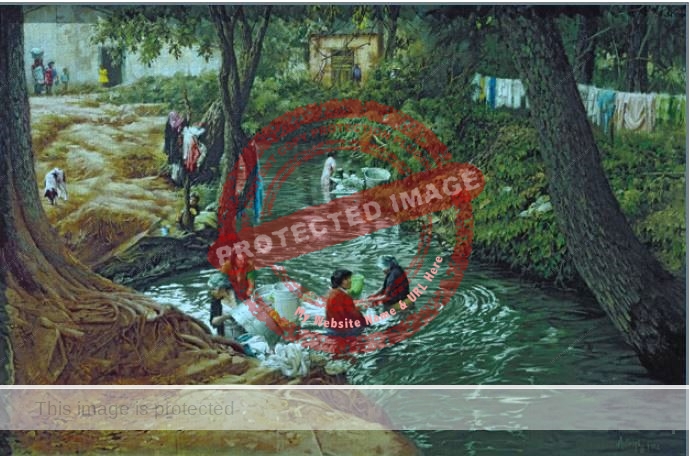

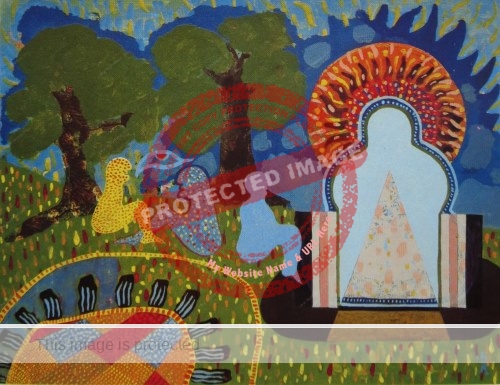

John K Peterson. Laundry day, Ajijic. 1965.

In December 1954, Peterson moved to the San Francisco Bay area and entered the commercial art world, establishing the family home five years later in Point Richmond. He worked as an illustrator-engraver at Fiberboard & Co. in San Francisco, and also opened a gallery, the Triangle Art Gallery (TAG), in partnership with fellow artists Herbert Wasserman and Richard Godfrey. TAG (at (267 Columbus Ave.) opened in June 1956 with a showing of works by the three partners. Two months later, a show of drawings, lithographs and etchings by Richard Diebenkorn, James Budd Dixon, Walter Kuhlman, Edwin Durham and Frank Lobdell, together with sculpture by Sargent Johnson opened at TAG.

TAG hosted a North Beach Artists Group Show in December 1956, followed by an exhibit of paintings by Toshi Sakiyama in February 1957. A month later, a one person show of works by Peterson opened at TAG. The original TAG (another gallery of this name operated in San Francisco from 1961 to 2011) held its 1st Annual Exhibition from 16 June to 13 July 1957.

Peterson was accepted into the San Francisco Art Association (one of oldest in the U.S., and the oldest in California) in 1958, his work having been “previously exhibited in several of the SFAA annual shows”.

After about a decade in San Francisco, Peterson moved to Los Angeles in about 1962 and took a position as art director and illustrator at the Sterling Die Co. After two years in this position, Peterson, now separated from Josephine Ornelas, moved to Guadalajara. He lived and painted in the city during 1964 and 1965 before deciding to improve his prospects by moving to the village of Ajijic on Lake Chapala. Within months, he had opened a studio-gallery and was giving private art classes to help make ends meet. Apart from vacation trips and a spell in San Diego Veterans Affairs hospital, he lived in Ajijic for the remainder of his life.

Living in Ajijic proved to be a wise decision. Peterson found time to focus on his art and participated in an extraordinary number of exhibits during his time in the village.

He was a founding member of both Grupo 68, an Ajijic art co-operative that was active from 1967 to 1971, and Clique Ajijic, the loose collective that succeeded it in the mid-1970s.

