Acclaimed expressionist artist Abby Rubinstein (née Addis) and her second husband, Jules, also an accomplished artist, lived in Ajijic from 1966 to 1976.

Abby S Addis was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 6 August 1928.

In 1945, at age 15, Abby was accepted on a scholarship into the Brooklyn Museum Art School, where famous Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo was one of her tutors, alongside Joseph Presser, George Pippin, Frances Chris and John Bindrum.

Abby taught nursery school and married young. She had two children with her first husband, Arthur G. Kunkin, a colorful character who later (in Los Angeles) became the publisher of the hippie-oriented underground newspaper The Free Press. The couple had left New York in 1950 for Los Angeles, where Abby studied briefly with muralist Leonard Herbert at the Otis Art Institute and became director of Westwood Temple’s daily nursery.

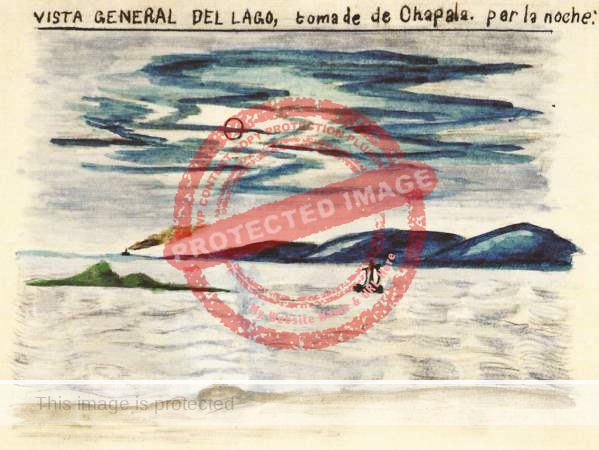

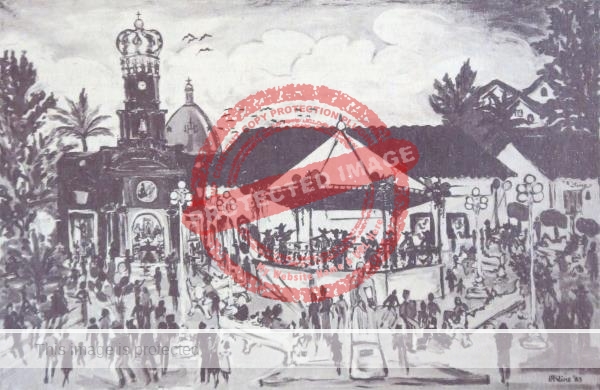

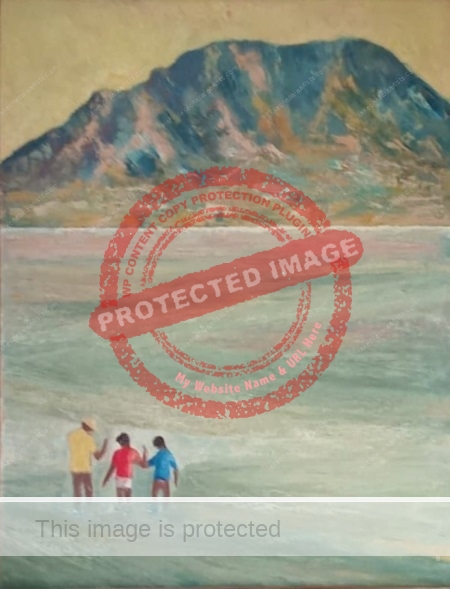

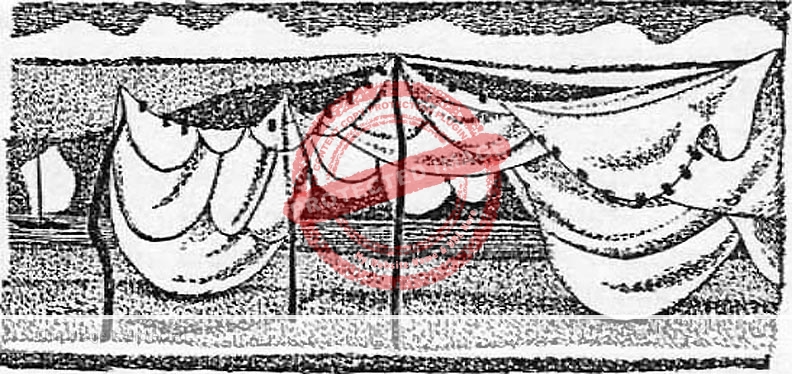

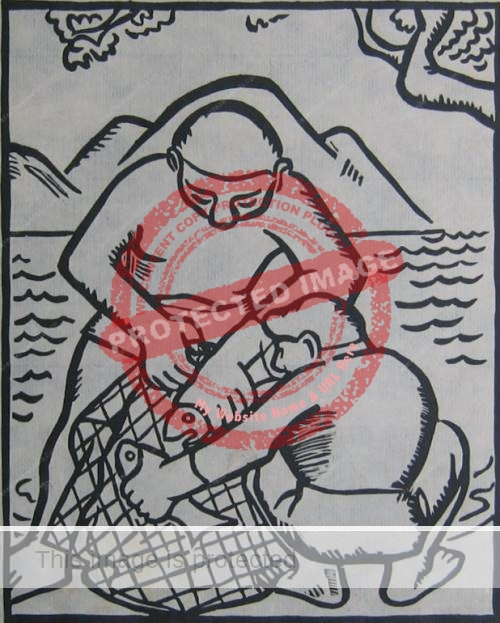

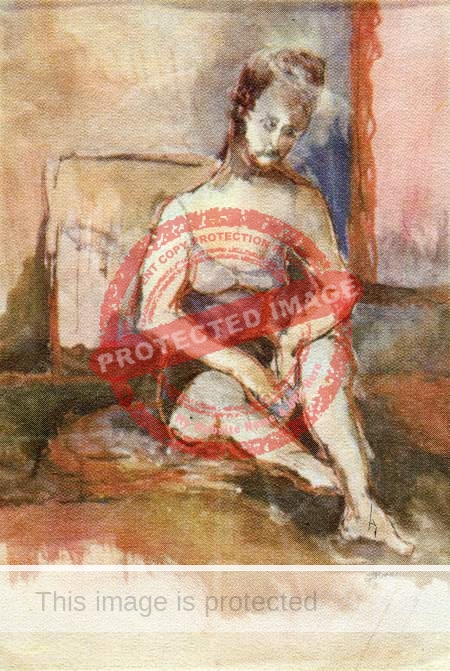

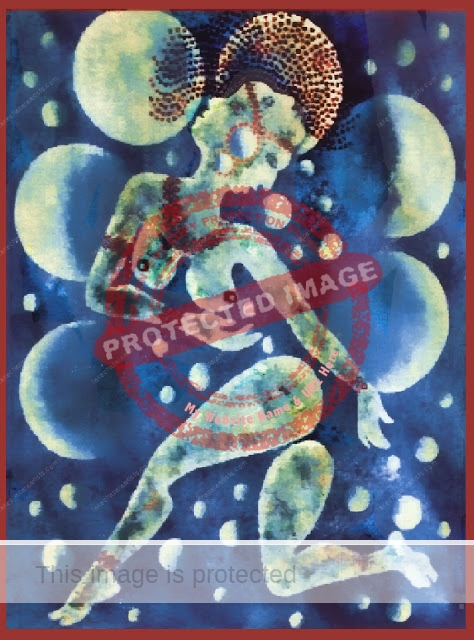

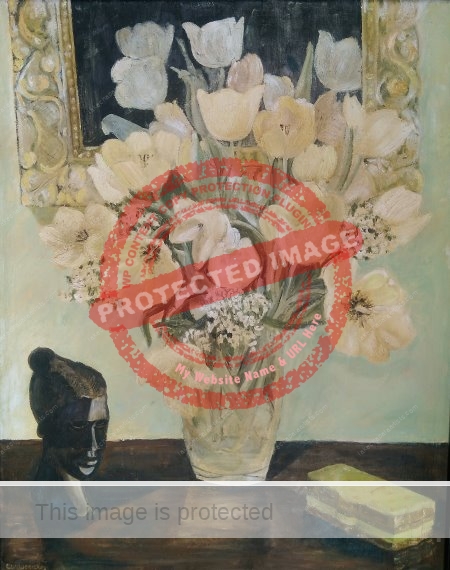

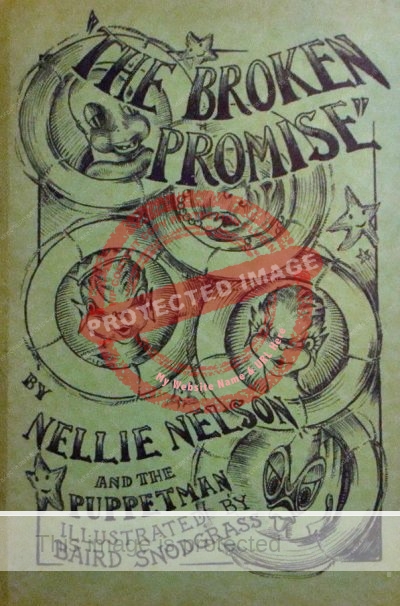

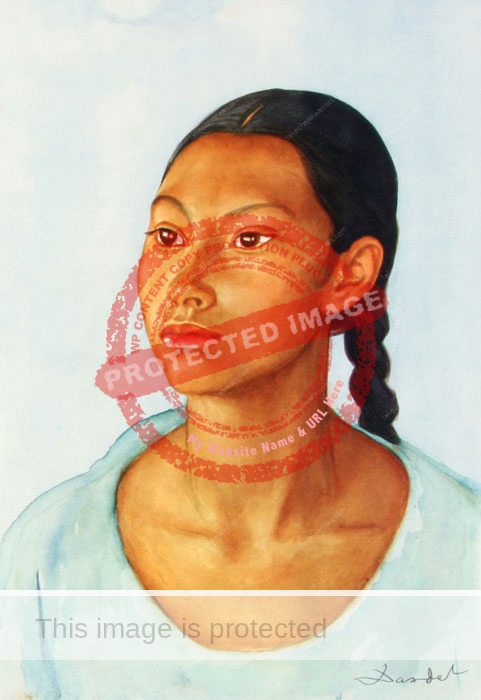

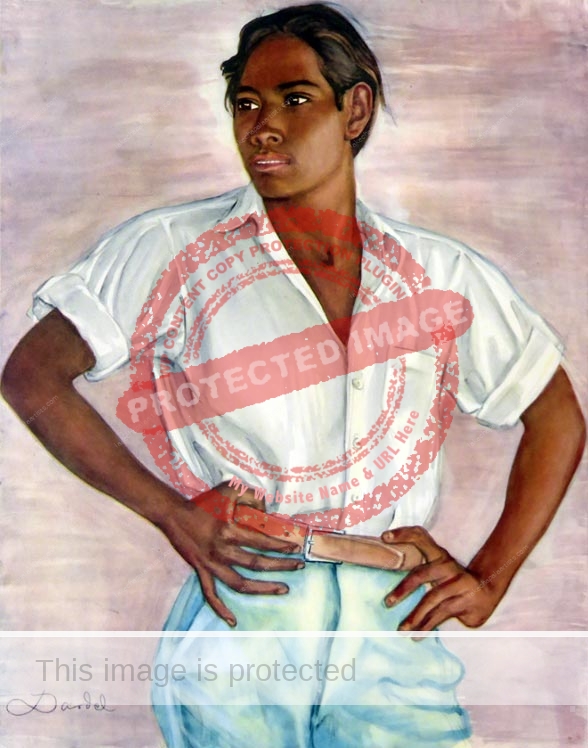

Abby Rubinstein. Untitled. Reproduced by kind permission of Ricardo Santana.

