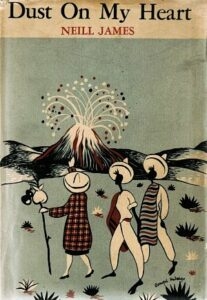

Neill James’ book Dust on my Heart is many visitors’ first introduction to the extensive English-language literature related to Lake Chapala. In the book, the self-styled “Petticoat Vagabond” tells of her adventures in Mexico and of two terrible accidents she suffered, the first on Popocatepetl Volcano and the second at Paricutín Volcano.

Cover of Dust on my Heart (1946) (Painting by Alejandro Rangel Hidalgo)

After two lengthy stays in hospital, James’ recuperation eventually brought her, in 1943, to the small village of Ajijic, which would be her home for the remainder of her long life. The final two chapters of Dust on my Heart describe her first impressions of Ajijic and of how she learned to appreciate the idiosyncrasies of pueblo life.

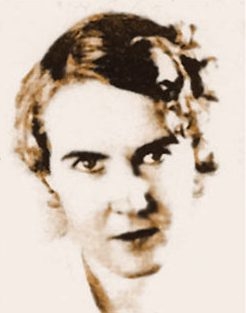

As with several other noteworthy Lake Chapala residents, separating fact from fiction in trying to sort out James’ story is tricky, and made more complex by hagiographic portrayals that simply repeat identical misinformation with no attempt to check sources or provide independent corroboration for claims made.

For example, we are led to believe that James was born on a cotton plantation in Grenada, Mississippi; was a woman of means who graduated from the University of Chicago; met Amelia Earhart; was visited in Ajijic by D. H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway and George Bernard Shaw; and pioneered the looms industry in Ajijic, before founding the Lake Chapala Society.

Unfortunately, not a single one of these claims is true. James was born in Gore Springs, Mississippi. While Gore Springs is near Grenada, James was not born on any plantation and her family was far from wealthy. She never attended the University of Chicago and almost certainly never met Amelia Earhart. The claims about Lawrence, Hemingway and Shaw are especially ludicrous. D. H. Lawrence was long dead by the time James first visited Mexico. Neither Hemingway (whom James may conceivably have met in 1941 in Hong Kong) nor Shaw ever visited Ajijic. James did not pioneer the looms industry in Ajijic and was never a member of the Lake Chapala Society prior to being accorded Honorary Membership a few years before she died!

In 1918, after studying stenography at the Industrial Institute and College for the Education of White Girls (later Mississippi State College for Women), James became a secretary at the War Department in Washington, D.C. Over the next decade, she traveled widely: from Hawaii to Japan, China, Korea, India, Germany, France, Costa Rica and New Zealand. In 1931, she settled on Hawaii to work at the Institute of Pacific Relations. Three years later, she left to travel again in Asia, returning to the U.S. via the Trans-Siberian railroad and Europe.

She then began travel writing and joined the stable of writers managed by Maxwell Perkins (who edited Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Erskine Caldwell, among others) at leading New York publishers Charles Scribner’s Sons. Prior to visiting Mexico, James had published three travel books: Petticoat Vagabond: Up and Down the World, (1937); Petticoat Vagabond: Among the Nomads (1939) and Petticoat Vagabond in Ainu Land: Up and Down Eastern Asia (1942).

Her early travels in Mexico in 1942, including a few weeks spent with the indigenous Otomi people, are entertainingly told, in rich, keenly-observed detail, in Dust on my Heart. During her first few months, James traveled to many very different parts of the country, from the capital city to impoverished rural mountain villages, from Acapulco to Chiapas.

It was only after two serious accidents, the first on Popocatepetl Volcano, the 17,899-foot peak near Mexico City, and the second on the slopes of the brand-new Paricutin Volcano in Michoacán, both recounted in gory detail in her book, and both requiring months in a Mexico City hospital, that James decided to recuperate at Lake Chapala.

It was early September 1943 when James first arrived at Ajijic. She eventually built her own house there. In order to complete the manuscript of her next Petticoat Vagabond book, James penned a couple of chapters about the village. This was the last book she ever wrote. As suddenly as she had started writing travel books, she stopped.