Other members of Grupo 68 included Peter Huf, his wife Eunice (Hunt) Huf, Jack Rutherford and Don Shaw. The members of Clique Ajijic included Sidney Schwartzman, Adolfo Riestra, Gail Michaels, Hubert Harmon, Synnove (Shaffer) Pettersen, Tom Faloon and Todd (“Rocky”) Karns.

The earliest show I’ve found recorded for Peterson in Mexico was in a group show by the four main members of Grupo 68 and friends at El Palomar in Tlaquepaque which opened on 20 January 1968. (Other artists on that occasion included Gustavo Aranguren, Peter Huf, Eunice Hunt, Rodolfo Lozano, Gail Michael, Hector Navarro, Don Shaw and Thomas Coffeen Suhl.) This was the start of regular Friday exhibits at the store.

From early in 1968, Peterson exhibited regularly (most Sunday afternoons) in Grupo 68 shows at the Hotel Camino Real in Guadalajara, and in many group shows in Ajijic, some at Laura Bateman’s Rincón del Arte gallery, and (later) in “La Galería”, the collective gallery the artists co-founded at Zaragoza #1, Ajijic.

Confusingly, “La Galería” was also the name of an existing gallery in Guadalajara (at Ocho de Julio #878) where the Grupo 68 artists and others (including Tom Brudenell, John Frost, Paul Hachten, Allyn Hunt, Tully Judson Petty and Gene Quesada) participated in the First Annual Graphic Arts Show of prints, drawings, wood cuts in June 1968.

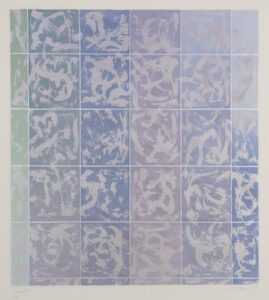

The following month, Grupo 68 was exhibiting in the Tekare penthouse in Guadalajara (16 de Septiembre #157, 10th floor). That show was very favorably reviewed by Allyn Hunt in his “Art Probe” column in the Guadalajara Reporter, 27 July 1968). Concerning Peterson’s work, Hunt wrote that, “John Peterson displays several mosaic-like watercolors, the best of which are his ferris wheel pictures and “Butterfly”.”

Laura Bateman’s gallery in Ajijic, Rincón del Arte, “re-opened” in September 1968 as an artists’ co-operative, nominally headed by Grupo 68 artists, with a group show featuring works by Tom Brudenell, Thomas Coffeen Suhl, Alejandro Colunga, Eunice Hunt, Peter Paul Huf, John K Peterson, Don Shaw, Jack Rutherford and Joe Wedgwood. Grupo 68 joined with Guadalajara artist José María Servín the following month for a show at Galería del Bosque, Guadalajara, sponsored by the Organizing Committee of the Cultural Program for the XIX Olympics, being held in Mexico City.

Peterson held a solo show at Rincón del Arte, Ajijic, in November 1968, mainly comprised of pastels and watercolors, with Allyn Hunt, in his review, describing Peterson as “probably the area’s most provocative artist when dealing with conventional nudes.”

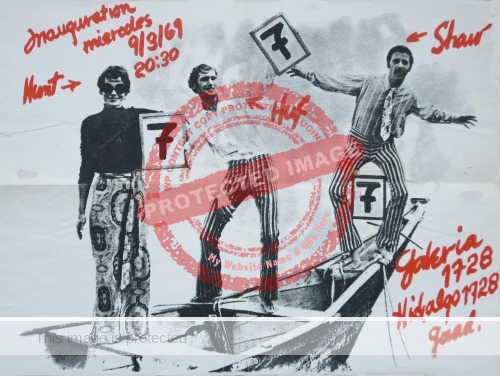

Naturally, Peterson was also involved in the month-long group show entitled “Art is Life; Life is Art” that marked the re-opening of La Galería in Ajijic (at Zaragoza #1) in December 1968. The artists on that occasion were Tom Brudenell, Alejandro Colunga, John Frost, Paul Hachten, Peter Huf, Eunice Hunt, John Kenneth Peterson, Jack Rutherford, José María de Servín, Shaw, Cynthia Siddons, and Joe Wedgwood. Only a few days after that show opened, Peterson was in Guadalajara for the opening of a Collective Christmas Exhibition at Galeria 1728 (Hidalgo #1728) which also featured works by Thomas Coffeen, Gustel Foust, Peter Huf, Eunice (Hunt) Huf and several famous Mexican artists: David Alfaro Siqueiros; Alejandro Camarena; José María Servín and Guillermo Chávez Vega.

