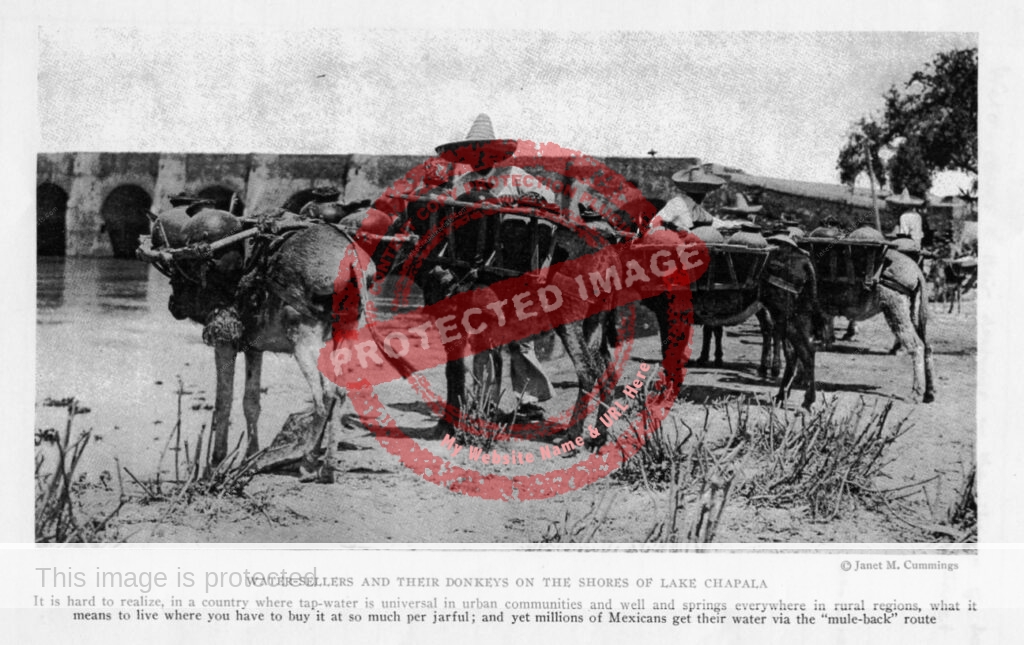

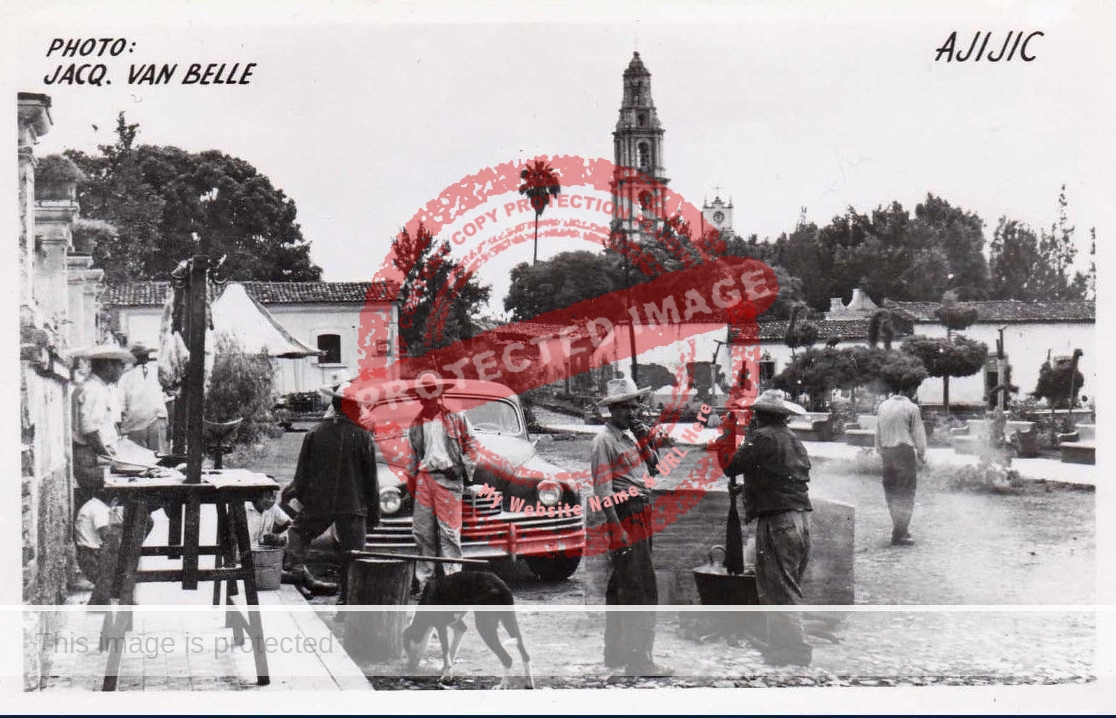

Eunice and Peter Huf are artists who met in Mexico in the 1960s and lived in Ajijic on Lake Chapala for several years, before relocating to Europe with their two sons in the early 1970s.

