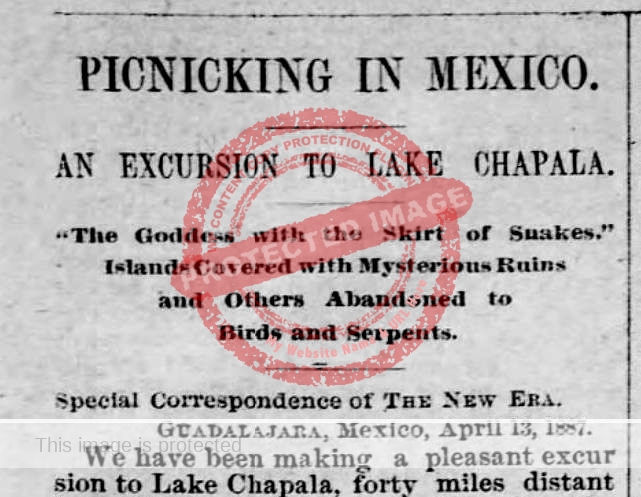

“The Sorceress: How an American Engineer was Sacrificed to the Aztec Gods.”

by Edwin Hall Warner. 1894.

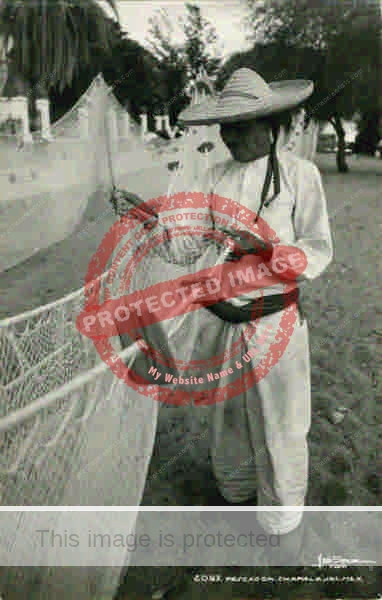

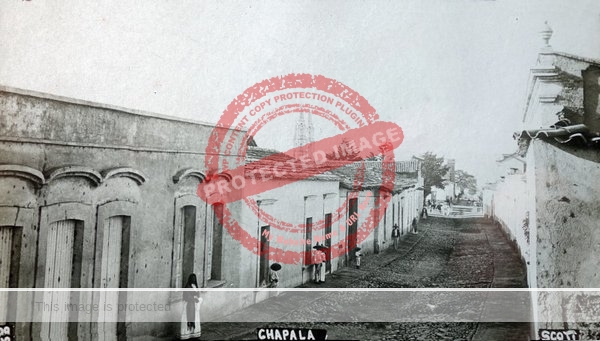

The calzada principal in La Barca runs a meandering course easterly through the town to the garita. The houses on each side are of the usual Mexican type, the more pretentious of stone, others of adobe, with barred windows and heavily doored zaguan, where the idle porter sits lazily, incessantly rolling and smoking his cigarillo, arousing himself sufficiently at times to salute a passer-by or to answer a question, and relapsing at once into his former dreamy condition. Children imperfectly clothed play solemnly in the gutter; their dark-brown bodies, shining dully through the incrusting dirt, are proof against the darkening effect of the sun’s rays; a solitary lagartija clings lizard-like to the curb and feebly resists a boy’s effort to goad him into action. The sereno leans sleepily against a corner in the shade, loosely holding his carbine, and muses on the unhappy lot of a policeman forced to keep up a semblance of watchfulness.

