George Adin Ballou was born in Madrid, Spain, on 21 November 1927, and died in May 1986. By the age of 21, according to an article in the Amarillo Daily News, Ballou had already completed several books, including, “a 500-page work on the artist-tourist colony at Lake Chapala”, with the working title of Ajijic. Sadly, there is no record of him ever publishing this or any other book and the manuscript appears to be lost for ever.

UPDATE TO UPDATE (January 2025): Unfortunately, the anonymous friend of George Ballou, who contacted me regarding his Ajijic manuscript, did not reestablish contact with me after their initial message in 2018.

UPDATE (23 June 2018): It has been brought to my attention that George Ballou self-published at least two novels and one travel book which were sold in Greenwich Village, New York. And, even more excitingly, a copy of his book about Ajijic apparently still exists! I am hoping to learn more about this book (and be able to greatly improve on this short biography) within the next few months, so please watch this space!

Who was George Ballou and how did he come to write a book about Ajijic?

George was the son of Harold Ballou (1898-1981), a journalist then working for the American News Service, and author Jenny Dubin Ballou (ca 1903-ca 1948), known in the family as Genia. They met as undergraduates at Cornell University. (She is also sometimes called Eugenia Ballou or Jenny Iphigenia Ballou, the latter variant appearing in a Time magazine review of one of her books.) Jenny was born in Russia in about 1903, and moved to the U.S. at the age of three. She wrote two well-received works, both published in New York: Spanish Prelude (1937) and Period Piece: The Life and Times of Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1940).

“Café Revolutionaries”, a chapter from Spanish Prelude, was chosen in 2007 for inclusion in Barbara Probst Solomon’s literary collection, The Reading Room/7. In her introduction, Solomon writes that,

“When Federico García Lorca returned from Puerto Rico to New York en route to Spain in 1930 and wasn’t able to leave the ship due to a lapsed visa, [Genia] Ballou was among the small group of intellectuals invited to a small party given in his honor aboard the ship.” She also points out that “In the 1930s she [Ballou] wrote for The Florin Magazine, whose contributors included Aldous Huxley, Herbert Read and Stephen Spender.”

George’s middle name, “Adin”, was in honor of his illustrious ancestor, Adin Ballou, who was a passionate anti-slavery advocate in the 1840s and the founder of a utopian community in Massachusetts.

George spent his early childhood in Spain, where his parents were working at the time. He was barely 6 months old when they first returned to the U.S. for a visit, arriving in New York on 5 June 1928 from Barcelona on board the “Manuel Arnus”. The family returned to New York again on 24 December of the following year, aboard the “Leviathan” which had sailed from the port of Cherbourg, France. The passenger manifest lists their New York address as 221 Dekals Ave, Brooklyn, and they were still living in Brooklyn at the time of the 1930 U.S. Census.

As is evident from Jenny Ballou’s Spanish Prelude, the family spent about four more years in Spain in the early 1930s before relocating back to North America. By the time of the 1940 U.S. Census, they were living in in Montgomery, Maryland.

George Ballou completed his high school education at The Putney School, a progressive independent high school in Vermont. He never shied away from physical work and was strongly built despite being not very tall, about 5′ 6″. By coincidence, two long-time Ajijic residents – John Kirtland Goodridge and his brother Geoffrey Goodridge (better known as the flamenco guitarist “Azul”) – also attended The Putney School, albeit about a decade later.

George and his parents were all fluent in Spanish and visited Mexico (including Lake Chapala) for an extended stay, presumably in the early 1940s, though the exact timing is unclear.

George developed a deep, lifelong interest in zoology. He was both passionate and knowledgeable about all manner of animals. At various times, Ballou supplied specimens of mammals, birds and reptiles to zoos in Philadelphia, Washington, and New York, including specimens collected in the jungles of southern Mexico, specifically in the state of Campeche. He is thanked in the Smithsonian annual report for the year ended June 1945 for having donated “a short-tailed shrew, two diamond-back rattlesnakes, two cottonmouth moccasins, six black snakes, cotton rat, mud snake, six garter snakes, two indigo snakes, two blue racer snakes, chicken snake, turkey vulture, five deer mice [and a], meadow mouse.” Ten years later, in the 61st Annual Report of the New York Zoological Society, in 1956, Ballou is listed as the donor of “spiny mice… together with a Palestine Long-eared Hedgehog”.