Eunice Eileen (Hunt) Huf, born 27 February 1933 in Alberta, Canada, can trace her family’s roots back to Switzerland and Germany. Her mother migrated to Canada from Bessarabia in Eastern Europe. Her father was born in Alberta.

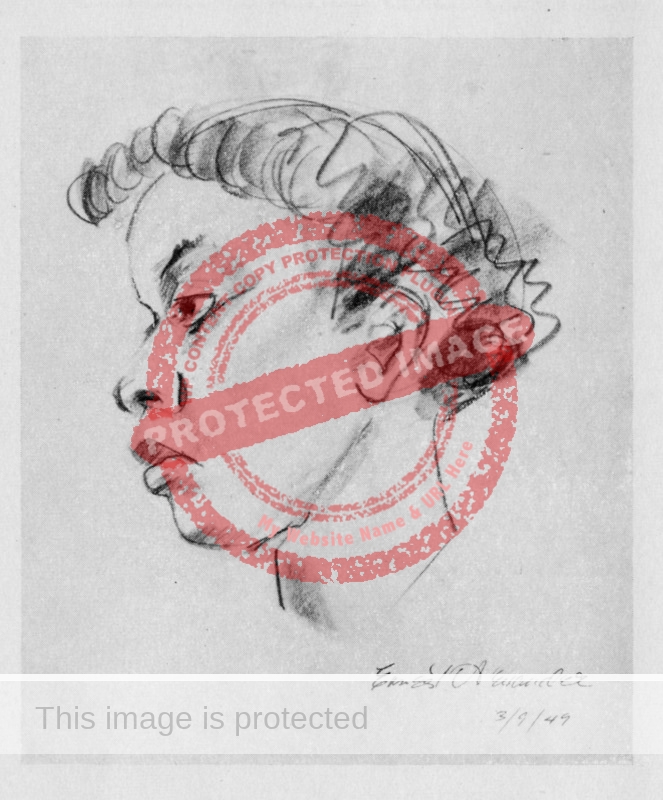

Eunice studied painting for two years in Edmonton, specializing in portraiture. She married young and worked for a couple of years before continuing her art studies at the Vancouver Art School (now the Emily Carr University of Art and Design) where she also honed her skills in photography. She then worked as a freelance artist in Canada and Arizona before deciding to visit Mexico to regroup following the break-down of her first marriage which ended in divorce.

