Among the more innovative artists experimenting in Ajijic during the 1950s is one almost-forgotten American painter: Don Martin.

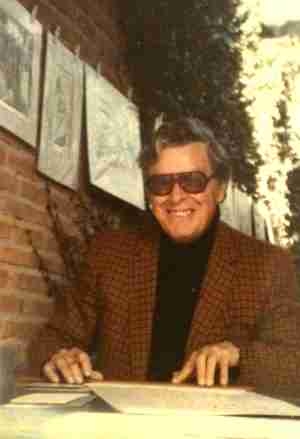

Don Martin in Mexico. Reproduced by kind permission of Joan Gilbert Martin.

Donald Theodore Martin (1931-1989) lived in Ajijic from early in 1954 until late summer, 1961. As Joan Gilbert Martin points out, on the website she established as a tribute to her late husband, his “long stay” in Ajijic proved to be “a most creative period.”

Donald Theodore Martin was born in Akron, Ohio, on 17 June 1931 and died on 6 November 1989.

Martin studied at the Art Student’s League in New York City (1948), where his teachers included German-born abstract painter Carl Holty and Sidney Laufman, and at the Akron Art institute in Ohio (1949) with Leroy Flint. He also took classes in New Orleans, in 1953, with Charles Campbell.

It was during his time in New Orleans, that Martin met artist and folk singer Lori Fair, Beat poet and photographer Anne McKeever, and artist and jazz musician George Abend. McKeever left New Orleans to take up an English-teaching job in Guadalajara in 1953, and was instrumental in arranging several exhibits of Don Martin’s work shortly after he arrived the following year.

Martin moved from New Orleans early in 1954 to live with Lori Fair in Ajijic in a house she bought on Calle Nicolas Bravo/Galeana. He remained in the house even after the couple separated in about 1958, at which point Lori moved to Mexico City. Lori subsequently married and changed her name to Bhavani Escalante. Now well into her nineties, she lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Moving to Mexico brought Martin the self-confidence to experiment and explore different media. In the words of Joan Gilbert Martin, his widow,

“On arriving at the Mexican border, he told the authorities he was an artist and, to his surprise and delight, was treated with honor; in the states he would be told to get a job. He fell in love with the people, the animals (the bulls, the roosters, the stray dogs), the lake, and the mountains. And he found a home as an artist. His work was appreciated in the village, it was a productive time.”

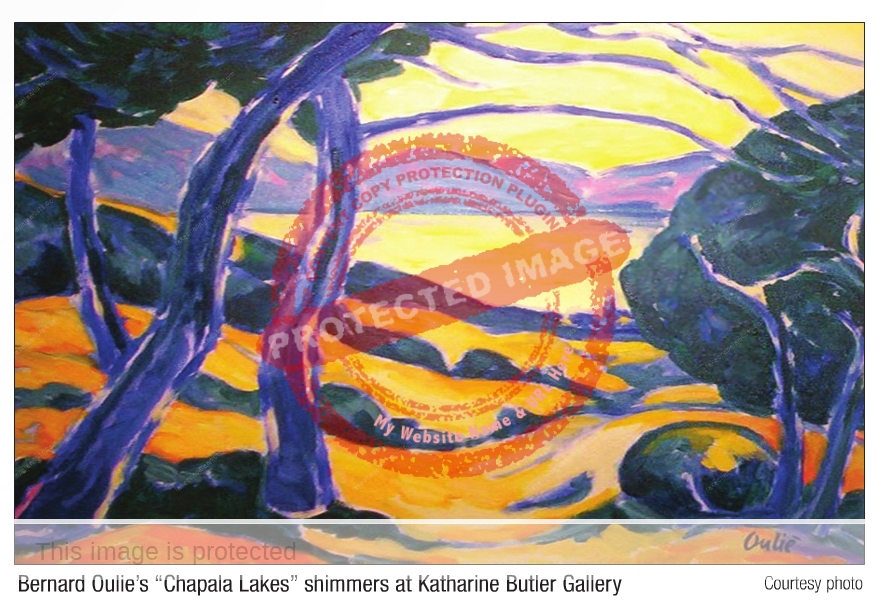

By selling the occasional painting in the Posada Ajijic, he was able to keep afloat prior to his first major solo exhibition, held in Guadalajara, at the Casa del Arte (Av. Corona # 126) in August 1954. The show opened on 2 August and was a major success. Martin exhibited 35 works – 10 paintings and 25 engravings on paper – and sold 32 within half an hour, 31 of them to a single collector from California: Hollywood movie director Archie Mayo. (The other painting was bought by a local resident: U.S.-born interior decorator Alberto Dubin.)