Immediately after the end of the second world war, Harold Ballou was appointed chief of the European Press section of the United Nations, based in Geneva, Switzerland. At his father’s insistence, George postponed his entry to the University of New Mexico, and accompanied the family to Switzerland, where he took some classes in anthropology at the University of Geneva. Serendipity intervened. Genia, his mother, needed someone to type her latest manuscript (a memoir or autobiography) and gave the job to Anna Barbara Morgenthaler, one of George’s fellow students. Barbara, as she is known in the family, was multilingual, multi-talented and exceptionally well-educated. A few years older than George (she was born in 1924), she also liked animals and zoology, so it was little surprise that they quickly became close friends.

Sadly, Genia, barely in her forties, died from cancer before the manuscript could be published. This was a devastating blow to George. An only child, he had been very close to her all his life. (Harold, who went on to work for the Pan American Health Organization, remarried in 1950; his second wife was Esther Williamson Ballou, a musician and composer).

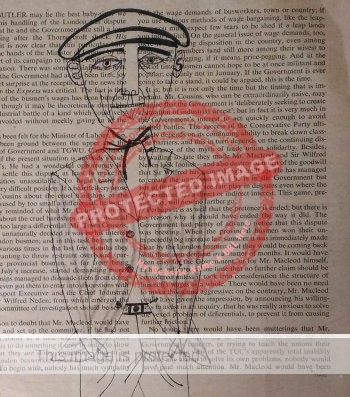

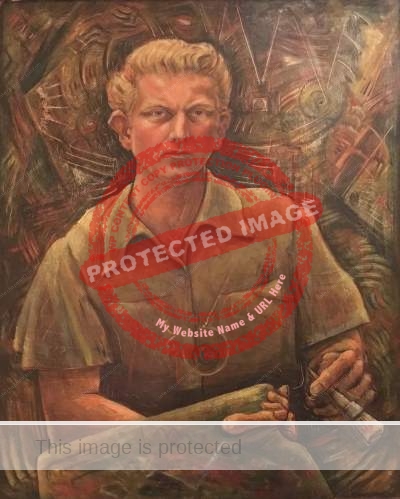

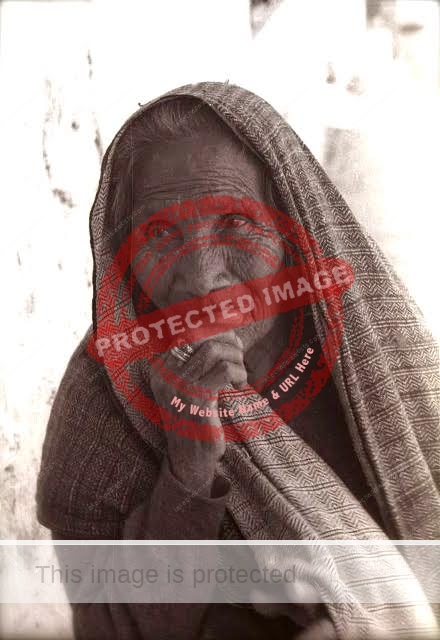

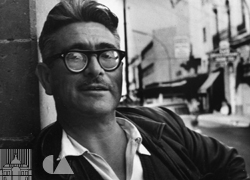

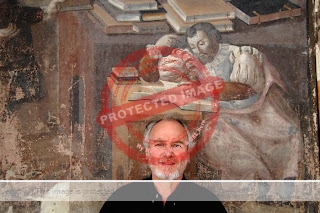

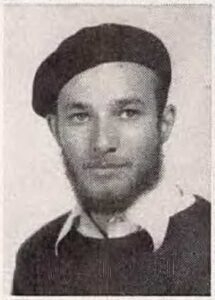

George Ballou (1950 UNM Yearbook)

George and Barbara continued their studies at the University of Geneva until 1948, when his father moved to Egypt as head of the Arab Refugee Commission. (Five years later, Harold Ballou was in Washington D.C. as the Public Information Officer of the Western Hemisphere Regional Office of the World Health Organization.)

By February 1949, George was in the U.S. and about to return to classes at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque. (This move, too, was apparently at his father’s insistence!) Clearly, prior to this, George must have spent sufficient time in Ajijic to research and write his manuscript, though the details of his trip or trips remain elusive.