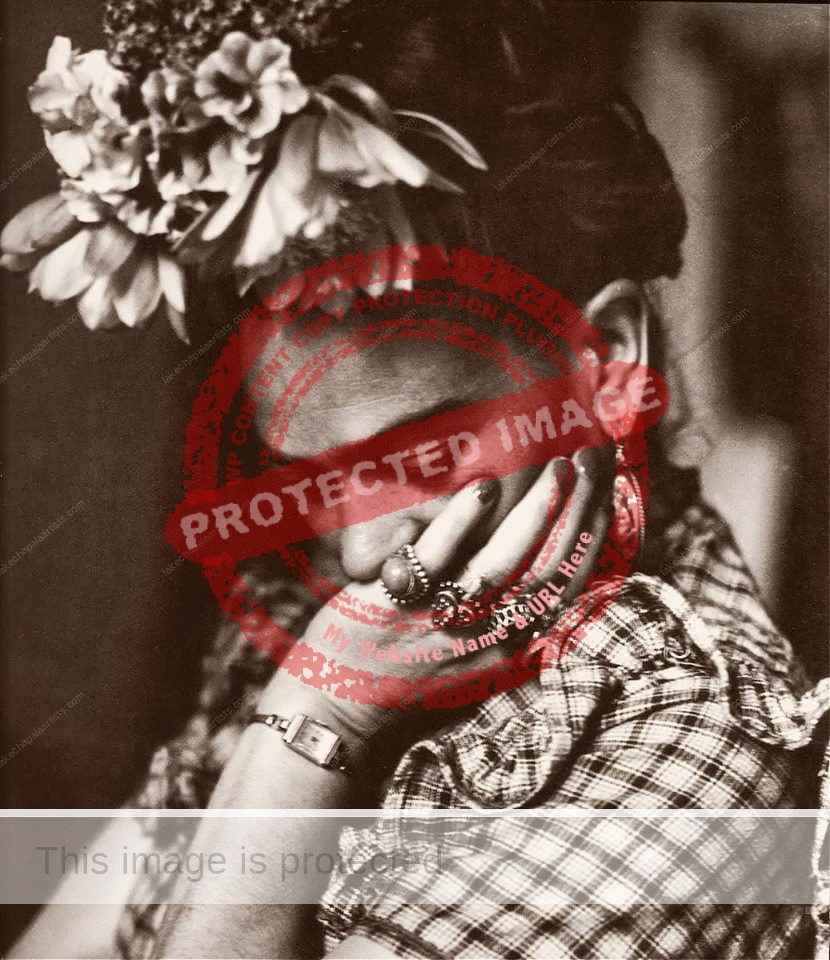

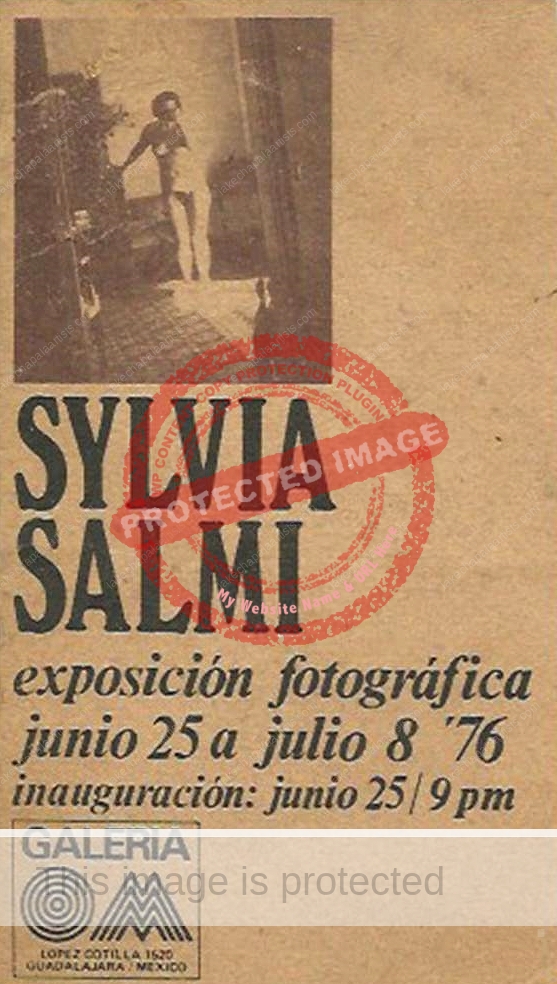

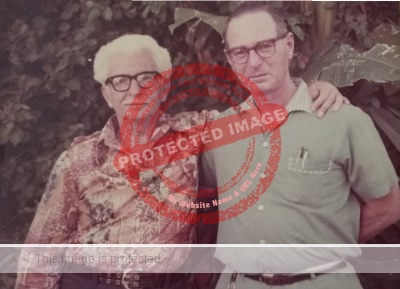

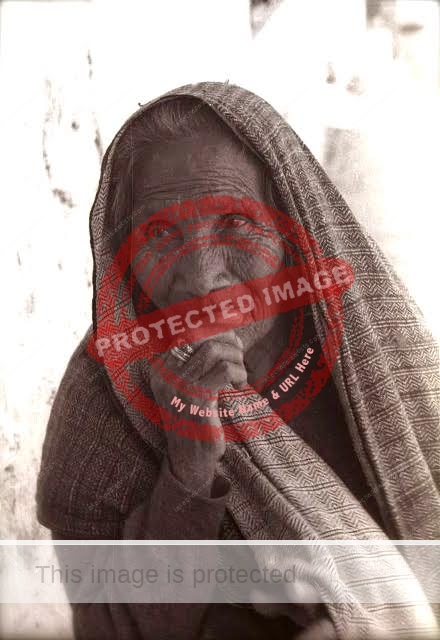

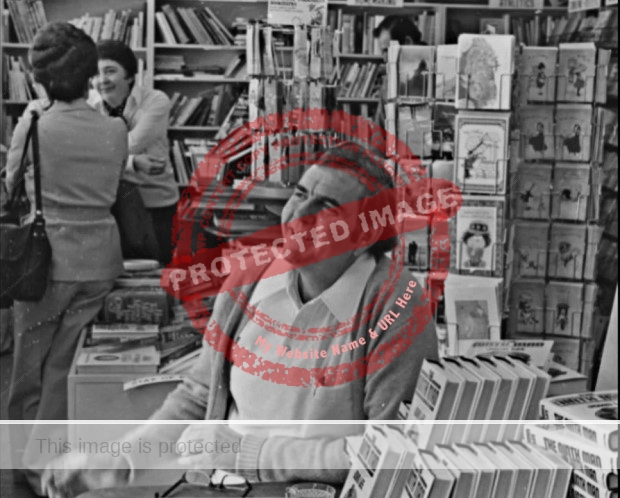

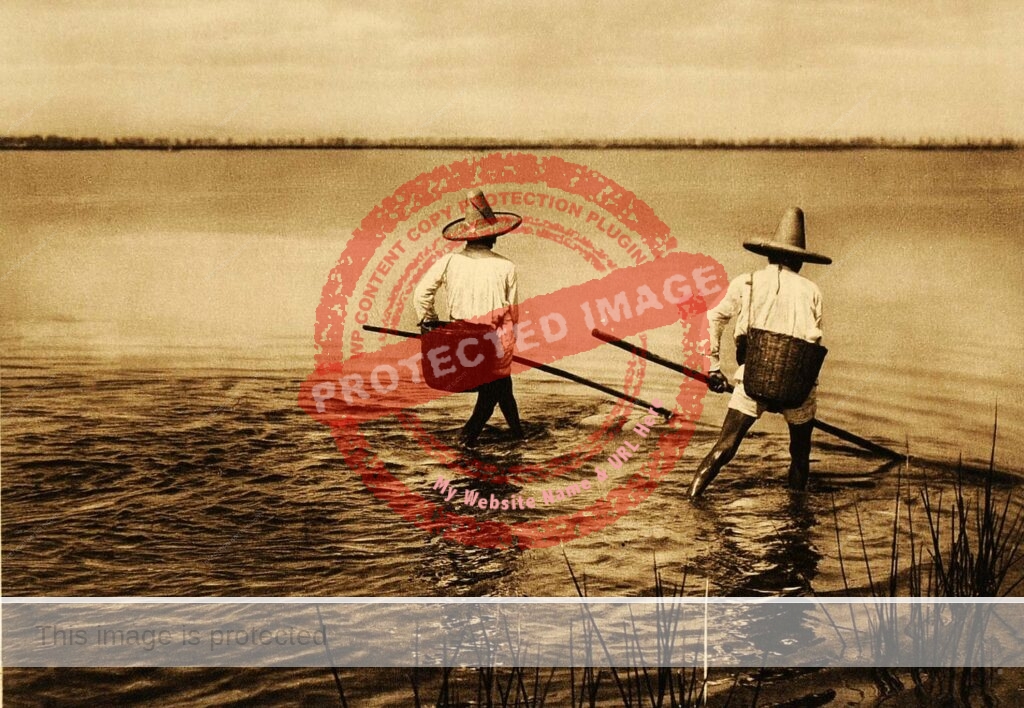

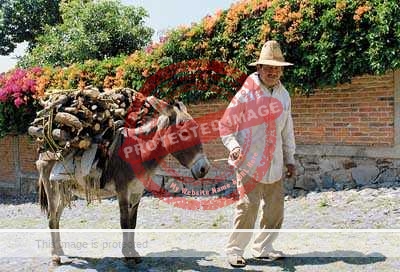

Eunice Huf at Lake Chapala, ca 1968. Photo by Peter Huf. Reproduced by kind permission.

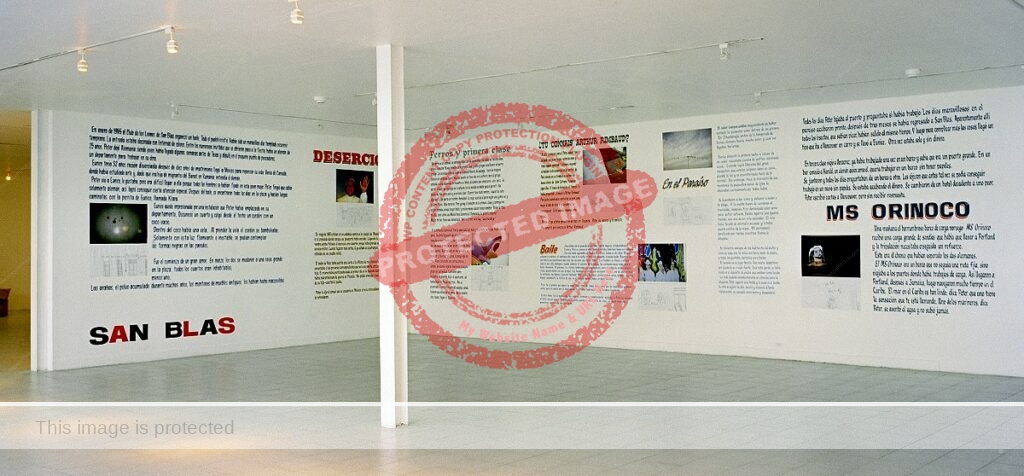

Her visit to Mexico was life-changing. After relaxing and painting for a few weeks in the small tropical town of San Blas on the Pacific Coast, Eunice went to a Sunday night Lion’s Club dance where she met a tall, handsome, German artist, Peter Paul Huf. It was January 1965 and the start of a life-long romance. Forty years later, the Huf’s elder son, Paul “Pablo” Huf, retold the story of this romance in an enthralling art display in Mexico City.

After meeting at the dance, Eunice and Peter spent the next six months together, first in San Blas and then in Oaxaca and Zihuatanejo (Guerrero). It was in San Blas where they first met Jack Rutherford and his family with their vintage school bus, the start of a long friendship. Rutherford had dug the sand away from the walls of an abandoned building in order to display and sell his paintings. In February 1965, Eunice and Peter Huf exhibited together in a group art show on the walls of the then-ruined, roofless, customs house (partially restored since as a cultural center).

After visiting Zihuatanejo, Eunice returned to Vancouver in June 1965, while Peter returned to Europe. They eventually reunited in Amsterdam later that year and traveled to Spain and Morocco from where Eunice continued on to South Africa for a short visit.