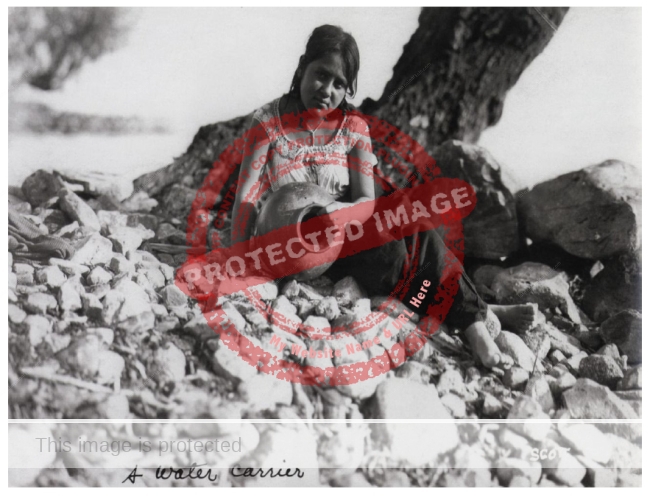

Suddenly, as a woman’s figure appears on the street, there is a chorus of shrieks from the group in the gutter and a skittering of childish feet as they disappear, panting with fright, in a dozen different directions. The porters, stirred into action, hurriedly close the doors and piously whisper an ave, the sereno draws himself erect, furtively crosses himself, and murmurs “La bruja! Dios me guarde!” as the woman passes. She moves quickly down the street, looking neither to the right nor to the left, passing the garita where the solitary customs official likewise crosses himself and asks divine protection from the wiles of the sorceress; nevertheless, he follows the sinuous, graceful movement of the young woman and notes the perfection of face and figure, which appeals to him in spite of his persuasion that her beauty is of origin diabolic and lent by Lucifer himself to snare men’s souls. She wore a piece of dark-green stuff”, folded around the hips and falling to the ankle; a jacket of red gauze clothed the upper part of her person, veiling her bosom, upon which lay a chain of gold in the form of a serpent. Her black hair, parted at the forehead and drawn back in two splendid tresses, intensified the pure white of her brow.; her eyes, shaded by long lashes, were the greenish-black of obsidian. Continuing her walk to a small adobe house some hundred yards beyond the gate, she disappeared within the doorway. The customs official gave a sigh of relief and returned to his desk.

Once within the house, she lost her firmness of bearing, tottered to the center of the room, and sank in a heap on a rush-mat. Her form suddenly grew rigid, her face took on the gray pallor of death; the eyes became set and stared fixedly at the wall opposite; the golden serpent on her bosom seemed in the half-light of the dying fire to writhe and twist, instinct with life.

– –

At the fire sat a little, shriveled-up old man, brown and wrinkled, stirring with skinny claw the contents of an olla. Of her entrance he had taken no notice, continuing his employment as if waiting for her to speak. At length he looked around and sprang to his feet; a pallor almost as deep as her own overspread his face. “Maria!” he whispered; “Maria!” Meeting with no response, he hastily moved to the door, barred it, and, returning to his place by the fire, crouched down and shrouded his face in his arms.

Soon the woman’s body lost its rigidity, her eyes turned toward the doubled-up figure of the old man and shone with such a basilisk glare that he moved uneasily; the eyelids drooped, and she sank back upon the floor, apparently asleep; her respiration, at first harsh and labored, became quiet and regular.

The old man now raised his head for the first time, and fixed his bright, beady eyes on the woman’s face.

“A prophecy,” he said — “a prophecy! Let the high priest of the gods know their will!”

As if in response, the woman began an inarticulate murmur. Soon her voice rose to distinctness :

“The darkness of earth is in the temple; the altar of the lire-god is black with ashes, the serpent lies dead before Quetzalcoatl; the grinning skulls at the feet of Xipe-totec mock the power that is gone forever; the snake-skin drum is beat in vain; the victim is slain; the sound of thunder fills the temple, the priests fall dead, and the foot of the white man desecrates the house of the gods.”

Her voice fell, and, with a fluttering sigh, she awoke. The light of expectancy which had illuminated the old man’s face gradually died out as the woman’s words fell on his ear, and, at their conclusion, he seemed shrunken to half his size.

“‘Tis false!” he said — “false! The power of the gods can never fail. For seven years have we awaited the sign, and to-morrow Xipe-totec, gladdened once more by the sight of blood on the sacrificial stone, will make answer to his children’s prayers. Saw you the white stranger again today, Maria?” he asked.