More than a decade later, and after the end of her first marriage, Abby married Jules Rubinstein in Los Angeles. Shortly after marrying, the newly-wed couple moved to Ajijic.

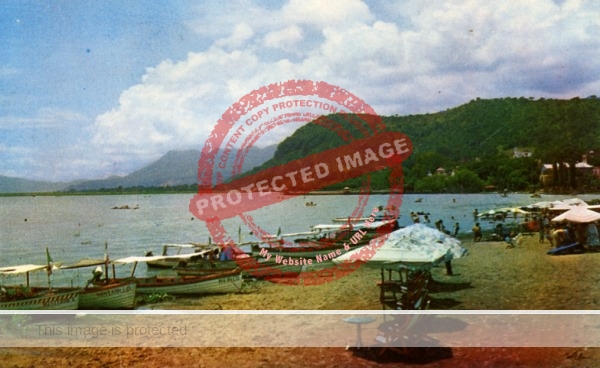

During their years in Ajijic, both Abby and Jules developed reputations as fine artists, attracting a steady stream of international visitors and art collectors to their home and studios.

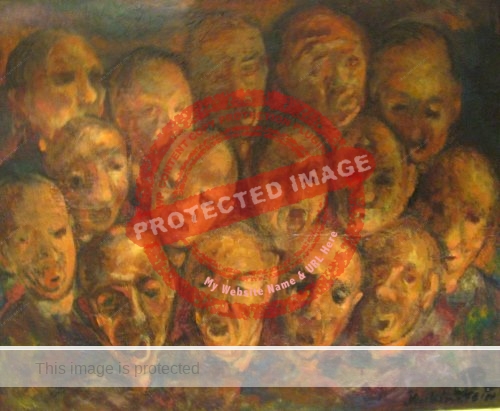

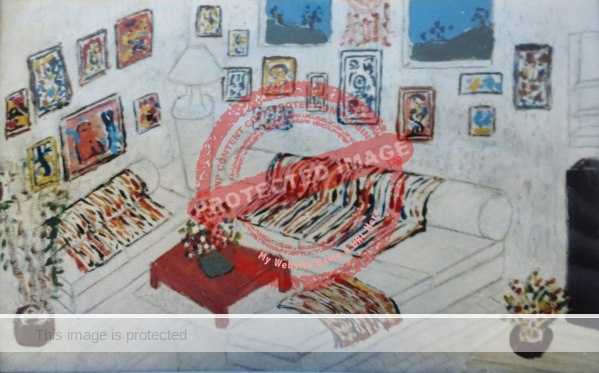

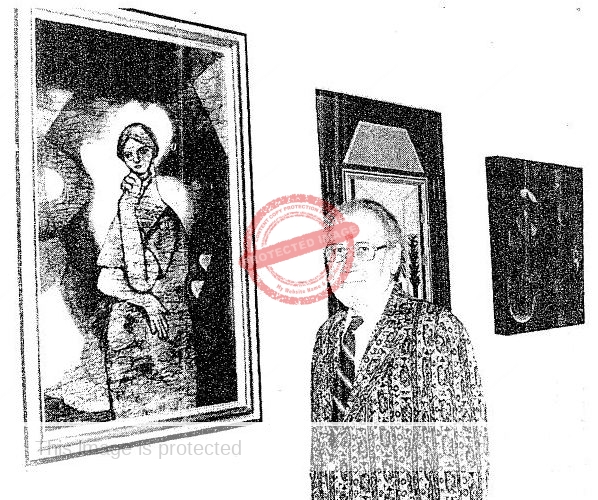

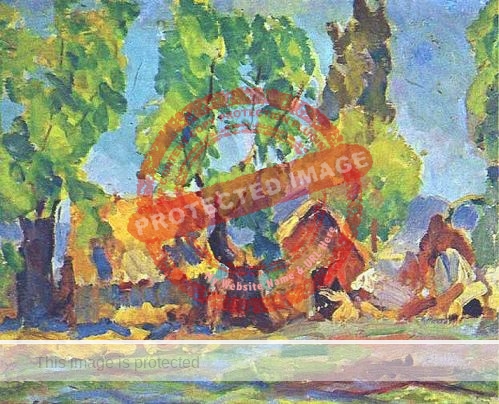

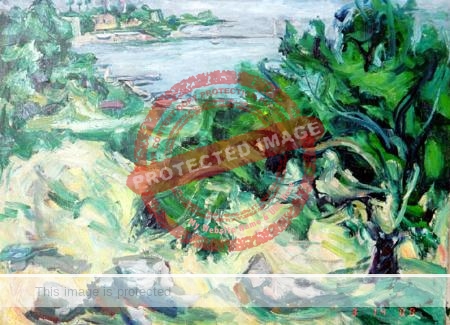

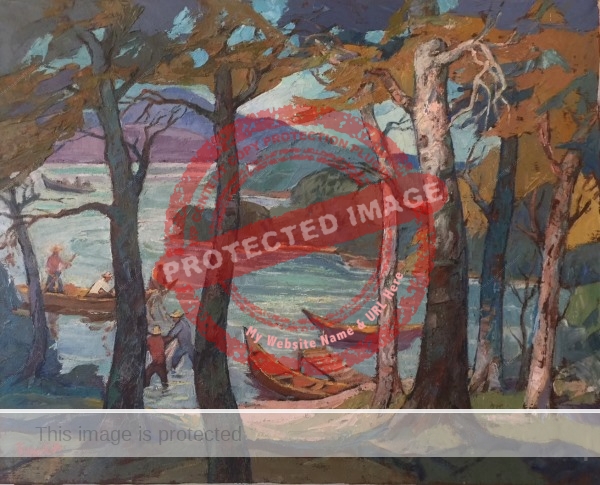

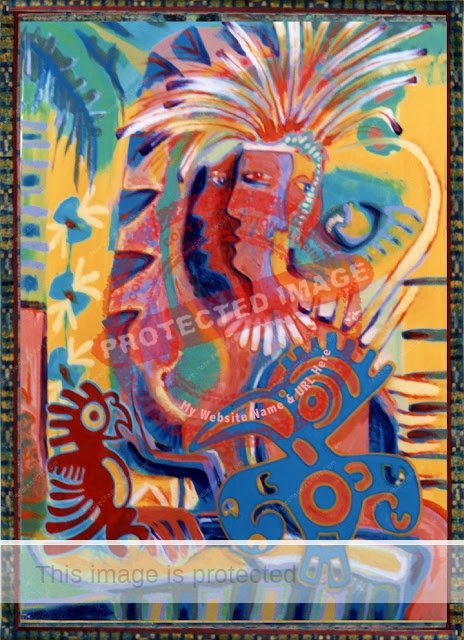

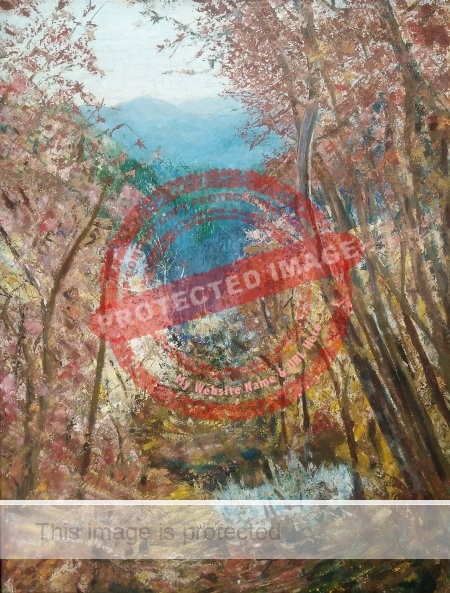

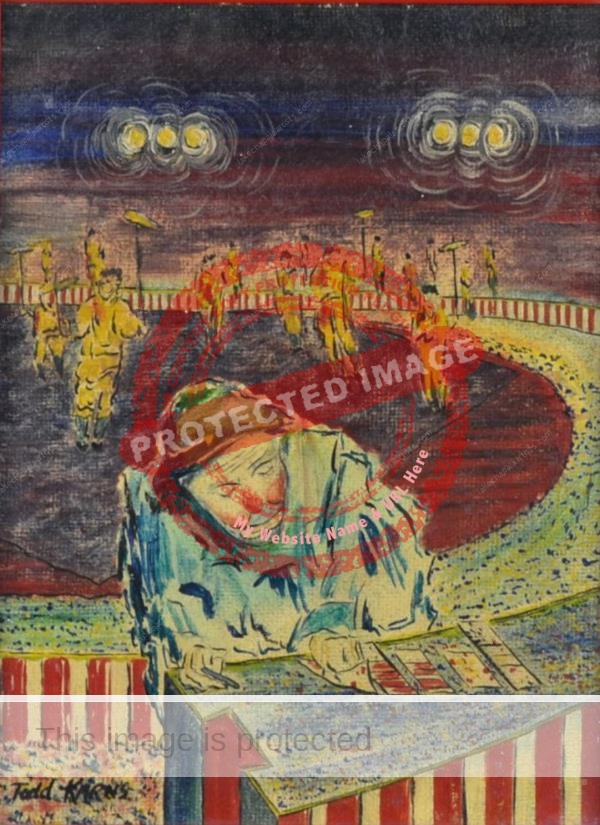