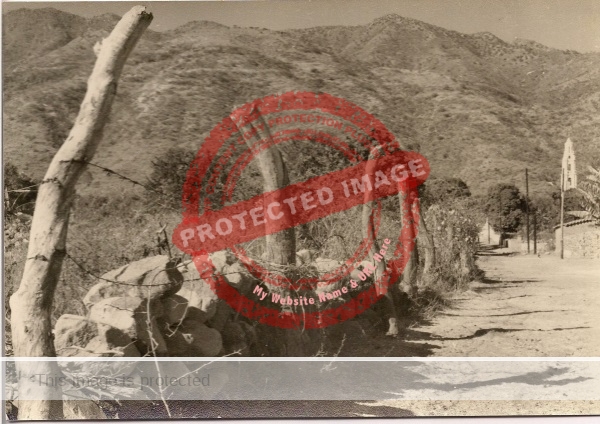

By January 1967 they were back together (this time for good!) and aboard a ship bound for Mexico. After landing in Veracruz, they returned first to San Blas (where they displayed paintings in an Easter exhibition in the former customs house) and then to Ajijic, which the Rutherfords had suggested was a good place to live, paint and sell year-round.

Peter and Eunice Huf married soon after arriving in Ajijic and lived in the village from May 1967 until June 1972. They have two sons: Paul “Pablo” Huf, born in 1967, and Kristof Huf, born in 1971.

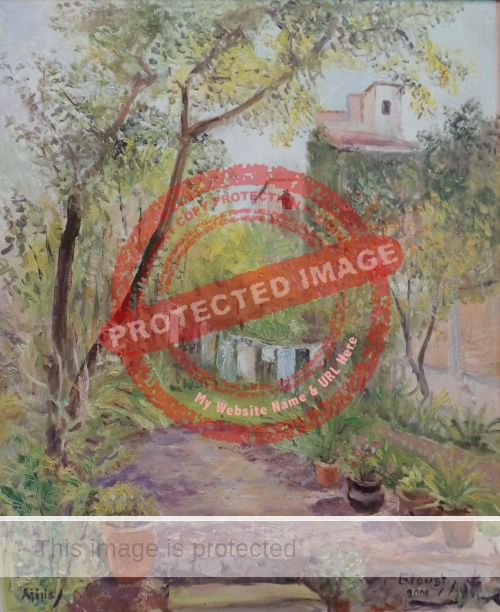

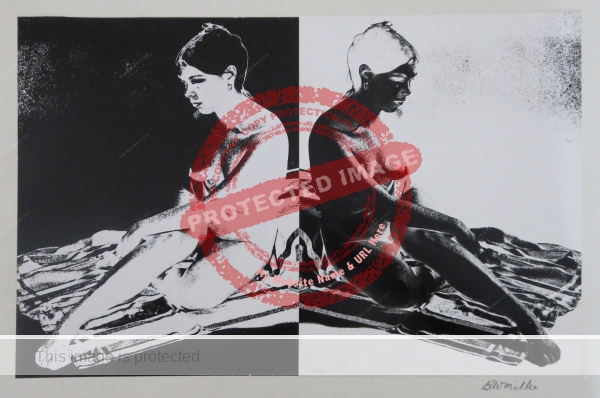

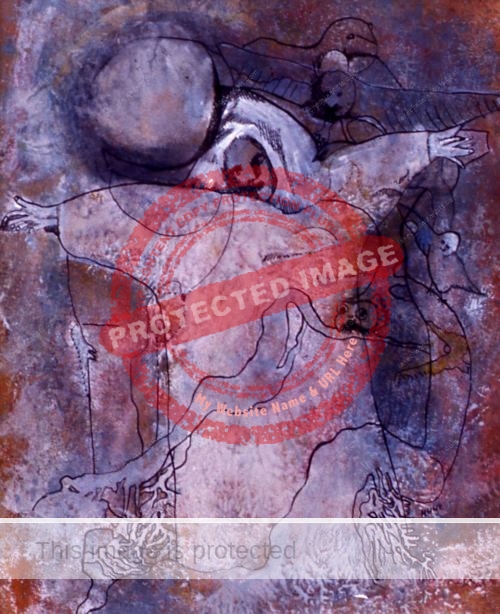

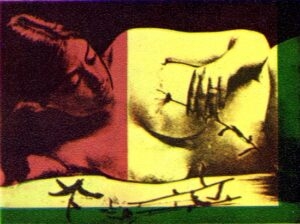

Eunice Hunt: Scarecrow Bride. 1970. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

For almost all her time in Mexico (even after her marriage to Paul Huf), Eunice exhibited as Eunice Hunt, only changing her artistic name to Eunice Huf at about the time the couple left Mexico in 1972 to move first to Andalucia, Spain (1972-1974) and then to Bavaria, Germany.

Both Peter and Eunice Huf regularly exhibited their work in Guadalajara, Tlaquepaque and Ajijic. They also sold artworks from their own studios in Ajijic, located first in a building on Calle Galeana and then at their home on Calle Constitución #30 near the Posada Ajijic hotel. (This building, incidentally, was later occupied by artists Adolfo Riestra and Alan Bowers).

Eunice Huf supplemented the family income by giving private art classes to many people, including former Hollywood producer Sherman Harris, the then manager of the Posada Ajijic. Eunice kept an iguana, that she had borrowed to paint, under her bed, and had a little iguana, too.