Peterson’s pastels and paintings in a group show at La Galería, Ajijic, in April 1969 hung alongside works by Charles Henry Blodgett, John Brandi, Tom Brudenell, Eunice Hunt, Peter Paul Huf, Jack Rutherford, Don Shaw, Cynthia Siddons and Robert Snodgrass.

All four Grupo 68 regulars – Peter Paul Huf, Eunice Hunt, John Kenneth Peterson and Don Shaw – held a show at the Instituto Aragón (Hidalgo #1302, Guadalajara) in June. At the end of that same month, Peterson won 3rd prize in the abstract painting category in the juried show, “Semana Cultural Americana – American Artists’ Exhibit”, marking “American Cultural Week” in Guadalajara. The show featured 94 works by 42 U.S. artists from Guadalajara, the Lake area and San Miguel de Allende.

This was about the time when pulp fiction writer Jerry Murray first arrived in Ajijic and he later recalled how Peterson, “a jovial bearded guy” and “local resident artist” had helped him find a place to rent. Peterson’s studio, says Murray, was “cluttered with half a dozen easels with paintings on them and uncounted half-filled rum, brandy, and soft drink bottles.” Peterson and some of his exploits are also described in Henry F. Edwards’s The Sweet Bird of Youth (2008). In this thinly described, fictionalized autobiography about life in Ajijic in the 1970s, Edwards devotes an entire chapter to “George Johannsen”, a “General Custer lookalike”.

An Easter Art Show at Posada Ajijic in March 1970 saw Peterson exhibiting alongside Peter Huf, Eunice Hunt, John Peterson, John Frost, Don Shaw, Bruce Sherratt and Lesley Jervis Maddock (aka Lesley Sherratt).

In the summer of the following year, Peterson was one of the many artists with works in the Fiesta de Arte held on 15 May in a private home in Ajijic. (Among the artists involved in this show were Daphne Aluta; Mario Aluta; Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; Tom Faloon; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Peter Huf; Eunice (Hunt) Huf; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Gail Michael (Michel); Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; Robert Snodgrass; and Agustín Velarde.

An advert for Peterson’s exhibit in June 1972 at El Tejabán restaurant-gallery says that after the show ends, Peterson is headed to New York for a one-man show. The details of this show remain unclear. It is also referred to in a Guadalajara Reporter profile of Peterson written by Joe Weston in July 1972. Weston describes Peterson as “a blonde, red-bearded Viking giant”, and quotes him as saying that, “I’m not owned by people or money or time… I dance and I drink and I like women and I talk loud and I shout with enthusiasm….” Asked why he likes Ajijic, Peterson responds that, “I like it here, the people, the colors, the general ambience, the way of life, the economics. That’s why I stay. But I’m not tied here. There are probably other places in the world as good or better. When I want to find them, adios!”

Local art critics were invariably impressed by the high quality of Peterson’s work. For example, Allyn Hunt, reviewing Peterson’s solo show at the Camino Real Hotel in Ajijic in September 1972, praised this “dexterous draftsman”, his “excellently-rendered pastels” and his “nimbly-produced sketches”. A year later, Hunt described Peterson’s exhibit at the Tejabán restaurant-gallery: water colors of Mexican street scenes created by slashing pointillist patchwork of pastel color, as well as carnival merry-go-rounds and “a deftly executed series of glowing nudes done in chalk”. Hunt found that the street-scapes were “at once delicate in their filigree form and vigorously bold in their deep overlaying hues”. Novelist and Hollywood screenplay writer Ray Rigby wrote that “John Peterson combines strength and violence with a forgiving hand. His flair for fantasy intermingles with reality… John Peterson’s work is fun.”