James had no independent wealth and needed to generate some income for herself. She began to buy plain white cotton blouses and pay local women piecemeal rates to embroider them. Many of the designs were created by American artist Sylvia Fein who was living in Ajijic at the time.

From the late 1940s on, James started three new tourist-related ventures – renting and flipping village homes; clothing (including weaving and silk production); and running her own tourist store – all of which remained active until well into the 1970s. Over the years, she also tried all manner of other potentially lucrative but ultimately short-lived ventures, ranging from keeping bees and selling honey to looking for buried treasure.

The short-term promise of her “revival” of embroidered blouses had fizzled out when marketing problems reduced its appeal. Meantime, Helen Goodridge, with her husband, Mort Carl, had started a commercial looms business in 1950 which was attracting attention. While James could not compete directly with their venture, she could, and did, begin to teach local women how to use smaller hand looms to weave small cotton and wool items such as women’s blouses and scarves. Whereas Goodridge employed mainly men as weavers (very much the tradition in this part of Mexico), James’s workforce was entirely female, in line with indigenous practice in southern Mexico.

Neill James’ store label

James also started a silk industry in Ajijic. She brought in hundreds of white mulberry trees, from Uruapan in Michoacán, and planted as many as she could in her own garden, offering others to families around the village. James also bought silkworm eggs and before long, Ajijic had a thriving silk production industry. James employed local women to weave the delicate silk thread into fine silk cloth. James began her silk industry in Ajijic in 1951, and it was in full flow by the early 1960s.

The third strand of her business activity was to open a small store out of her own home, selling items made in Ajijic as well as handicrafts from elsewhere. The store closed in 1974, when James announced her retirement.

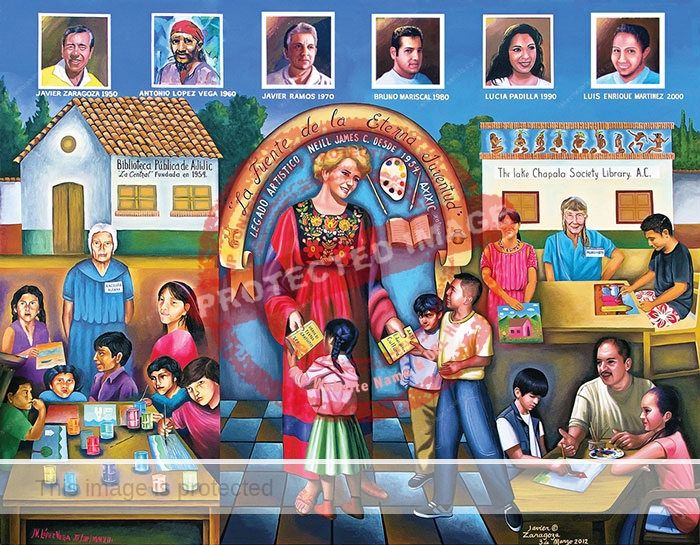

James is best remembered today for her many positive contributions to the health and education of her adopted community.

Having helped educate the children of her domestic helpers from the very beginning, James broadened her scope in about 1954 to open the area’s first public library (biblioteca pública), principally aimed at serving the needs of the local children.

The first library in Ajijic was a room, donated for the purpose, on Ocampo near Serna’s grocery store. James persuaded the municipio to part with funds for books and arranged for Angelita Aldana Padilla to oversee its activities. As their reward for reading and studying, students were offered the incentive of free art supplies and classes. This humble beginning led, after many twists and turns, to the justly-praised Children’s Art Program, now run by the Lake Chapala Society, that has helped nurture the talents of so many fine local artists.

At some point, a second library was opened, with its own supervisor, in a building James owned near Seis Esquinas, to help children living in the west end of the village. After the supervisor left, the running of La Colmena (The Beehive), as it was known, was turned over to some well-meaning teenagers. When the library was badly vandalized, the remaining books and supplies were moved to the original library, which James later moved to a building on her own property at Quinta Tzintzuntzan.

In 1977, James donated a property at Seis Esquinas (Ocampo #90) to be used as the village’s first Health Center (Centro de Salud).