Local critics applauded the originality of Martin’s work. The engravings demonstrated a “method of expression at once so modern and at the same time so primitive.” Guests at the opening included Lori Fair, Nicole Vaia Langley, Anne McKeever, Jose Maria Servin and Thomas Coffeen Suhl.

Later that year, Martin sent some of his engravings north to a restaurant-store in Sausalito. A note in the 31 December 1954 edition of the Sausalito News (California) says that “some unusual paintings by an artist named Don Martin” in Ajijic are about to go on show in the Glad Hand restaurant. They are described as “etchings on cardboard with colors ‘rubbed’ into the cardboard” that “realistically depict scenes in Mexico.”

For the first half of 1955, Martin’s friend Anne McKeever was the director of the Instituto Cultural Mexicano-Norteamericano de Nayarit, A.C. During her time there, she arranged two art shows featuring his work. The first, in April 1955, was held at the Institute (Lerdo Oriente #85) in the state capital of Tepic. Martin displayed crayon and ink rubbings over woodblock prints. The opening night included a folk singing concert by Lori Fair.

The following month, many of the same works were included in the “Third Painting Exhibition, Mexican and International Artists” at the “Traditional Spring Fair” in the Public Library of Santiago Ixcuintla, Nayarit. Works by several stellar Mexican artists were on display including lithographs by Clemente Orozco, José G. Zuno, Raul Anguiano and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and drawings by Dr. Atl and Diego Rivera. The international side of the exhibition was a painting by Anne McKeever entitled “The Women”, and about 20 works by Don Martin.

Many years later, Martin’s widow, Joan Gilbert Martin, reflected that Martin’s first show in Guadalajara turned out to have a significant negative impact on the artist’s desire to exhibit his work. Initially buoyed that his paintings and engravings had received such acclaim, Martin was devastated on hearing that an appraiser in Los Angeles had dismissed his work as derivative of Paul Klee. Martin did not know Klee’s work. Though he eventually found the comparison flattering, this critical appraisal gave the artist a decades-long aversion to exhibiting more of his work.

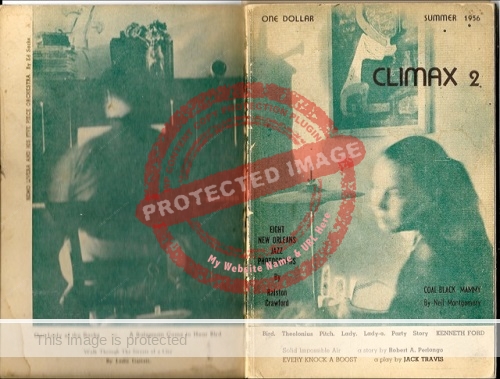

Joan Gilbert Martin has also drawn my attention to the photograph (above) used for the cover of the second issue of Climax, a Beat magazine published by Bob Cass in New Orleans and printed in Guadalajara. The photo, taken by Anne McKeever, shows Martin’s studio in Ajijic with one of his paintings hanging on the far wall. Lori Fair is sitting by the drums and George Abend is at the piano. This image neatly conveys the close friendship of these artistically-talented individuals before their paths, and lives, diverged.

In 1956, Don Martin spent about six months in the remote coastal village of Yelapa (near Puerto Vallarta) where he built a palapa house. The house itself no longer exists, but its foundations survived and are now used for the Yelapa Oasis resort‘s wellness center. Martin abandoned Yelapa when he realized that the climate was not conducive to works on paper.

Jeanora Bartlet, a mutual friend of Anne McKeever and Lori Fair, lived in Ajijic in 1957, as the partner of John Langley, and was photographed by Leonard McCombe for his December 1957 Life magazine article about Americans at Lake Chapala. While Bartlet was not part of the village art scene, she knew Martin and greatly admired his work. Bartlet, incidentally, later became the long-time partner of American pop artist Richard Hay Reagan (1929-2002) who disliked exhibitions just as much as Martin.

Coincidentally, this same Life magazine article was the reason why Joan Gilbert, Don Martin’s future wife, first visited Ajijic, and first met Martin. Gilbert and her first husband had been vacationing at the coast, “sweltering and miserable” in a “dank hotel”. On reading the article, they “immediately took off for the storied enticements of Ajijic.”

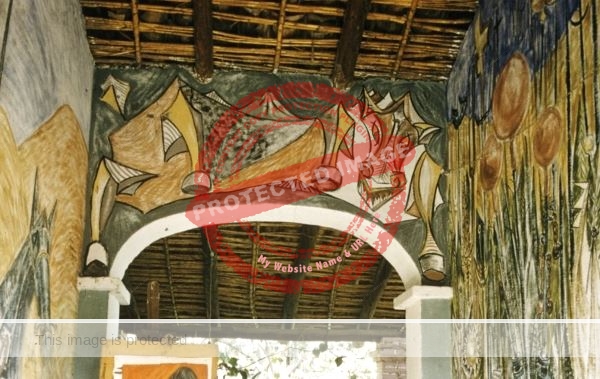

Don Martin with untitled painting. 1960. Reproduced by kind permission of Joan Gilbert Martin.