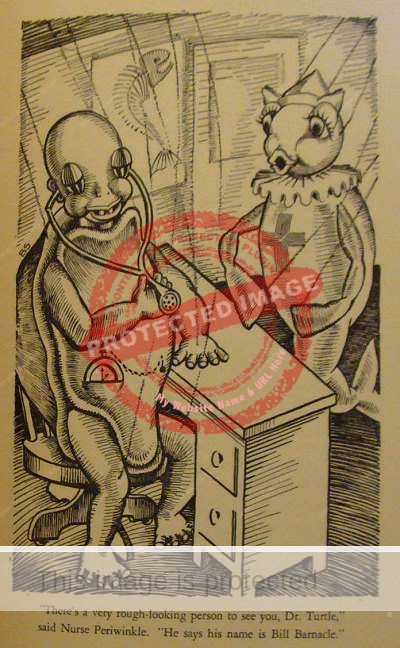

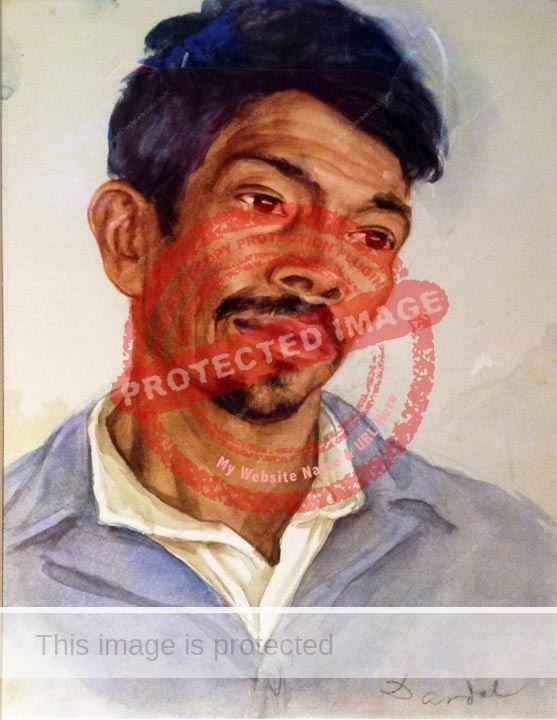

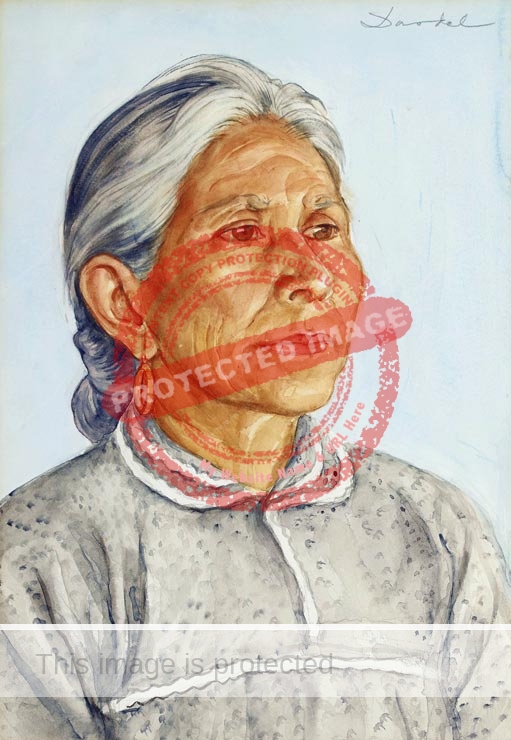

Abby Rubinstein. ca 1970. The Just Man. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist

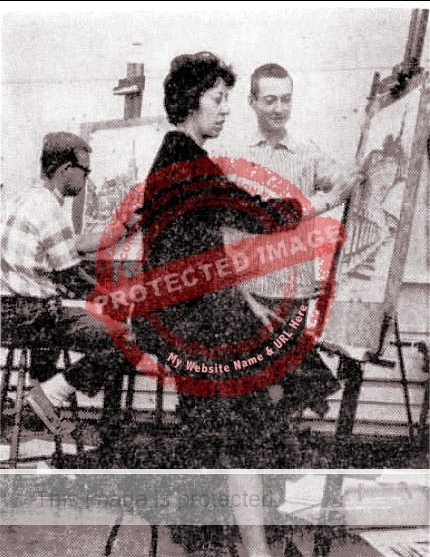

In 1967, not long after moving to Ajijic, some of Abby’s oil paintings were on show at an Open Studio of the “Harrington Collection” in Guadalajara.

During the Mexico City Olympics in 1968 the Rubinsteins served on the city of Guadalajara cultural team and held an inaugural joint exhibition of paintings at the Galeria Municipal (Chapultepec and España). The exhibit opened on 3 June 1968 and was sponsored by the Olympic Cultural Committee as part of their International Festival of the Arts. In nine days over 3000 people came to view this exhibition.