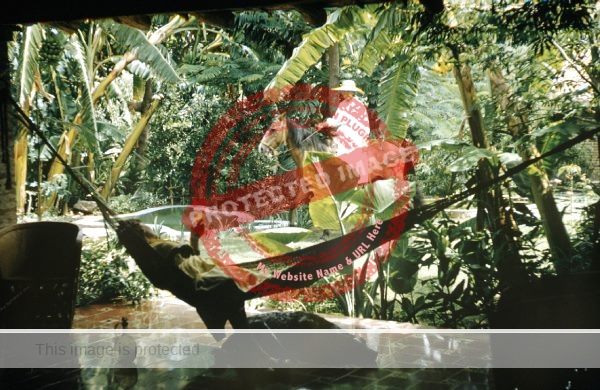

Neill James (hammock) and Zara (on horseback) in the gardens of Quinta Tzintzuntzan. Photo by Leonard McCombe for Life, 1957.

After her retirement in 1974, the wonderful gardens of Quinta Tzintzuntzan were no longer normally open to the public. However, in 1977, James agreed that the grounds could be open every Sunday afternoon as an art garden (jardín del arte) for a new artists’ group, the Young Painters of Ajijic (Jovenes Pintores de Ajijic).

In 1983, James offered to let the Lake Chapala Society use part of her Quinta Tzintzuntzan property rent-free for five years, provided it took over running the Ajijic children’s library located there. The Lake Chapala Society subsequently (1990) acquired legal title to the property in exchange for looking after Neill James in her final years. James died on Saturday 8 October 1994, only three months shy of her 100th birthday. Her ashes were interred at the base of a favorite tree in her beloved garden.

Given her early career as a travel writer, it is only fitting that the Mississippi University for Women (“The W”) now awards at least five Neill James Memorial Scholarships each year (worth up to $4000 each) to Creative Writing students. First offered in 2007, these scholarships are funded with the proceeds from a charitable trust established by her sister Jane.

It was James’ generosity that enabled the Lake Chapala Society to move from Chapala to Ajijic at a time when it was struggling and desperately needed new premises. Given her amazing accomplishments and legacy she left Lake Chapala, there is no possible need to embellish the story of Neill James, one of Lakeside’s most truly colorful, memorable and enterprising characters of all time.

Notes

James was not the creator of the saying, “When once the dust of Mexico has settled upon your heart, you cannot then find peace in any other land.” What she actually wrote (on the first page of Dust on My Heart) was “There is a saying, “When once the dust of Mexico has settled upon your heart, you cannot then find peace in any other land.”” James was merely quoting an old saying; it was not her creation. For more about the phrase’s use, past and present, see “Neill James, Anita Brenner and the origin of the popular Mexican saying about “Dust on my Heart.””

A much more detailed account of Neill James’ life can be found in chapters 13, 14, 21, 26, 34, and 39 of my Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village (2022).

And an even more detailed account is given in my research paper about James.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to Stephen Preston Banks, author of Kokio: A Novel Based on the Life of Neill James, and to Michael Eager and Judy King for sharing with me their insights into Neill James’ life and contributions to Ajijic.

Sources

- Anon. 1945. “Neill James in Mexico.” Modern Mexico (New York: Mexican Chamber of Commerce of the United States), Vol. 18 #5 (October 1945), 23, 28.

- Stephen Preston Banks. 2016. Kokio: A Novel Based on the Life of Neill James. Valley, Washington: Tellectual Press.

- Guadalajara Reporter, 17 September 1983, 18.

- Neill James. 1945. “I Live in Ajijic.” Modern Mexico (New York: Mexican Chamber of Commerce of the United States), Vol. 18 #5 (October 1945), 23-28. [Reprinted in El Ojo de Lago. Vol 17, #7 (March 1999].