Martin left Ajijic in late summer, 1961, following a fall while painting a mural in a local gallery. The following year, an “International Exhibition”, a group show at the Alfredo Santos gallery in Guadalajara (Avenida Vallarta #1217) from 21 May to 20 June 1962 included some of his work. (Alfredo Santos himself lived in Ajijic for several years, but is best known for his evocative murals in the San Quentin prison in California: see Inside job: Alfredo Santos, muralist and painter.)

After leaving Ajijic, Martin moved first to New Orleans, where he was helped by gallery owner Larry Borenstein, and then to Venice, California. There, he re-met, and married, Joan Gilbert Martin and became friends with Beat artists Wallace Berman and George Herms.

He also renewed his friendship with author Steve Schneck, who had been living in Ajijic in the mid-1950s. In 1963, Schneck showed some of Martin’s artwork to artist Muldoon Elder, who had just opened the Vorpal Gallery in San Francisco. Elder was sufficiently impressed to travel immediately to Venice to find out more about the artist. The reclusive artist eventually agreed to a solo exhibit at the Vorpal entitled “Magic – like art – is hoax redeemed by awe”, the title of a painting that Elder particularly admired.

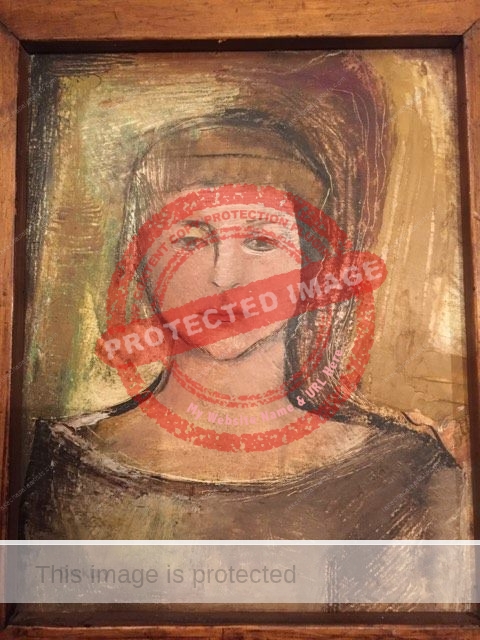

Don Martin. “Magic – like art – is hoax redeemed by awe”. 1960. (Credit: Muldoon Elder).

“I particularly admired a strange little painting set in a wine-colored velvet mat tucked into what-should-have-been-a-garish (but wasn’t) deep orange thin frame, especially after he explained that it was the recreation of an architectural drawing he had seen in an ancient manuscript that delineated the cross section, both above and below the earth, of a sacrificial temple and the surrounding courtyard. The ancient priests that had built it had found a way to inspire awe and wonderment by having the temple doors attached to rotating poles that flung the doors open as if by magic as the result of an ingenious underground device that only functioned after a large brazier in the courtyard had been ignited. The heat of the fire was devised to enter a tube that then inflated a large animal skin into a balloon-like shape that in turn tightened the ropes attached to the rotating poles and thus, as if by some mysterious force, the temple doors opened on their own and the ceremony could then begin.”

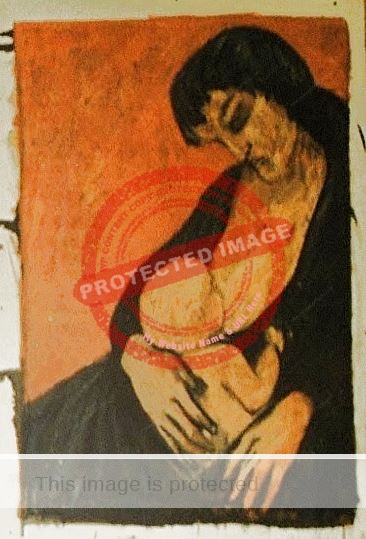

Don Martin. “He.” 1970. Reproduced by kind permission of Joan Gilbert Martin.

That painting has an interesting story but another painting by Martin, called “He” (torched spray paint & acrylic on board), is among the most reproduced paintings of its time. It was used on the cover of What Book!?: Buddha Poems from Beat to Hiphop, edited by Gary Gach (Parallax Press, 1998), which won an American Book Award in 1999.

In the 1970s, the Martin family settled in Santa Cruz, California, where Martin continued to experiment with different media and techniques. He rarely used oils, preferring acrylics and spray paint. A series of lacquer paintings in the early 1970s depicted spiritual subjects including “Buddha shapes, mandalas, guardians, heaven above and earth below, and the river as an emblem of time.” They were made by applying up to thirty layers of lacquer on a base before scraping back the layers to reveal the final image, a technique Martin had perfected during his time in Ajijic.

