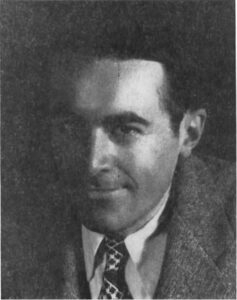

Artist and writer Allyn Hunt lived in the Lake Chapala area from the mid-1960s to 2022. Hunt was the owner and editor for many years of the weekly English-language newspaper, the Guadalajara Reporter. His weekly columns for the newspaper quickly became legendary. Hunt’s wife, Beverly (1936-2024), also worked at the Guadalajara Reporter and later ran a real estate office and Bed and Breakfast in Ajijic.

Hugh Allyn Hunt was born in Nebraska in 1931. His mother, Ann, was granted a divorce from her husband J. Carroll Hunt, the following year. Allyn Hunt grew up in Nebraska before moving to Los Angeles as a teenager.

He studied advertising and journalism at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles, where he took a creative writing class under novelist and short story writer Willard Marsh. Marsh had known Ajijic since the early 1950s and later wrote a novel set in the village.

At USC, Hunt was associate editor of Wampus, the USC student humor magazine, and according to later bios he also became managing editor of the university newspaper, the Daily Trojan.

After graduating, Hunt worked as public relations representative for Southern Pacific Railroad, and edited its “house organ”, before becoming publicity director and assistant to director of advertising for KFWB radio in Los Angeles. Hunt also worked, at one time or another, as a stevedore, photographer’s model, riding instructor and technical writer in the space industry.

Living in Los Angeles gave Hunt the opportunity to explore Tijuana and the Baja California Peninsula. As he later described it, he became a frequent inhabitant of Tijuana’s bars and an aficionado of Baja California’s beaches and bullfights.

Hunt and his [third] wife, Beverly, moved to Mexico in 1963, living first in Ajijic and then later in the mountainside house they built in Jocotepec. They would remain in Mexico, apart from two and a half years in New York from 1970 to 1972.

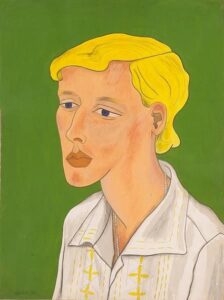

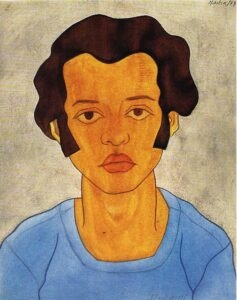

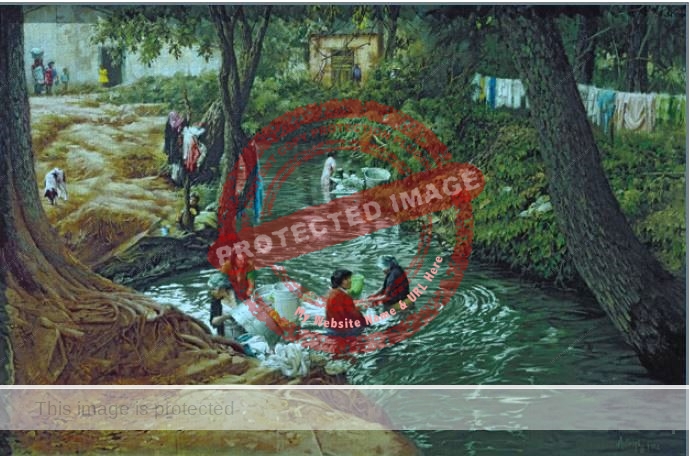

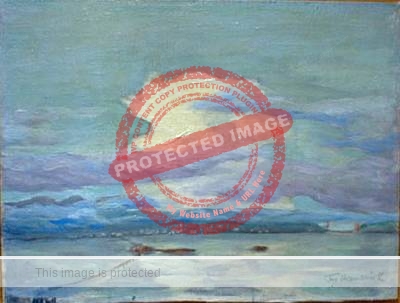

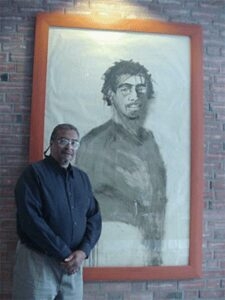

Winnie Godfrey. Portrait of Allyn & Beverly Hunt, (oil, ca 1970)

This portrait of Allyn and Beverly Hunt was painted by Winnie Godfrey who subsequently became one of America’s top floral painters.

In their New York interlude, Hunt wrote for the New York Herald and the New York Village Voice, and apparently also shared the writing, production and direction of a short film, released in 1972, which won a prize at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival in Germany and was shown on European television. (If anyone knows the title of this film, or any additional details about it, please get in touch!)