Peter and Eunice were founder members of a small collective of artists, known as Grupo 68, that exhibited regularly at the Camino Real hotel in Guadalajara and elsewhere from 1967 to 1971. Grupo 68 initially had 5 members: Peter Huf, Eunice Huf, Jack Rutherford, John K. Peterson and (Don) Shaw (who was known only by his surname). Tom Brudenell was also listed as part of the group for some shows. Jack Rutherford dropped out of the group after a few months, but the remaining four stayed together until 1971.

The exhibitions at the Camino Real hotel began at the invitation of Ray Alvorado, a singer who was the public relations manager of the hotel. Members of Grupo 68 began to exhibit regularly, every Sunday afternoon, in the hotel grounds. Later, they also exhibited inside the hotel at its Thursday evening fiesta.

The Hufs’ first joint show in Ajijic was at Laura Bateman’s gallery, Rincón del Arte, which opened on 15 December 1967, when their firstborn son was barely two months old.

1968 was an especially busy year for the Hufs. They were involved in numerous exhibitions, beginning with one at El Palomar in Tlaquepaque which opened on 20 January. Other artists at this show included Hector Navarro, Gustavo Aranguren, Coffeen Suhl, John Peterson, Shaw, Rodolfo Lozano, and Gail Michael. The Ajijic artists in this group, together with Gail Michael, Jules and Abby Rubenstein, and Jack and Doris Rutherford, began to exhibit at El Palomar every Friday.

In May 1968 the Galeria Ajijic (Marcos Castellanos #15) opened a collective fine crafts show. Eunice and Peter Huf presented “miniature toy-like landscapes complete with tiny figures and accompanying easels” which were popular with tourists, alongside wall-hangings, jewelry and sculptures by Ben Crabbe, Beverly Hunt, Gail Michael, Mary and Hudson Rose, Joe Rowe and Joe Vines.

The next month (June 1968), the Hufs were back in Guadalajara, exhibiting in the First Annual Graphic Arts Show (prints, drawings, wood cuts) at Galeria 8 de Julio in Guadalajara. This show also featured works by John Frost, Paul Hachten , Allyn Hunt, John K. Peterson, Tully Petty, Gene Quesada and Don Shaw. Reviewing the show, Allyn Hunt admired Eunice Hunt’s “Moon Trap”, saying it “has a lyrical, fantasy-like quality”.

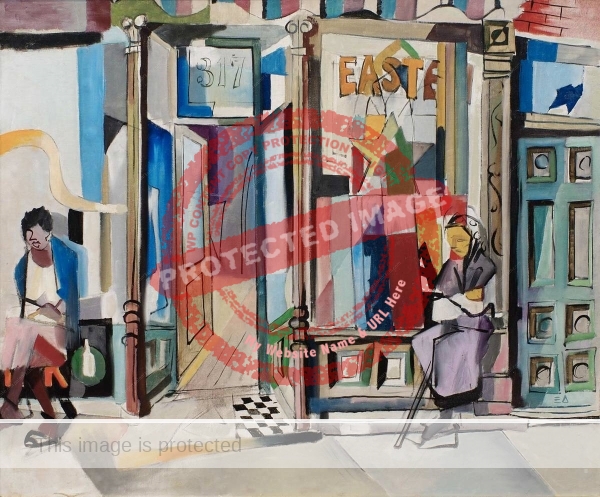

Eunice Hunt: Still llife. 1969. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

The “re-opening” of Laura Bateman’s Rincón del Arte gallery in Ajijic (at Calle Hidalgo #41) in September was accompanied by a group show of 8 painters-Tom Brudenell, Alejandro Colunga, Peter Paul Huf, Eunice Hunt, John K Peterson, Jack Rutherford, Donald Shaw and Coffeen Suhl – and a sculptor: Joe Wedgwood.

At the end of October Eunice Huf held her first solo show in Mexico, showing 40 paintings at the Galeria 8 de Julio in Guadalajara (located at * de Julio #878). The show was one of the numerous art exhibitions in the city comprising the Cultural Program of the International Arts Festival for the XIX Mexico City Olympics. (Her show preceded a solo show of works by Georg Rauch also under the patronage of Señora Holt and the Olympics.)

At the same time as Huf’s solo show, Grupo 68 (listed as Peter Paul Huf, Eunice Hunt, John K Peterson and Shaw) shared the Galería del Bosque (Calle de la Noche #2677) in Guadalajara with José María de Servín. This event was also part of the Olympics Cultural Program.

Towards the end of 1968, the Hufs co-founded a co-operative gallery “La Galería” in Ajijic, located on Calle Zaragoza at its intersection with Juarez, one block west of El Tejaban. On Friday 13 December 1968, the month-long group show for the “re-opening” of La Galería in Ajijic was entitled “Life is Art”. It consisted of works by Tom Brudenell, Alejandro Colunga, John Frost, Paul Hachten, Peter Paul Huf, Eunice Hunt, John K Peterson, Jack Rutherford, José Ma. De Servin, Shaw, Cynthia Siddons (now Cynthia Luria), and Joe Wedgwood. Art lovers attending gallery openings at this time were often served a tequila-enriched pomegranate ponche alongside snacks such as peanuts.