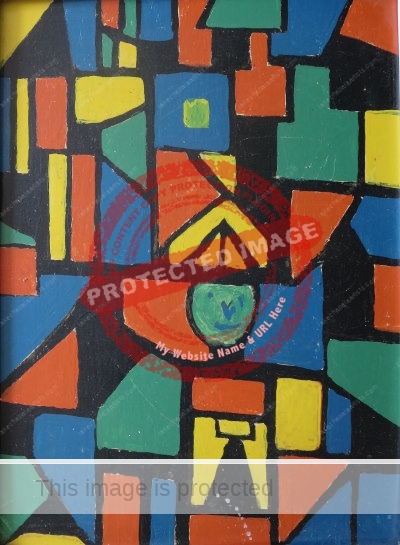

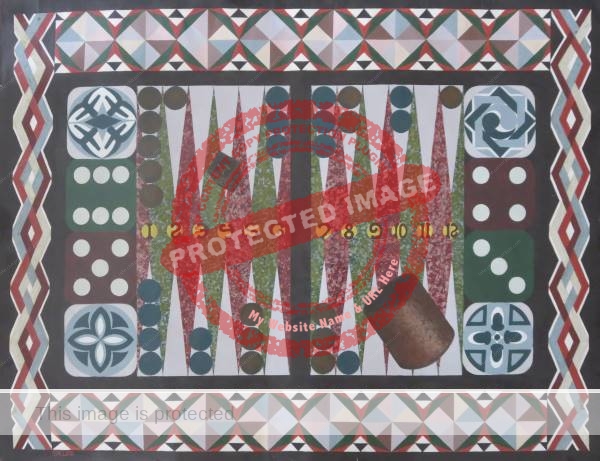

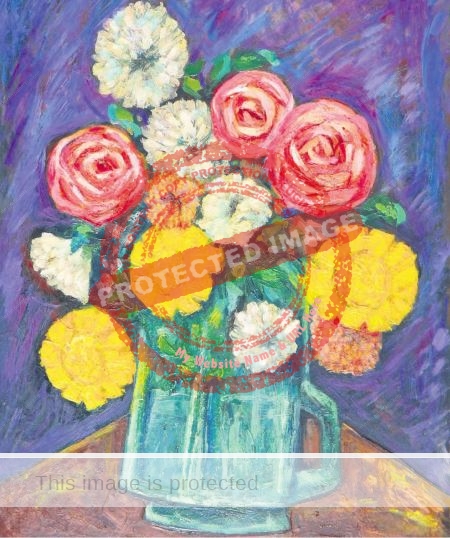

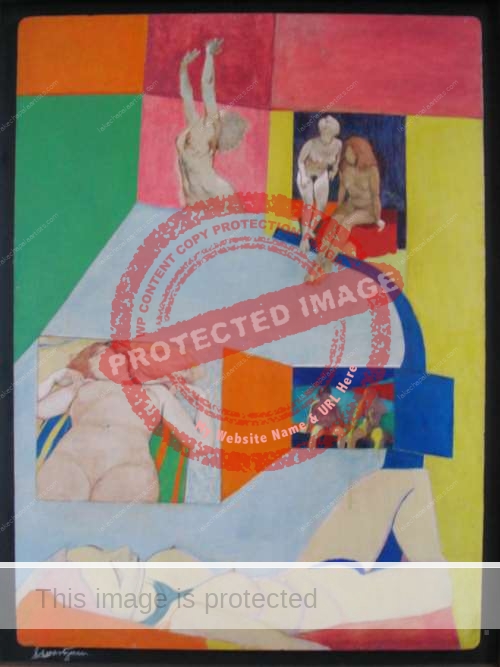

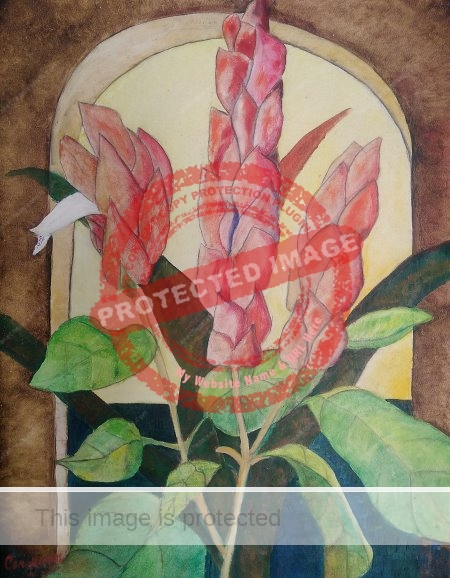

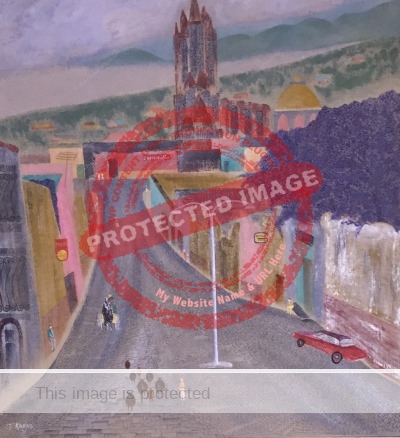

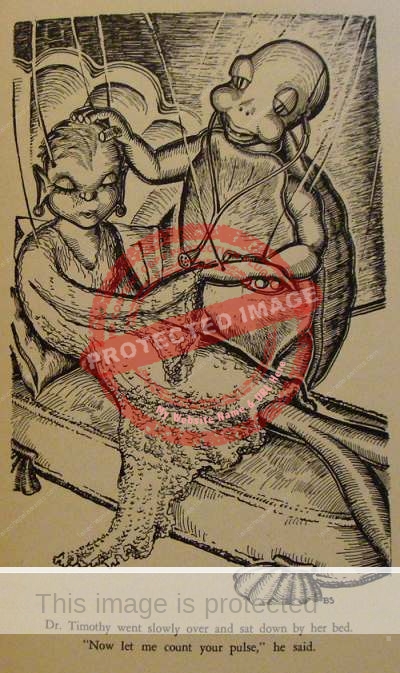

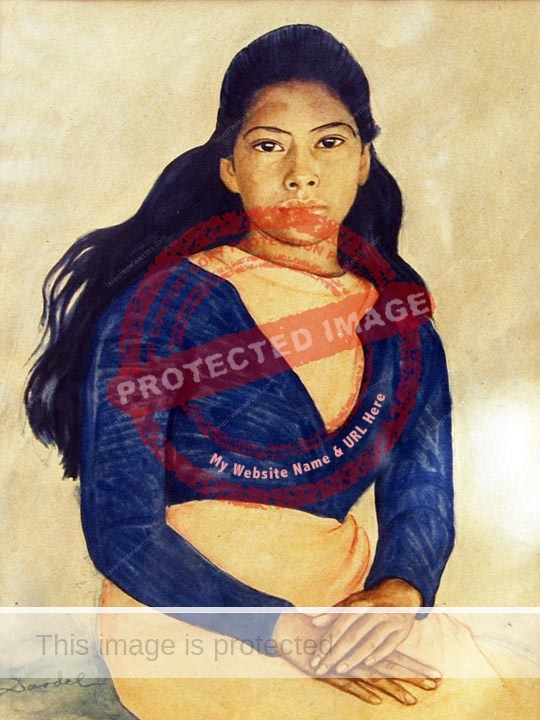

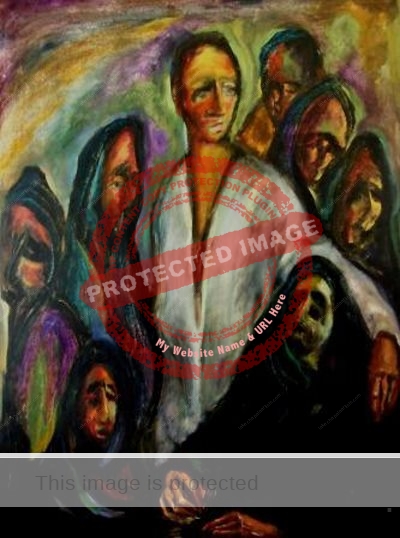

Abby Rubinstein. ca 1970. The Torah. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist

The following year, two of Abby’s oils were chosen for inclusion in the Semana Cultural Americana – American Artists’ Exhibit, which opened at the Instituto Cultural Mexicano Norteamericano de Jalisco, A.C. (Tolsa #300) in late June. The juried group show featured 94 pieces by 42 US artists from Guadalajara, the Lake area and San Miguel de Allende. The four-man jury was comprised of Francisco Rodriguez Caracalla, Director of Escuela de Artes Plásticas, and three art critics; José Luis Meza Inda, Fernando Larroca, and Victor Hugo Lomeli.