When the Hunts returned from New York, they decided to build a house in Nextipac, in Jocotepec. They moved into their house, “Las Graciadas”, towards the end of 1973. The following year, they agreed to purchase the Guadalajara Reporter. They became owners and editors of the weekly newspaper in 1975 and Hunt would be editor and publisher of the Guadalajara (Colony) Reporter for more than 20 years. Hunt’s numerous erudite columns on local art exhibitions have been exceedingly useful in my research into the history of the artistic community at Lake Chapala.

As a journalist, Hunt also contributed opinion columns to the Mexico City News for 15 years, and to Cox News Service and The Los Angeles Magazine.

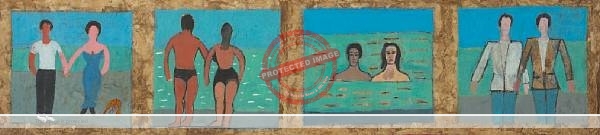

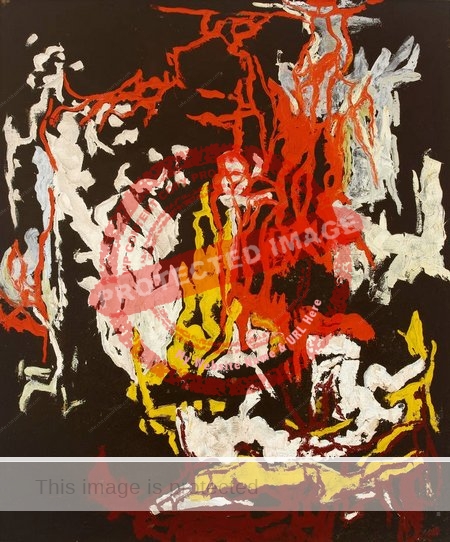

As an artist, Hunt exhibited numerous times in group shows in Ajijic and in Guadalajara. For example, in April 1966, he participated in a show at the Posada Ajijic that also featured works by Jack Rutherford; Carl Kerr; Sid Adler; Gail Michel; Franz Duyz; Margarite Tibo; Elva Dodge (wife of author David Dodge); Mr and Mrs Moriaty and Marigold Wandell.

The following year Hunt’s work was shown alongside works by several Guadalajara-based artists in a show that opened on 15 March 1967 at “Ruta 66”, a gallery at the traffic circle intersection of Niños Héroes and Avenida Chapultepec in Guadalajara.

In March-April 1968, Hunt’s “hard-edged paintings and two found object sculptures” were included in an exhibit at the Galería Ajijic Bellas Artes, A.C., at Marcos Castellanos #15 in Ajijic. (The gallery was administered at that time by Hudson and Mary Rose).

Later that year – in June 1968 – Hunt showed eight drawings in a collective exhibit, the First Annual Graphic Arts Show, at La Galeria (Ocho de Julio #878) in Guadalajara. That show also included works by Tom Brudenell, John Frost, Paul Hachten, Peter Huf, Eunice Hunt, John K. Peterson, Eugenio Quesada and Tully Judson Petty.

The following year, two acrylics by Hunt were chosen for inclusion in the Semana Cultural Americana – American Artists’ Exhibit at the Instituto Cultural Mexicano Norteamericano de Jalisco in Guadalajara (at Tolsa #300). That show, which opened in June 1969, featured 94 works by 42 U.S. artists from Guadalajara, the Lake area and San Miguel de Allende.

The details of any one-person art shows of Hunt’s works in the U.S. or Mexico remain elusive. (Please get in touch if you can supply details of any other shows in which Allyn Hunt’s art was represented!)

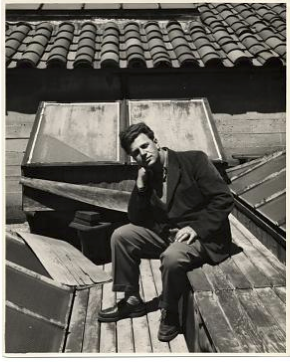

In the early-1960s, Hunt was at least as keen to become an artist as a writer. Rex Oppenheimer later recalled in an article for Steel Notes Magazine that when he visited his father in Zapopan (on the outskirts of Guadalajara) in 1965,

“Among the first of my father’s friends that I met were Allen and his wife Beverly. Allen was an artist. He looked like a beatnik or incipient Hippie and had a very cool house out in Ajijic near Lake Chapala. After touring the house and taking in his artwork, we went up on the roof. I don’t remember the conversation, but there was a great view out over the lake, and I got totally smashed on Ponche made from fresh strawberries and 190 proof pure cane alcohol.”

