By the 1970s the Ajijic retirement community was sufficiently established that it attracted academic attention. The earliest study, never formally published, was by Dr Edwin G Flittie, a professor of sociology at the University of Wyoming. Flittie visited in 1973 and subsequently presented copies of “Retirement in the Sun,” his analysis of the retirement community, to the Lake Chapala Society Library. Like several later studies of foreign migrants, Flittie considered the Chapala-Ajijic region as a single unit, and not as two communities with their distinct histories as regards tourism and retirement. Flittie interviewed more than 100 retirees and found that many had failed to appreciate the substantial cultural differences between the US and Mexico, or recognized that the emphasis for many local residents was “not on material gain but rather on the attainment of a satisfying existence traditionally based upon agrarian economic self-sufficiency.”

Flittie estimated that about 60% of retirees were aged 60 to 74, and 14% were 75 or older. Very few were fluent in Spanish and 88% reported that their social life centered on fellow expatriates and other English-speaking individuals. Flittie found that most retirees lived much as they would have lived in the US. The main problems they faced were related to excessive drinking, marital and family discord (men adapted better than women), boredom, bribery, interactions with the local community, domestic help and old age. Flittie returned briefly in December 1977 to research the impacts of the massive 1976 devaluation of the peso from 12.5 pesos to a dollar to about 22.5 pesos to a dollar.

Juan José Medeles Romero, in his 1975 thesis proposing an urban development plan for Ajijic, detailed how the village had approximately tripled in size between 1900 and 1950, and then doubled in size the following decade. And this was even before the addition of numerous subdivisions such as Rancho del Oro and La Floresta. Curiously, Medeles ignored the impacts of foreigners and only mentioned them in passing.

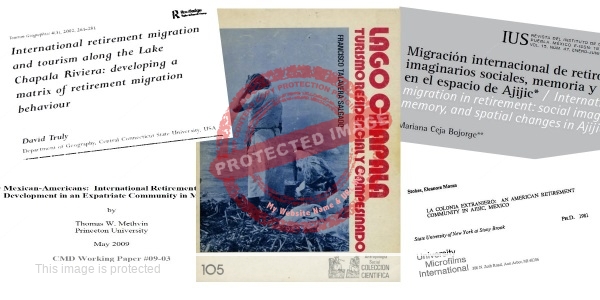

A few years later, Mexican sociologist Francisco Talavera Salgado focused solely on Ajijic when, in Lago Chapala, turismo residencial y campesinado, he examined the varied impacts of foreign residents on the local community. His important findings are described in detail in several chapters of Foreign Footprints.

At the end of the 1970s anthropologist Eleanore Moran Stokes also homed in on Ajijic. She divided the evolution of the village after ‘Discovery’ into three phases: Founder (1940s to mid 1950s), Expansionary (mid 1950s to mid 1970s) and Established Colony (mid 1970s through the 1980s).

Several of her informants considered the representation of Ajijic in the Dane Chandos novels (Founder phase) to be non-fiction; to Stokes, this was “the local equivalent to a creation myth.” The nature of migrants changed in each stage. During the Founder phase, Ajijic served, in her view, largely as an artists’ colony. These “young single well-traveled” artists were resourceful and independent individuals who had little impact on the village beyond the employment of domestic help; most of them learned the language, liked the cuisine, and blended into the local community.

Later (Expansionary phase) arrivals tended to be members of the affluent and retired middle class, many of whom had traveled widely, either in the military or working for international corporations. These newer arrivals did materially change the village. By infusing cash into the local economy and starting businesses they created “a new wage labor class in the village.” By upgrading village homes they distinguished their residences from those of local families. By retaining their language, food and lifestyle preferences, these incomers established a social distance from their host community, even forming “privileged associations for recreation, friendship and religion.” In essence, many of these migrants wanted to make many aspects of life in Ajijic more like the US.

Such tendencies continued into the Established Colony phase. Vacant houses became increasingly scarce and agricultural land was parceled for vacation and retirement homes. The foreign community greatly boosted philanthropic activities, especially those helping children, though this stage also saw a marked social stratification develop within the foreign community.

Stokes estimated that foreigners occupied about 300 of the 950 houses in the village in 1979, but comprised less than 8% of the population. Like Talavera, she viewed retirees as agents of change, not merely spectators of ongoing social processes, though they felt a sense of powerlessness in regards to what they saw as deficiencies in the provision of such services as water, electricity, telephone, garbage collection and police.

Sociologist Charlotte Wolf, who moved to Ajijic with husband Rene in the early 1990s, was interested in how individual retirees adapted and constructed a new life for themselves in Ajijic.