In 1972, the Rubinsteins held another joint exhibition, of about 15 paintings each, at the Instituto Cultural Mexicano Norteamericano de Jalisco (Mexican-North American Cultural Institute). A reviewer (probably Allyn Hunt) asserted in the Colony (Guadalajara) Reporter that, “Abby has made a quietly profound and eloquent statement about the world we live in and those that people it,” while Jules’ works are “expressionism… with a feeling of allegorical mysticism.”

According to her resume, Abby showed several oil paintings and drawings in an exhibit at the Escuela de Artesanias (Handicrafts School) in Ajijic in 1975. If anyone can supply more information about this show, and the names of other artists involved, please get in touch.

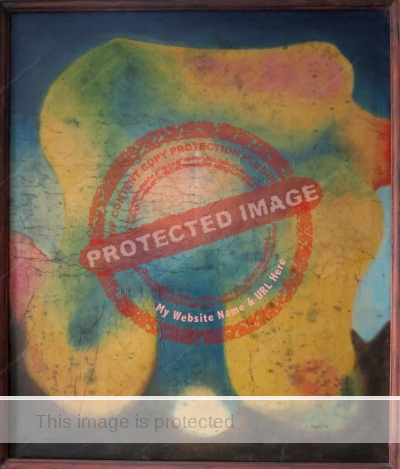

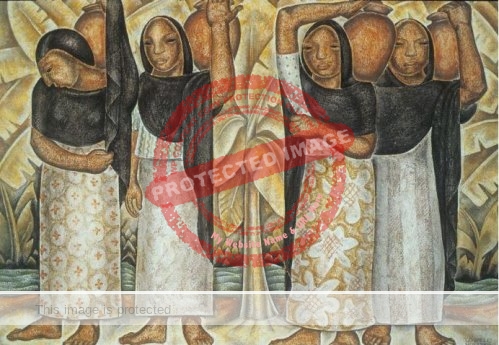

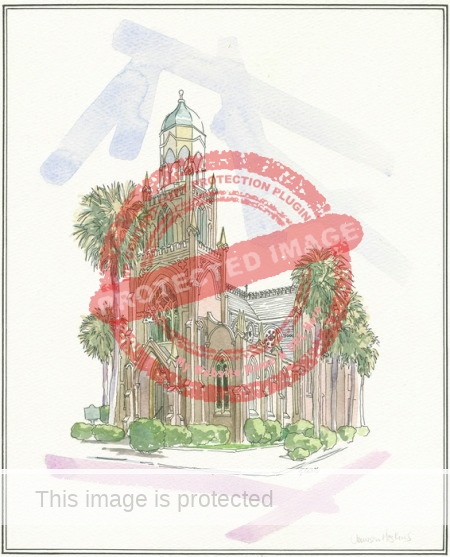

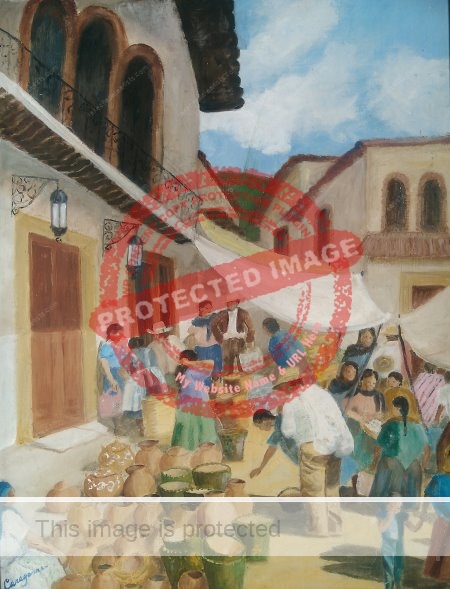

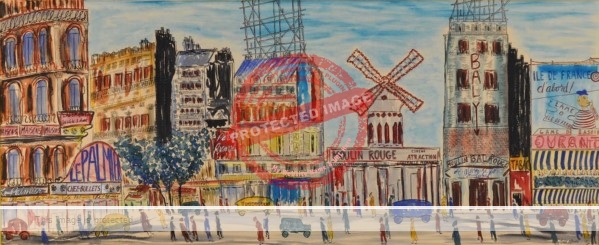

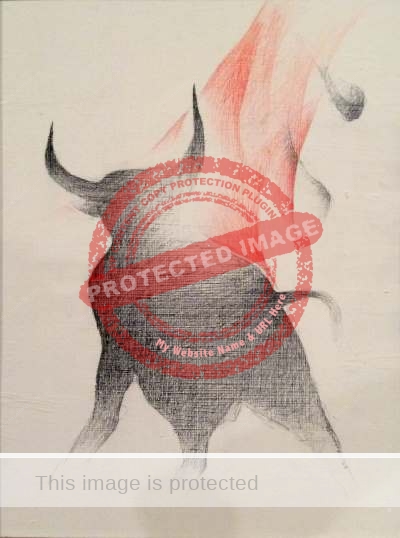

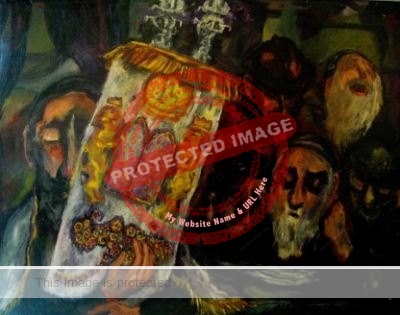

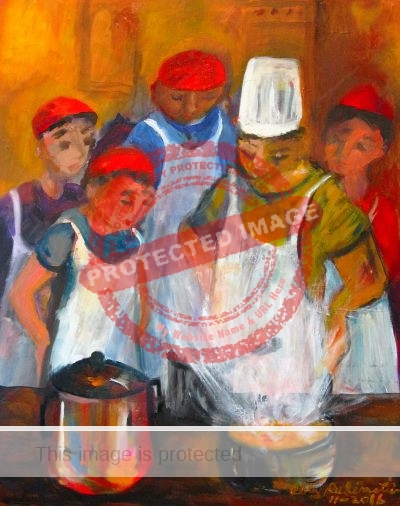

Abby Rubinstein. 2016. Chef’s School. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist

After they left Ajijic in 1976, the couple lived for a year in Israel, where Abby lectured on Expressionist art and its philosophy, before re-crossing the Atlantic to settle in Visalia, California.