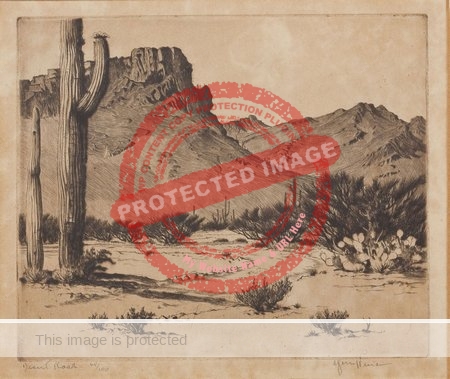

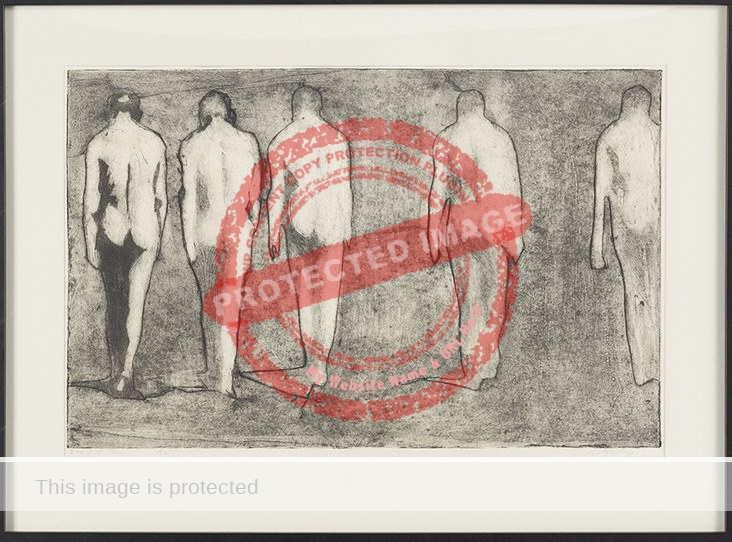

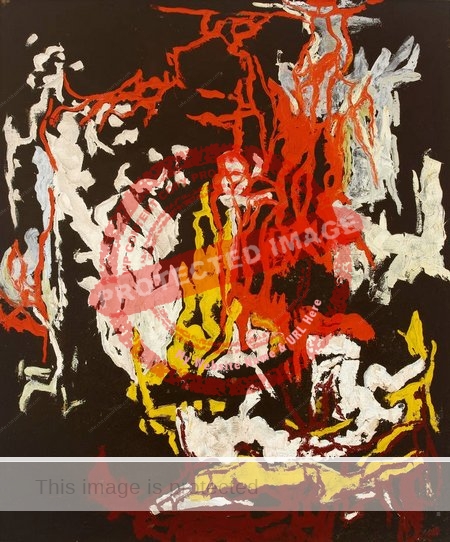

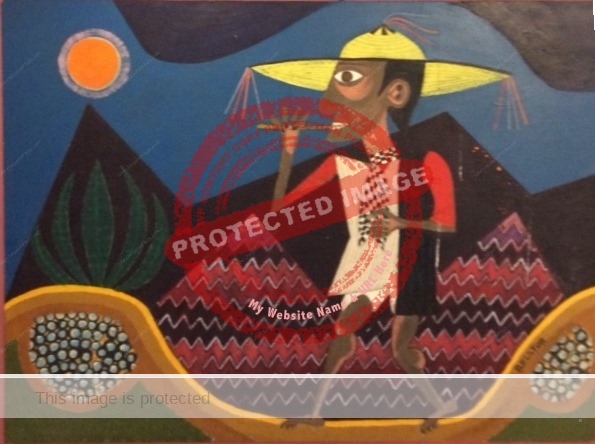

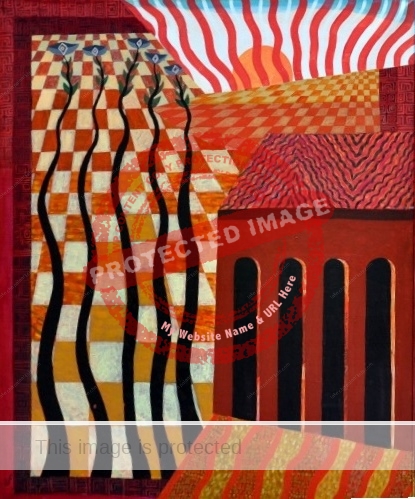

John K Peterson. Funeral Procession. ca 1975

In December 1976, Peterson had work in a group show organized by Katie Goodridge Ingram for the Jalisco Department of Bellas Artes and Tourism, held at Plaza de la Hermandad (IMPI building) in Puerto Vallarta. The show ran from 4-21 December and also included works by Jean Caragonne; Conrado Contreras; Daniel de Simone; Gustel Foust; John Frost; Richard Frush; Hubert Harmon; Rocky Karns; Jim Marthai; Gail Michel; Bob Neathery; David Olaf; Georg Rauch; and Sylvia Salmi.

Peterson’s ability to capture a scene with rapid brush strokes was remarkable. Earl Kemp’s Efanzine of July 2002 (Vol. 1 No. 3) includes the following description of Peterson’s painting of a funeral held in Ajijic: “It [the funeral] was so big, in fact, it inspired local Impressionist painter John K. Peterson to immortalize the event on canvas. His picture shows a street scene looking right down the middle of the street to where, three blocks away, the Cathedral stands. From every doorway the townspeople are pouring, as if on cue, and forming a funeral procession down the center of the street to the church where the ceremony in honor of the passing of Pepe’s father would take place.”