Despite his early artistic endeavors, Hunt is much better known today as a writer of short stories. His “Acme Rooms and Sweet Marjorie Russell” was one of several stories accepted for publication in the prestigious literary journal Transatlantic Review. It appeared in the Spring 1966 issue and explores the topic of adolescent sexual awakening in small-town U.S.A. It won the Transatlantic’s Third Annual Short Story Contest and was reprinted in The Best American Short Stories 1967 & the Yearbook of the American short story, edited by Martha Foley and David Burnett. Many years later, Adam Watstein wrote, directed and produced an independent movie of the same name. The movie, based closely on the story and shot in New York, was released in 1994.

One curiosity about that Spring 1966 issue of Transatlantic Review is that it also contained a second story by Hunt, entitled “The Answer Obviously is No”, written under the pen name “B. E. Evans” (close to his wife’s maiden name of Beverly Jane Evans). The author’s notes claim that “B. E. Evans was born in the Mid-West and lived in Los Angeles for many years where he studied creative writing under Willard Marsh. He has lived in Mexico for the past year and a half. This is his first published story.”

Later stories by Hunt in the Transatlantic Review include “Ciji’s Gone” (Autumn 1968); “A Mole’s Coat” (Summer 1969), which is set at Lake Chapala and is about doing acid “jaunts”; “A Kind of Recovery” (Autumn-Winter 1970-71); “Goodnight, Goodbye, Thank You” (Spring-Summer 1972); and “Accident” (Spring 1973).

Hunt was in exceptionally illustrious company in having so many stories published in the Transatlantic Review since his work appeared alongside contributions from C. Day Lewis, Robert Graves, Alan Sillitoe, Malcolm Bradbury, V. S. Pritchett, Anthony Burgess, John Updike, Ted Hughes, Joyce Carol Oates, and his former teacher Willard Marsh.

Hunt also had short stories published in The Saturday Evening Post, Perspective and Coatl, a Spanish literary review.

At different times in his writing career, Hunt has been reported to be working on “a novel set in Mexico”, “a book of poems”, and to be “currently completing two novels, one of which is set in what he calls the “youth route” of Mexico-Lake Chapala, the Mexico City area, Veracruz, Oaxaca and the area north and south of Acapulco”, but it seems that none of these works was ever formally published.

Very few of Hunt’s original short stories can be found online, but one noteworthy exception is “Suspicious stranger visits a rural tacos al vapor stand,” a story that first appeared in the Guadalajara Reporter in 1995 and was reprinted, with the author’s permission, on MexConnect.com in 2008.

Allyn Hunt, artist, writer, editor and publisher, died in a San Juan Cosalá nursing home at the age of 90 on 3 February 2022.

Sources:

- Broadcasting (The Business Weekly of Radio and Television), May 1961.

- Daily Trojan (University of Southern California), Vol. 43, No. 117, 21 April 1952.

- Martha Foley and David Burnett (eds). The Best American Short Stories 1967 & the Yearbook of the American short story.

- Guadalajara Reporter. 2 April 1966; 12 March 1967; 27 April 1968; 15 June 1968; 27 July 1968; 5 April 1975

- The Lincoln Star (Nebraska). 15 August 1932.

- Rex Maurice Oppenheimer. 2016. “Gunplay in Guadalajara“. Steel Notes Magazine.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether by email or comments feature.

He is included in this on-going series of profiles because in 1992, he self-published a 48-page booklet entitled Lake Chapala: A literary survey; plus an historical overview with some personal observations and reflections of this lakeside area of Jalisco, Mexico. The book was dedicated to

He is included in this on-going series of profiles because in 1992, he self-published a 48-page booklet entitled Lake Chapala: A literary survey; plus an historical overview with some personal observations and reflections of this lakeside area of Jalisco, Mexico. The book was dedicated to

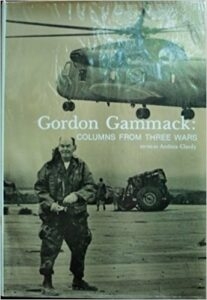

During one of several visits to Korea during the Korean War, Gammack witnessed the first exchange of sick and wounded prisoners of war. He secured an exclusive radio and TV interview with Iowan Richard Morrison, the first American soldier released.

During one of several visits to Korea during the Korean War, Gammack witnessed the first exchange of sick and wounded prisoners of war. He secured an exclusive radio and TV interview with Iowan Richard Morrison, the first American soldier released.