Somehow, in this crowded year, the Hufs also managed to fit in an exhibition at Redwood City Gallery in California.

In February 1969, Eunice and Peter Huf joined with (Don) Shaw to exhibit at the 10th floor penthouse Tekare Restaurant at Calle 16 de Sept. #157, in Guadalajara. This location has fame as the first place where jazz was played in Guadalajara. Later that year, Eunice Huf had a showing at the co-operative La Galería in Ajijic.

“Grupo 68” (Eunice and Peter Huf, Don Shaw and John K Peterson) held a showing of works at The Instituto Aragon (Hidalgo #1302) in Guadalajara in June 1969.

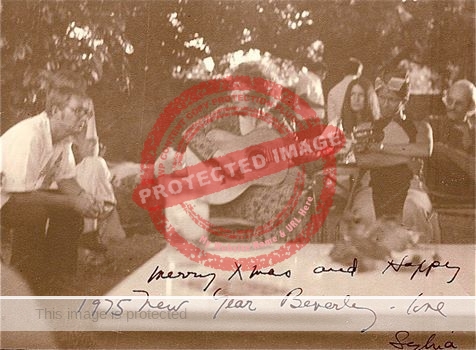

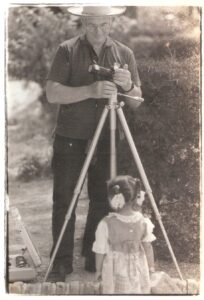

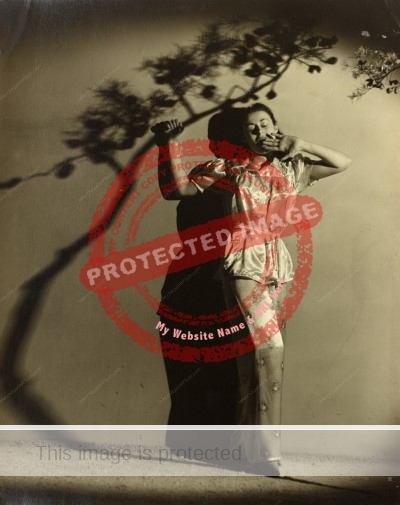

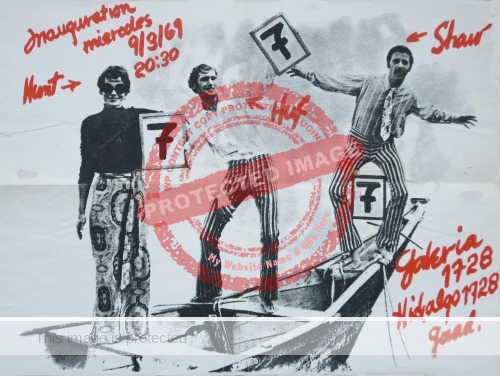

7-7-7 show (Hunt, Huf, Shaw), 1969. (Photo by John Frost)

Three of these artists (the Hufs and Shaw) held another show shortly afterwards in Guadalajara at Galeria 1728 (Hidalgo #1728). That gallery was owned by Jose Maria de Servin and the show was entitled 7-7-7. It featured seven works by each artist with the promotional material featuring a pose by the three artists emulating the Olympic scoring system.

The following year (1970), an Easter Art Show which opened at the restaurant-hotel Posada Ajijic on 28 March featured works by Eunice and Peter Huf, John Frost, John K. Peterson, Bruce Sherratt and Lesley (Maddox) Sherratt.

In June 1970, Eunice Huf’s work was included in a group showing at the Casa de la Cultura Jalisciense in Guadalajara. Other Lakeside artists with works in this show included Peter Huf, Daphne Aluta, Mario Aluta, John Frost, Bruce Sherratt and Lesley Jervis Maddock (aka Lesley Sherratt).

In May 1971, both Peter Huf and Eunice Hunt were among those exhibiting at a Fiesta de Arte in Ajijic, held at a private home. More than 20 artists took part in that event, including Daphne Aluta; Mario Aluta; Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; Tom Faloon; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Gail Michael (Michel); Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; John K. Peterson; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; Robert Snodgrass; and Agustín Velarde.

A review of the Hufs’ “Farewell Show” at El Tejaban restaurant in Ajijic in May 1972 congratulated them on their contribution to the local art scene, saying that their “steady flow of exceptional paintings has been a bright force in the art community of Jalisco for the past six years.”