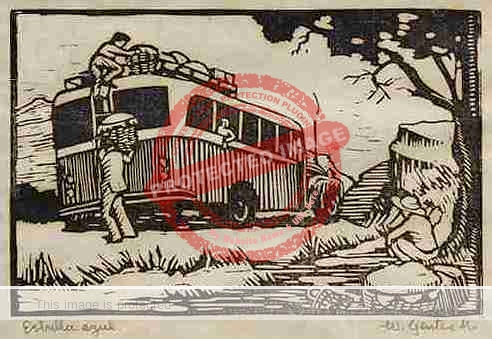

Don Martin. Twin works. “The Fish Putter”. Original in collection of Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art in Ogden, Utah. Image used by kind permission of Joan Gilbert Martin.

Influenced by his time in Mexico, Martin studied “the Codex Borbonicus, a pre-Columbian pictorial manuscript, and was inspired to produce one of his own”, in which he expressed his “personal cosmology” through a series of more than one hundred ink and wash drawings. At one time or another, Martin also explored collage, assemblage, found object art, wax rubbings, and producing “twin” pictures by blotting a painted image on another sheet before the colored ink dried.

In 1972, Don Martin’s drawing, “Magic – Like Art – is Hoax Redeemed by Awe”, was included in a group show at the College of Marin Fine Arts Gallery in Kentfield, California. Art critic Ada Garfinkel described the drawing as “irrepressible, Rube Goldberg-like”.

Don Martin also held a solo show in September 1975, “Don Martin Paintings and Drawings”, at the Cooper House Gallery in Santa Cruz, California.

Since his death in 1989, several one-person shows have highlighted this artist’s extraordinary talents. An exhibition entitled “Don Martin Memorial Exhibition” was held at the Santa Cruz Art League in November-December 1991, and also at the Canter Art Center in Healdsburg, California in March-April 1992. “Something to come home to”, a February 1995 show at the Pacific Grove Art Center, featured Martin’s paintings in lacquer and ink-wash drawings.

A major retrospective, “Don Martin: Chasing That Kite'”, was held at the Museum of Art & History in Santa Cruz, California, from May to August 1998. This show revealed the “eclectic, mystical and experimental” nature of this shy, “primarily self-taught”, artist who was reluctant to show or sell his work. “Chasing that kite” was Don Martin’s way of describing his lifelong artistic quest.

Several group shows have also included Martin’s work posthumously. These include The Pope Gallery, Santa Cruz (1994); the Pickard Smith Gallery at the University of California Santa Cruz (1994); the ReBeat Art Exhibit at the Somar Gallery, San Francisco (1996); San Francisco Center for the Book (1997); San Jose Museum of Art, California (2003-2004); the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Logan, Utah (2007-2011; 2015).

Martin’s work can be found in the permanent collections of the San Jose Museum of Art and the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, both in California, and the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Logan, Utah.

For more images of Martin’s work, see Don Martin: Maker of Things to Look At, the revised website that is a tribute to his life and work.

Acknowledgments:

My heartfelt thanks to Joan Gilbert Martin for so generously sharing her knowledge of her husband’s life and work. A special thanks, too, to Jeanora Bartlet, Geoffrey Dunn and Muldoon Elder for their helpful input to this profile.

Sources:

- Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), 20 October 1972, p 20.

- Don Martin: Chasing that Kite, 1931-1989 [website, accessed in 2016]

- Julia Chiapella. 1998. “Catching ‘That Kite’ – a peek into the mind of the late Don Martin.” Santa Cruz Sentinel, 1 May 1998, p 53.

- Prensa Libre, Tepic, 24 April 1855.

- Santa Cruz Sentinel, 3 February 1995, p 47

- Sausalito News, Number 52, 31 December 1954, p 3

Notes:

- This Don Martin is not the same person as the cartoonist Don Martin (also born in 1931) who was closely associated with MAD magazine.

- Joan Gilbert Martin, born in 1930, died in 2022.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via email or comments function.

The plot of Who is Angelina? is relatively simple. Angelina Green, an intelligent, 26-year-old, life-loving woman living in Berkeley, after the hippie phase, goes to Mexico to find herself. In Mexico City, she meets, and has an affair with, a tall, charismatic, enigmatic character named Watusi.

The plot of Who is Angelina? is relatively simple. Angelina Green, an intelligent, 26-year-old, life-loving woman living in Berkeley, after the hippie phase, goes to Mexico to find herself. In Mexico City, she meets, and has an affair with, a tall, charismatic, enigmatic character named Watusi.