“Yes; I have but now left him.”

“And he will be in the barranquilla to-morrow at sunset?”

The woman’s voice faltered as she answered: “Yes; if—”

“If!” hastily returned the old man; “if? What does this mean?”

“He will come if I send him word, but — but I cannot — oh, papa mío, don’t ask it. Forego the sacrifice to Xipe-totec, and content the people with the sacred mask-dances.”

He looked at her with astonishment: “Seven years have we waited, and the daughter of El Viejito, the high priest, asks that the sacrifice be omitted! What woman’s whim is this?” he said, fiercely. “Why should the god, upon whose awful power we must depend, be denied his due?”

“He loves me, father.”

“Loves you! And if he did not, could he ever be lured within the reach of the Nagual priesthood? Suppose he does, he will pay the penalty of his folly.”

The woman rose to her feet. “He shall not,” she said, firmly: “for I love him, and no priestly knife shall ever harm him. At first, I believed all you had taught me; believed that my duty to the gods made all things good, no matter how cruel and horrible they otherwise seem. But now I know better. The ancient religion shall die out and the worshipers perish from off the face of the earth ere harm shall come to him I love.”

The fierce glitter in the old man’s eyes gave way to a look of crafty cunning. “Well, well! so be it,” he said; “the sacred dances must answer.”

– –

When the “Golden Ass” — as his La Barca neighbors unpleasantly called him — developed a taste for mural decoration, his case was a serious one; the casa pintada was the result, and a most marvelous one it is. His zeal in the cause of art was intense, but not discriminating : primary colors alone seemed to fill the requirements; minor details of perspective, truth to nature, and the like, were absorbed in a wild hunger for color, and plenty of it. Impossible

landscapes and oddly constructed animals ran riot on the walls.

He is long since dead; but his house remains, and made very comfortable engineering head- quarters. In one of the least violent rooms, overlooking the miniature fountain in the patio, the engineer in charge, Vincent Colby, had his office. He was a good type of the American engineer : tall and well built, he gave the impression of staying qualities rather than of muscular power. The warmth of a tropical sun had but slightly deepened a naturally fair complexion; his dark hair and good eyes, with a softness of intonation and engaging manner, stamped him at once with the Mexicans as muy simpático, and revealed to them the possibility that all Americans might not be barbaros, an impression unfortunately yet not unnaturally prevalent.

Just now Vincent was in an unpleasant frame of mind, and his musings ran somewhat as follows: “I may be an idiot, but I can’t help it. Idiocy may be congenital or acquired — mine must be acquired, for, up to date, I’ve been reasonably conventional. The mater will rave, I know, when I take home a native wife; the sisters will make matters unpleasant for a day or two; and the governor will probably cut up rather rough. But if I’m suited, they will have to be; if a man can’t make his own choice when it comes to marrying, when can he? I’ve made mine — if she’ll have me, that is. There’s the rub. She says she’ll give me an answer on the seventh — why not the sixth or eighth, I don’t know. I’ve asked her a dozen times in the last ten days, but it is always the same : she neither says yes nor no. It can’t be coquetry, for she smiles sadly, yet with a wistful look which can mean but one thing.”

Here a rattle of hoofs in the patio interrupted him, and he looked out to see the company’s doctor dismount.

“Hello, doc,” he called out, “come in here; I want to talk to you. There’s not a soul about the place, and I’m too lazy or nervous to work. Throw your saddle-bags over there on the table and have a drop of toddy. No? You don’t usually let a good thing go by. What’s up? Patients dying or getting well, or have you been rowing it again with the padre at Penjamo, because you differ as to the use of water? You’re all wrong. Be satisfied to cure the poor beggars without lecturing them on the advantages of an occasional bath. To clean them is so radical a measure that you’ll be run out of the country as a pernicious foreigner attempting to demolish a most cherished idea.”

The doctor made no reply.

“Well, out with it, doc. You needn’t look at me like that.”