- Neill James. 1946. Dust on My Heart. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Leonard McCombe (photos). “Yanks Who Don’t Go Home. Expatriates Settle Down to Live and Loaf in Mexico.” Life Magazine, 23 December 1957, 159-164.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

Johnny Bogan is set in a small town and is a character study and love story rolled into one. The striking cover art by Puerto Rican artist

Johnny Bogan is set in a small town and is a character study and love story rolled into one. The striking cover art by Puerto Rican artist

![Louis Stettner. Lake Chapala (1956). [postcard image on Delcampe website]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/stettner-louis-1956-chapala-s.jpg)

Later, when Jan was studying at the University of Texas at El Paso, she met and married artist Wesley Penn. Penn had friends who lived at Lake Chapala and suggested that they live in Mexico. Jan quickly agreed when she learned that Mexico wanted more English teachers ahead of hosting the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Later, when Jan was studying at the University of Texas at El Paso, she met and married artist Wesley Penn. Penn had friends who lived at Lake Chapala and suggested that they live in Mexico. Jan quickly agreed when she learned that Mexico wanted more English teachers ahead of hosting the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Richard Wendell Phillips Jr., the son of a New York stage actor, Wendell K. Phillips (1907-1991), and his first wife, Odielein Pearce, was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1929 and died on 2 October 2010. After graduating from Staunton Military Academy in Virginia in 1948, he planned to enter the U. S. Military academy at West Point. He later became an actor and played an uncredited part as a patient in Lilith (1964), written and directed by Robert Rossen.

Richard Wendell Phillips Jr., the son of a New York stage actor, Wendell K. Phillips (1907-1991), and his first wife, Odielein Pearce, was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1929 and died on 2 October 2010. After graduating from Staunton Military Academy in Virginia in 1948, he planned to enter the U. S. Military academy at West Point. He later became an actor and played an uncredited part as a patient in Lilith (1964), written and directed by Robert Rossen.

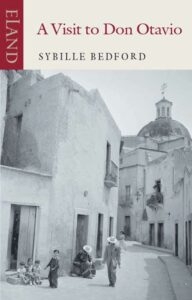

The Sudden View was first published in 1953 and later re-issued as A Visit to Don Otavio, the title by which it is now generally known. The book was based on a trip to Mexico in 1946-47. The book opens in New York as the author and her traveling companion, Esther Murphy Arthur (“E” in the book), start their train journey south. After exploring Mexico City and its environs, they then traveled to Guadalajara via Lake Pátzcuaro and Morelia. The remainder of the book is set almost entirely at Lake Chapala, with several relatively short and adventurous forays to other parts of the country.

The Sudden View was first published in 1953 and later re-issued as A Visit to Don Otavio, the title by which it is now generally known. The book was based on a trip to Mexico in 1946-47. The book opens in New York as the author and her traveling companion, Esther Murphy Arthur (“E” in the book), start their train journey south. After exploring Mexico City and its environs, they then traveled to Guadalajara via Lake Pátzcuaro and Morelia. The remainder of the book is set almost entirely at Lake Chapala, with several relatively short and adventurous forays to other parts of the country.

![Poster for inaugural event [Handwritten year should be 1977]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Pintores-Jovenes-Ajijic-Poster-Nueva-Posada-Womens-Loo-From-A-L-V.jpg)

Harry Alverson Franck (1881-1962) was one of the foremost travel writers of the first half of the twentieth century, often taking temporary employment to help finance the next stage of his trip. Franck was a prolific writer, turning out some thirty travel books in a very productive life, including volumes on Mexico, Spain, Andes, Germany, Patagonia, the West Indies, China, Japan, Siam (Thailand), the Moslem World, Greece, Scandinavia, British Isles, Soviet Union, Hawaii and Alaska.

Harry Alverson Franck (1881-1962) was one of the foremost travel writers of the first half of the twentieth century, often taking temporary employment to help finance the next stage of his trip. Franck was a prolific writer, turning out some thirty travel books in a very productive life, including volumes on Mexico, Spain, Andes, Germany, Patagonia, the West Indies, China, Japan, Siam (Thailand), the Moslem World, Greece, Scandinavia, British Isles, Soviet Union, Hawaii and Alaska.

These names were a useful starting point for me when I began researching the artists and authors associated with Lake Chapala. Over the past decade, I have looked into the lives and works of all of the artists named by James and have now published short profiles of all but one of them.

These names were a useful starting point for me when I began researching the artists and authors associated with Lake Chapala. Over the past decade, I have looked into the lives and works of all of the artists named by James and have now published short profiles of all but one of them.