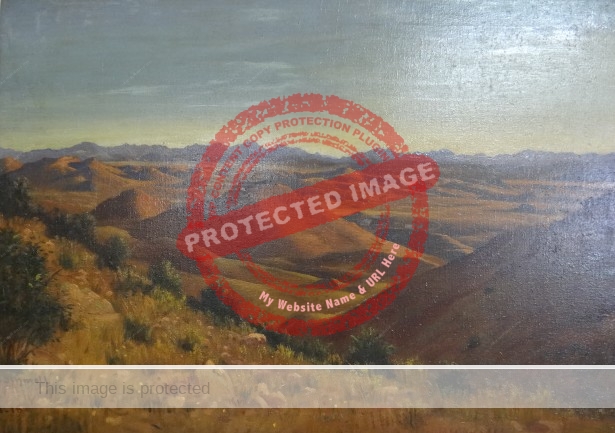

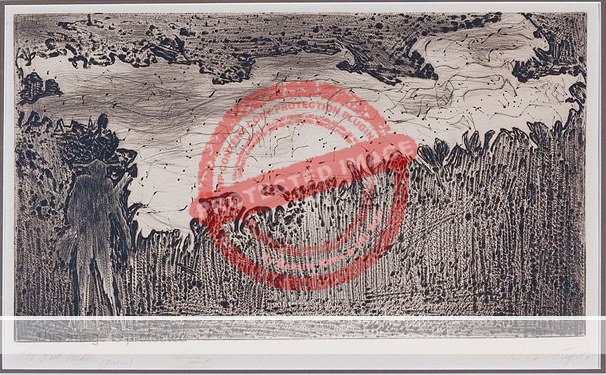

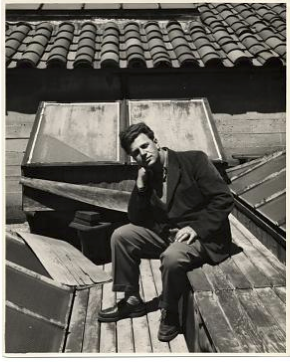

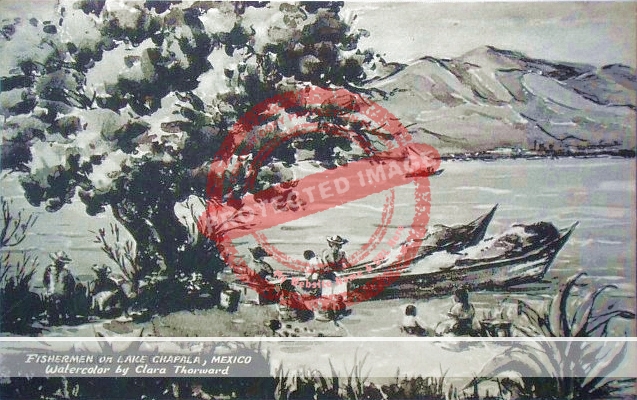

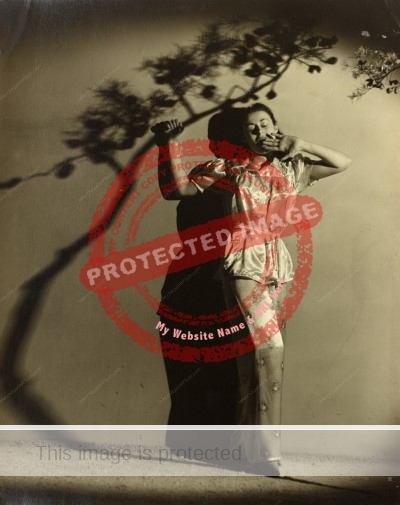