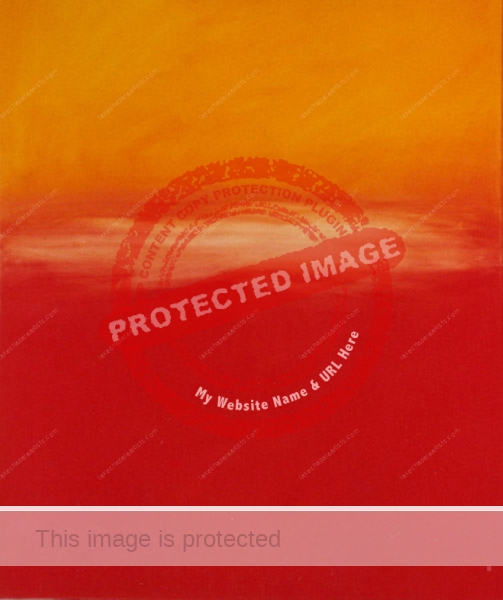

Eunice Huf. Red with clouds. 1994. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

Shortly before leaving Mexico, the Hufs illustrated a short 32-page booklet entitled Mexico My Home. Primitive Art and Modern Poetry With 50 easy to learn Spanish words and phrases. For all children from 8 to 80, published in Guadalajara by Boutique d’Artes Graficas in 1972. The poems in the booklet were written by Ira N. Nottonson, who was also living in Ajijic at the time. The illustrations in the book are Mexican naif in style, whereas their own art tended to be far more abstract or surrealist.

Eunice and Peter Huf left Mexico in the summer of 1972 with every intention of returning, but never did, despite making plans in early 1976 for shipping their recent works from Germany to Ajijic for a show at Jan Dunlap’s Wes Penn Gallery. According to organizers, the artists wanted to return to Ajijic permanently. It appears that this show never actually took place, owing to complications of logistics and customs regulations.

On moving to Europe, the Hufs lived near Nerja, in Andalucia, southern Spain, for a time, before settling in 1974 near Peter’s hometown of Kaufbeuren in the Allgäu region of southern Germany. The couple now have studios in the house where he was born in Kaufbeuren. Their work, known for the use of bright colors, has appeared regularly in exhibitions over the years, with both artists winning many awards along the way.

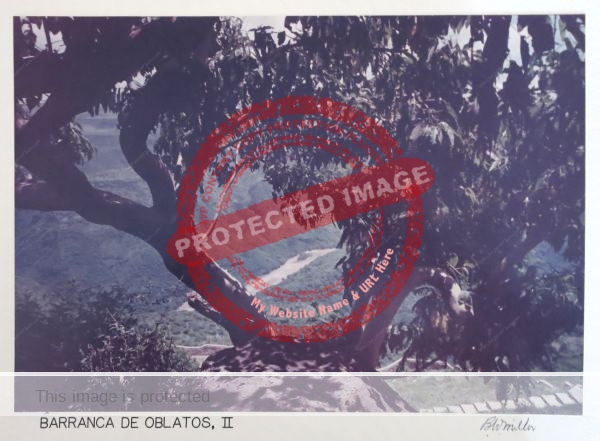

Eunice Huf. Excerpt from “Taking time out”.

Eunice Huf’s lengthy artistic career has continued unabated. The long list of exhibitions in which her work has featured includes: University Exhibit, Edmonton (1962); City Gallery Vancouver (1963); Downtown Gallery, Tucson, Arizona (1964); Stellenbush, South Africa (1966); Galeria Aduana, San Blas, Mexico (1966); Rincon del Arte, Ajijic (1967); Galeria 8 de Julio, Guadalajara (1968); Redwood City Gallery, California (1968); La Galeria, Ajijic (1969); Tekare, Guadalajara (1969); El Instituto Aragon, Guadalajara (1970); El Tejabán, Ajijic (1971); El Rastro, Marbella, Spain (1972); followed by many other exhibitions in Spain and across Germany. Huf was represented by Munich-based Galeria Hartmann in International Art Fairs in Cologne and Basel.

Both Eunice and Peter Huf were regulars until 2013 at Munich’s Schwabing Christmas Market, held annually since 1975.

Unlike her husband’s works which are usually painted in acrylics, Eunice Huf prefers oils and line drawings. She has produced several somewhat whimsical, exquisite, little books featuring her deceptively simple line drawings, but also does larger works, including paintings described by one reviewer as shaped by the open expanses of her native Canadian prairies.

Eunice Huf died on 12 February 2022, shortly before her 89th birthday, and while working on drawings and paintings for a solo exhibition at the Museum of the City of Füssen (Museum der Stadt Füssen) titled “Allgäu – small oils and drawings.” The exhibition was held posthumously in the summer of 2022 and marked sixty years of exhibitions in which Eunice Huf’s varied and ever-evolving work was on show to the delight of art lovers.

Acknowledgment

I am very grateful to Eunice and Peter Huf for their warm hospitality during a visit to their home and studio in October 2014 which has led to a lasting friendship. Their archive of photos and press clippings from their time in Mexico proved invaluable, as was their encouragement and their memories of people and events of the time.

Sources:

- Ira N. Nottonson. 1972. Mexico My Home. Primitive Art and Modern Poetry With 50 easy to learn Spanish words and phrases. For all children from 8 to 80. (Guadalajara, Mexico: Boutique d’Artes Graficas. 1972. 32pp, short poems illustrated with 16 paintings by Eunice and Peter Huf.

- Guadalajara Reporter : 9 Dec 1967; 13 Jan 1968; 3 Feb 1968; 25 May 1968; 15 June 1968; 21 Mar 1970; 13 June 1970; 3 Apr 1971; 20 Nov 1971; 20 May 1972; 28 Feb 1976

- El Informador (Guadalajara): 5 Jun 1970

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.