Among the conclusions in 1997 of Lorena Melton Young Otero, who looked specifically at US retirees, was that they created new jobs, donated to charities and hastened “modernization,” but that their presence was driving up the cost of living for local people. In a later paper, she examined in detail the mourning ritual and other customs in Ajijic following the death of a child (angelito).

The evolutionary framework developed by Stokes was used by geographer David Truly to examine how the type of migrant has changed over the years and to develop a matrix of retirement migration behavior. Like Stokes, Truly concluded in 2002 that newer visitors (including retirees), and unlike earlier migrants, had less desire to adapt to the local culture and were more keen on ‘importing a lifestyle’ to the area.

Stephen Banks, author of Kokio: A Novel Based on the Life of Neill James, conducted dozens of interviews to study the identity narratives of retirees while living in Ajijic in 2002-2003. All respondents depicted Mexicans, both generally and individually, as “happy, warm and friendly, polite and courteous, helpful and resourceful.” However, at the same time, many shared instances in which they thought Mexicans had been untrustworthy, inaccessible, lazy and incompetent. Banks concluded that the responses revealed:

a struggle to conserve cultural identities in the face of a resistant host culture that has been colonized…. The Lakeside economy is dominated by expatriate consumer demand; indigenous commerce in fishing has disappeared as new employment opportunities opened up in the services sector; local prices for real estate (routinely listed in US dollars), restaurant dining, hotel lodging and most consumer goods are higher than in comparable non-retirement areas; traditional Mexican community life centered around the family has been supplemented, and in some cases supplanted, by expatriate community life centered around public assistance and volunteer programs… and the uniform use of Spanish in public life is displaced by the use of English.”

Lucía González Terreros is the lead author of two recent papers that explore the complexity of defining residential tourism and how alternative definitions relate to property rights, transaction costs and common goods. The research arose from her personal concerns about the rapid increase in the number of foreigners in Ajijic since 1990.

Equally interesting is the work of Francisco Díaz Copado, who looked at how Ajijic is being shaped by both local and foreign “rituals,” such as the annual Fiesta of San Andrés and the Chili Cookoff respectively. In his 2013 report, Díaz Copado also examined “the different ways in which people describe and name the different zones of Ajijic… [which] reflect some historical conflicts.” Two annotated maps sharply contrast traditional locations and names with those used by retirees.

Marisa Raditsch investigated the impacts of international migrants settling in the municipality of Chapala “based on the perceptions of Mexican people in the receiving context.” This 2015 study found that these perceptions tended “to be favorable in terms of generating employment and contributing to the community; and unfavorable in terms of rising costs of living and some changes in local culture.”

Social anthropologist Vaira Avota, writing in 2016, also looked at the relations between foreigners and locals in Ajijic. She drew a sharp distinction between “traditional immigrants,” who wanted to truly understand Mexico’s culture, traditions,… [learn] Spanish and willingly participate in local activities,” and “new immigrants,” who wanted to live in a version of the US transplanted to Lake Chapala.

The impacts of this shift in migrant type were further explored by Mexican researcher Mariana Ceja Bojorge, who focused squarely on the relationships and interactions between local Ajijitecos and foreigners. She concluded in 2021 that the shift “endangers the acceptance of the presence of the other” and that “Although the presence of foreigners has generated economic well-being in the area, it has also been responsible for the reconfiguration of space, where locals have been forced to leave their territory.”

This is a lightly edited excerpt from the concluding chapter of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village, which offers a comprehensive history of Ajijic including full bibliographic details of all the studies mentioned.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

On their return to the US, Tomkins struggled to write a second novel, but did get several short stories published. To make ends meet, he became a journalist, working first for Radio Free Europe (1953-1957) and then Newsweek. He had a freelance contribution to the New Yorker accepted in 1958, and joined the magazine two years later as a staff writer. In addition to short stories and humor pieces, he branched out into nonfiction. Over two decades, he focused on chronicling the rapidly evolving New York City art scene. He was the New Yorker’s official art critic in the early 1980s, and responsible for hundreds of art reviews and profiles for the magazine’s “Art World” column.

On their return to the US, Tomkins struggled to write a second novel, but did get several short stories published. To make ends meet, he became a journalist, working first for Radio Free Europe (1953-1957) and then Newsweek. He had a freelance contribution to the New Yorker accepted in 1958, and joined the magazine two years later as a staff writer. In addition to short stories and humor pieces, he branched out into nonfiction. Over two decades, he focused on chronicling the rapidly evolving New York City art scene. He was the New Yorker’s official art critic in the early 1980s, and responsible for hundreds of art reviews and profiles for the magazine’s “Art World” column.

Sarah continued her art education with two years at the Colorado College of Fine Arts in Colorado Springs. Her fellow students included

Sarah continued her art education with two years at the Colorado College of Fine Arts in Colorado Springs. Her fellow students included