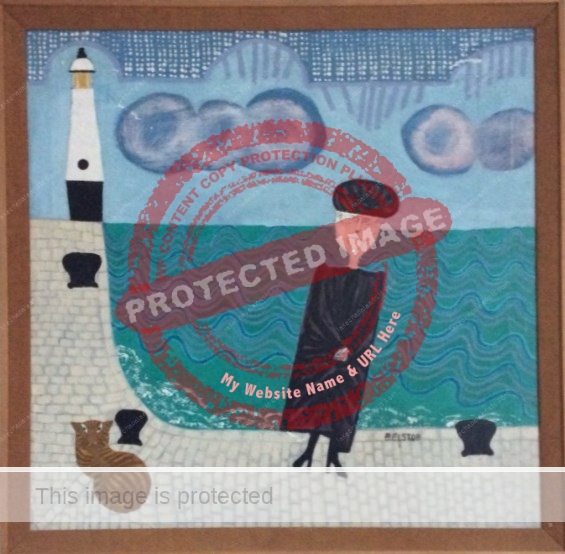

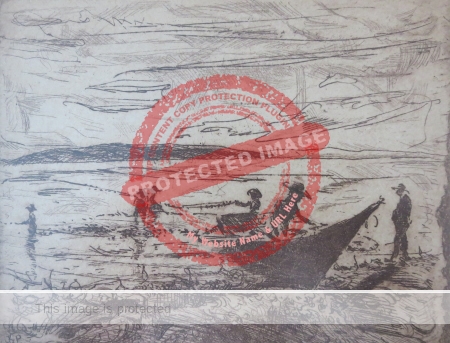

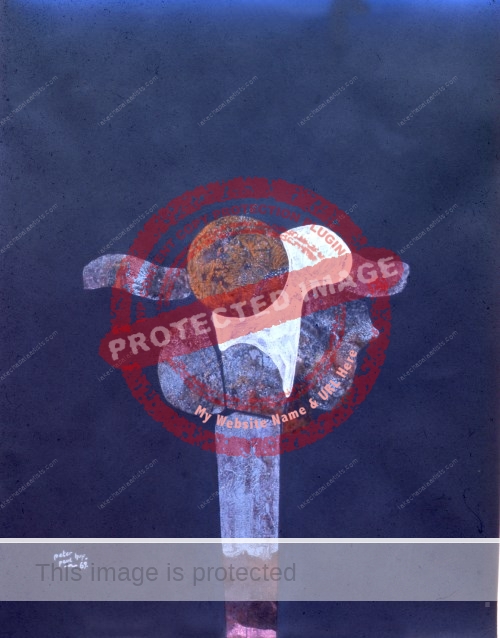

John K Peterson. Chapala Pier. 1968. Reproduced by kind permission of Alan Pattison.