Abby and her husband held a special exhibition at Riverside Municipal Museum in 1981. Entitled “Rubinstein and Rubinstein: Myth and Religion in American Expressionism,” the show featured 31 paintings from their personal collection.

Abby studied at the University of San Francisco and gained her bachelor’s degree in Public Administration and Art in 1983 and her Masters degree in Fine Arts two years later.

Her solo exhibitions, of oil paintings unless otherwise indicated, include: Brooklyn Museum, New York (drawings and watercolors, 1948); Mariana Von Allesh Gallery, Manhattan (1949); University of Guadalajara Gallery (1967); Misrachi Gallery, Mexico City (1969); Beth Giora, Jerusalem, Israel (1976); Visalia Convention Center, California (oils, watercolors and pastels, 1993); Lawrence Collins Fine Art Gallery, Visalia (2000); Adamo Gallery, Las Vegas (2002); Addi Gallery, Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii (2004); EaselHeads Gallery, Visalia (2004–2009).

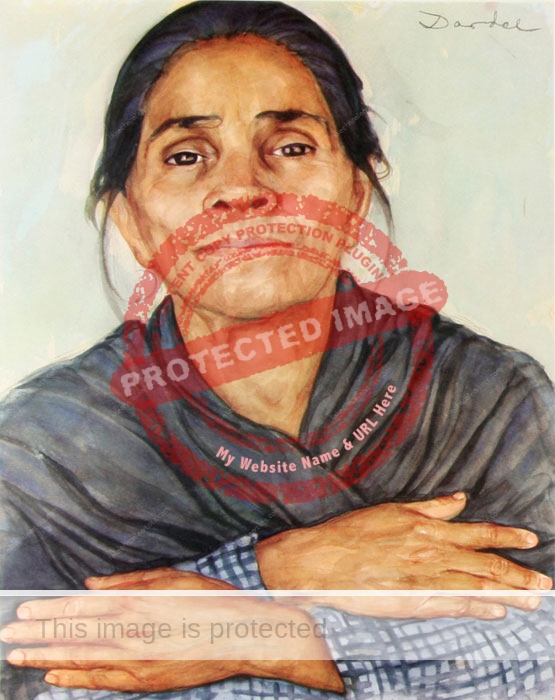

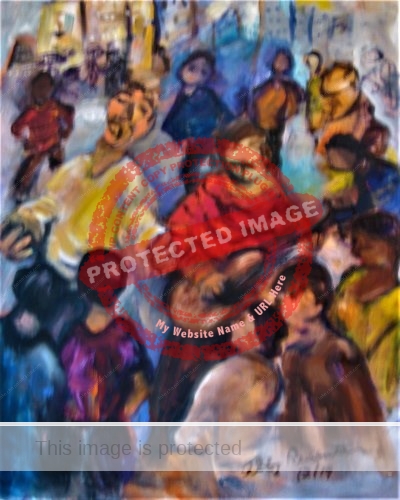

Abby Rubinstein. 2019. The Street Singer. Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

In addition to the various group shows in Mexico, Abby’s paintings and drawings have been chosen for shows in Santa Monica Library, California (1966); Swanson Food Co., Minneapolis (1974); Korenbrut Studio, Mexico City (1975); Temple Beth Israel, Fresno, California (1978) and Bowman Gallery, Visalia (1980).

A 2017 newspaper article labeled her work ‘humanist expressionism,’ explaining that when she started a painting, the artist began by looking for “movement, color or atmosphere that corresponds with my innermost emotions,” before “bending it and developing it until it speaks for me and meets others with whom it can have a conversation.”

The article quoted Abby’s belief that

a true work of art transcends time barriers and finds an indefinable element that touches a main spring of intuitive response within a viewer and affects a very intimate meeting. It’s that intimate meeting that I seek when I paint.”

Abby still lives in Visalia and continues to paint and exhibit. As she explained by email:

“I believe that a search for intimacy in my paintings is what distinguishes them as mine. Frequently, people refer to the color in my work, but I think that the colors that I use are only components in the construction of the idea. To begin with I seek the soul of the subject. Then without ever losing sight of this, I bring together my emotion and consciousness in the development of the painting until it satisfies me.”

As the great sculptor Saul Bazerman answered, when asked how he knew when he was finished with a piece, “When it is full and I am empty.”

Abby Rubinsteins’s paintings are in numerous private collections in several countries. Please visit her website for more details and many more images of her superb work.

Acknowledgment

- My thanks to Abby Rubinstein for her help via email in compiling this profile and to Katie Goodridge Ingram and Peter Huf for sharing with me their memories of Abby Rubinstein. Sincere thanks, too, to Ricardo Santana for showing me the untitled work by Abby Rubinstein in his private collection.

Sources

- Colony (Guadalajara) Reporter: 15 June 1968; 6 Feb 1971; 3 Apr 1971; 18 March 1972; CR 21 Feb 1976;

- Los Angeles Times: 26 Aug 1962, 282; 5 April 1967, 2; LAT 6 Dec 1968, 2; 29 Aug 1970, 6.

- San Bernardino County Sun, 19 June 1981, 48.

- The Sun-Gazette. March 22, 2017. “Renowned artist shows ‘humanist expressionism’ at Exeter gallery.”

- Edward J Sylvester. 1975. “So you’d like to retire in Mexico?” Tucson Daily Citizen, 13 Sep 1975, 9-11.

- Visalia Times-Delta: “Painter Abby Rubinstein reflects on her long career, art.”

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.