The Amarillo Daily News article mentions “a copious diary kept of his travels”, and other completed manuscripts, including Too Much Zoo for Mama (a 300-page volume about animals he has collected), Themanop or the Man from Another Planet and The Whole Was His Classroom, as well as several short stories. None of these works was ever published, though Ballou does appear to have published at least two short stories a decade later in Dude magazine: “Slavery Can Be Beautiful” (1957) and “The World’s Best Skier” (1958).

Barbara had accompanied George to New Mexico in 1949 and taken a job as secretary for the New Mexico Society for Crippled Children. According to their son, David Cameron, the social mores of the period meant it was not acceptable for the couple to live under the same roof while unmarried. As a result, his parents decided to marry (in Bernalillo, New Mexico, registry office in 1949) but only on condition that neither would oppose a divorce if their partner later wanted to marry someone else.

Later that same year (1949) the young couple traveled to the newly established state of Israel and spent a month in two kibbutzim.

By the summer of 1950, Barbara was pregnant and the couple had moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, where Barbara worked as secretary for the B’nai B’rith Youth Organization. The New Mexico Lobo, published by the University of New Mexico, included the following paragraph: “Last year’s wayfaring stranger at UNM, Mr. George Ballou, has settled down in Greensboro, N.C. with his wife, a possum, a skunk, and two goldfish. The Ballous made the furniture in their little love nest.”

Six months later, George and Barbara returned to Zürich and their son, David, arrived on Easter Sunday: 25 March 1951. During their time in Switzerland, George’s mental health was fragile. When Barbara and George went to Casablanca, Morocco, in 1953, they left their infant son with his maternal grandparents in Höngg for a year. Barbara worked as a translator at the American airbase in Casablanca while George focused on his writing. They spent weekends and holidays exploring (on a Vespa scooter), collecting numerous animals along the way.

Back in Switzerland, and reunited with David, they lived briefly in Oberengstringen to the west of Höngg. George divided his time between typing up natural history accounts and caring for a kitchen full of exotic animals – snakes, lizards, mice and geckos – he had brought back from Morocco.

Barbara and George separated in 1956. Barbara took full custody of David and emigrated to Australia to join a friend, Don Cameron, whom she and George had first met in Tangier. Barbara and Don married the day after their arrival in Australia and David was soon to have four younger half-sisters.

Meanwhile, George moved back to New York, where he found work as a longshoreman in Manhattan, while also doing some freelance writing. In his thirties, he married again and had a son, Jeremy. Soon afterwards, George survived bone cancer, despite having to have a leg amputated, but the marriage fell apart. George was forced to take early retirement, the only silver lining being that he received a lifelong union pension and had more time to write.

In about 1969, Ballou fell in love with Pamela Joyce, a telephone receptionist. Their daughter, Daniella, born in 1974, studied at Cornell University (as her paternal grandparents had done) and has subsequently held several senior positions related to global development, especially in regard to health initiatives and policy, an echo of her grandfather’s work with the W.H.O. and the Pan American Health Organization. The family lived for several years in the socially-diverse Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, close to Greenwich Village, and Daniella recalls that her father also earned some income from door-to-door Encyclopedia Britannica sales. During a family trip to Mexico, in about 1982, they traveled to Mexico City by bus and explored the area for a month staying in inexpensive hotels and hostels or with friends.

George Ballou, author of a 500-page work on Ajijic, died in May 1986. Is his book lost for ever, or will some intrepid researcher or garage-sale bargain hunter eventually unearth the long-lost manuscript? {see UPDATE at start of this post}

Acknowledgments:

- Sincere thanks to George Ballou’s elder son, David Cameron, and daughter, Daniella Ballou-Aares, for their help in compiling this profile, which is an updated version of a post first published 8 June 2015.

Sources:

- Amarillo Daily News, Amarillo, Texas, 25 Feb 1949

- David Cameron. 2015. “Anna Barbara Morgenthaler – Barbara Cameron – a biographical sketch.” (Unpublished)

- Time magazine, 5 Feb 1940

- University of New Mexico at Albuquerque. 1950. Yearbook of University of New Mexico at Albuquerque.

- New Mexico Lobo (published by the University of New Mexico), 28 July 1950.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

After the couple separated in about 1940, the children were sent out of London to live with their grandmother. When the war ended in 1945, they returned to live with their mother in London, where she was then working as a doctor.

After the couple separated in about 1940, the children were sent out of London to live with their grandmother. When the war ended in 1945, they returned to live with their mother in London, where she was then working as a doctor.