Alan Pattison, who knew the artist well, describes a Peterson painting (above) that he owns and loves: “It is the old marina and pier in Chapala. The guys on the pier are bringing in a net full of fish. … Note the circular movement around the boat – John told me that the guy (whom John knew) was so hungover he could not get the boat out of the marina and was just going in circles. Note also the black sun – John told me that he too was hungover when he was painting the scene and the morning sun was in his eyes and it “pissed him off” hence, he painted it black!”

During the lifetime of the Clique Ajijic collective, Peterson exhibited in their group shows at Villa Monte Carlo in Chapala (March 1975); Galería del Lago, Ajijic (Colón #6; August 1975); the Hotel Camino Real, Ajijic (September 1975); Galería OM, Guadalajara (October 1975); Club Santiago, Manzanillo (October 1975); Akari Gallery, Cuernavaca (February 1976) and the American Society of Jalisco, Guadalajara (February 1976).

Besides these shows, Peterson participated in the “Nude Show” that opened at at Galeria del Lago in Ajijic in February 1976. Other Lakeside artists in this show included John Frost, Synnove (Schaffer) Pettersen, Gail Michel, Dionicio, Georg Rauch and Robert Neathery.

In June 1976, Peterson’s watercolors and engravings featured in a two-person show with the drawings and graphics of Kuiz López at the Villa Monte Carlo in Chapala.

Alan Pattison recalls that the artist’s studio in the early 1970s was on the second floor of a building on the west side of Calle Colón, part-way down towards the lake from the square. Earlier in his life, Peterson had met Ella Fitzgerald and had painted her a couple of times. One of the paintings was “especially whimsical, musical and alive”. He continued to love blues music throughout his life, and usually had blues music playing in the background while he worked.

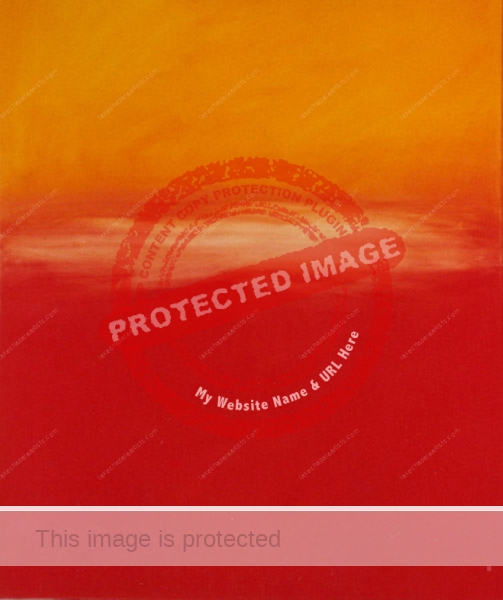

In the late 1970s, Peterson suffered a serious accident, falling from the first floor of his home onto an outdoor sink below. The resultant head trauma caused Peterson to forgo his previous palate of darker tones and his paintings became brighter. He moved away from abstract and impressionist works towards pastels whose predominant colors were bright yellow, green, orange, blue and turquoise.

During his lengthy and prolific artistic career, Peterson had painted murals in San Diego and Los Angeles, and exhibited in New York, Cleveland, Youngstown, Dallas, Phoenix, Portland, San Francisco, San Diego and in many other major cities.

John K. Peterson was one of a kind. His artistic versatility extended to stained glass, fresco, sculpture, water colors, oils and wood blocks. According to Weston, in the small casita near the lake which he rented for $25 a month, he worked six hours a day and completed an average of 30 paintings a month. His generosity to friends and admirers of his work was legendary. In Weston’s words, he “might – and often does – give one of his works to somebody who likes it and can’t afford to buy it.”

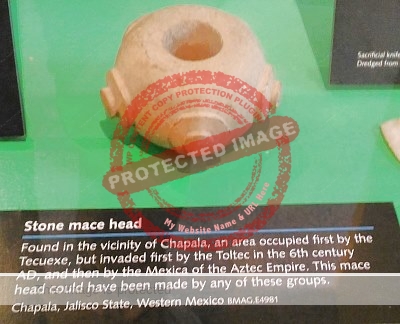

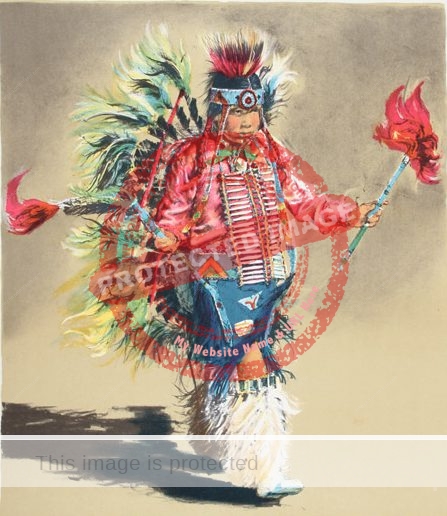

In 1978 and again in 1979, Peterson applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship to undertake an artistic study of indigenous Indian life “to capture the richness of vanishing Indian culture” in Latin America. He was not successful on either occasion.

Peterson’s partner in later life was sculptor Margo Thomas (ca 1917-2011), fondly recalled by his daughter, Monica Porter, as “a very kind and wonderful woman”. Porter and Peterson’s sister, Marion Lee, met Thomas on several occasions in Ajijic. The artist’s relationship with Thomas was not all smooth sailing. On one occasion, after he had completed a large mural for her, the couple had a spat and so he refused to sign it. The couple traveled in Europe together but drifted apart as Peterson began to require more medical care in his final years.

John Kenneth Peterson, one of Ajijic’s larger-than-life characters, made invaluable contributions to the village’s cultural and artistic life and continued to paint until 28 August 1984, when he died of a brain aneurysm in his sleep. [1] A retrospective exhibition of his works was held at “El Lugar”.

Notes:

[1] CR 15 Sep 1984 erroneously gives John K. Peterson’s date of death as 2 September 1984; his Jalisco death certificate states that he died on 28 August 1984.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Karen Bodding, Michael Eager, Tom Faloon, Alan Pattison for sharing with me their memories and knowledge of John K Peterson. Special thanks to Dani Porter-Lansky for providing me with copies of reviews, exhibit invitations, and other published and unpublished documents pertaining to her grandfather’s life, and Monica Porter.

This is an updated version of a post first published on 21 July 2014.

Sources:

- Efanzine – July 2002 – –e*I*3- (Vol. 1 No. 3) July 2002, published and copyright 2002 by Earl Kemp.

- Coronado Eagle and Journal: Number 26 (28 June 1973).

- Guadalajara Reporter: 13 Jan 1968; 3 Feb 1968 ; 15 June 1968; 27 July 1968; 14 Sep 1968; 28 Sep 1968; 24 October 1968; 9 Nov 1968; 16 Dec 1968; 19 April 1969; 26 April 1969; 21 Mar 1970; 3 Apr 1971; 3 June 1972; 1 Jul 1972; 23 Sep 1972; 9 Jun 1973; 10 Nov 1973; 21 June 1975; 15 August 1975; 31 Jan 1976;

- El Informador : 20 April 1969

- Katie Goodridge Ingram. 1976. “Lake Chapala Riviera”, Mexico City News, 20 June 1976, p 13.

- The San Diego Union : 9 March 1952

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.