“Vince, we’ve known each other as boys and men for a good many years ”

“All right, doc; you always begin with gentle boyhood days when you’ve anything particularly damned unpleasant to say. But I suppose I must submit. I don’t know what’s up, but if it’s as serious as you look, old man, it’s pretty bad.”

“It’s serious or not, as you choose to make it,” answered the doctor. “An ambition to acquire the Mixe language may be a laudable one; folk-lore, ancient religion, and all that sort of rubbish learned on the spot are a kind of relief in this hot, dusty hole, though I don’t care for it myself.

Even Nagualism and other high-class sorcery may be amusing to you, if not to me. But when you get spoony on the sorceress herself, it’s time for some one to open your eyes.”

“Sorceress! ” responded the other. “What rot you are talking. That sort of thing is played out in these days.”

“I tell you it isn’t played out,” rejoined the doctor; “the natives keep it dark and say there’s nothing in it, but half the Indians in this town hold to the old faith, and every time a child is baptized, they set up a little incantation business on the sly and do the trick over again in their own way, with an extra curse or two on the white man and his god. I scared the story out of old Sebastiano, and got the whole programme. The Eleusinian mysteries aren’t in it with this accursed Nagualism, which includes human sacrifices and other pleasant little ceremonies which, though no doubt highly gratifying to the worshipers, must be somewhat unpleasant to the victim, I fancy. El Viejito is the high priest, and Maria Candelaria is his daughter. They are a dangerous, fanatical lot, and if you’ll take my advice, you’ll leave them alone. They bitterly hate the whole white race, and an offering from it is not only an act distinctly pleasant in itself, but it is a religious duty as well. The government has only been partly successful in keeping it down, for, as an organization, Tammany Hall is chaos compared with it. They practice their devilish rites once in so often, and some one disappears.”

To hear one’s best beloved spoken of as a sorceress, and as one to whom wading in human gore was a usual and agreeable employment, was, to say the least, irritating; but the doctor’s earnestness and evident belief in what he had said roused in Vincent a strong desire to laugh.

“You’ve been imposed upon, old man,” he said. “Haven’t you learned yet that the one delight of the native is to impose on the credulous with creepy stories? Moreover, you have allowed yourself to listen to gossip about the

woman whom I intend to marry.”

“Marry! My God!”

“Yes, marry — if she’ll have me. I intended speaking of it, when you commenced with your infernal nonsense. It’s my affair anyhow, and if I’m satisfied, you can’t complain.”

To be told, even indirectly, to mind one’s own business is particularly hard, when one has tried to do a friend a kindness, so the doctor left the room, offended at the manner in which his efforts had been received.

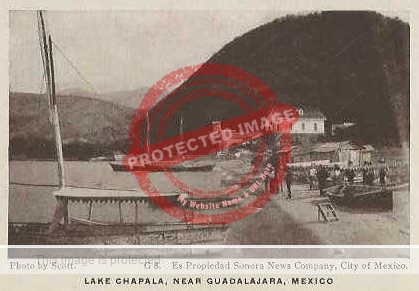

The sun was low in the west on the following afternoon when the doctor rode into the patio of the casa pintada. His progress through the town had been delayed. First the alcalde had stopped him, and the usual salutation had extended into a conversation in which the alcalde was set aright in a problem which had occupied his mind for some time. He gave the Americans credit for exceeding ingenuity, but was as yet unadvised as to how even they could dig holes and set telegraph-poles in the bottom of the sea, upon which to string the submarine cable. The sea, he was aware, was, in places, much deeper than Lake Chapala. The simplicity of the method increased largely his admiration for the race whose resources of mind enabled them to cut loose alike from precedent and telegraph-poles. The padre next invited his attention to the beauty of a pair of kittens playing in a doorway, and was anxious in his inquiry as to whether a benignant Providence had vouchsafed to the land beyond the Rio Grande the blessing of cats. Having gently assured him that impartiality had been shown in the matter, although there were points about Mexican cats which other nations might envy, the doctor was free to make his way to head-quarters.

A nameless fear had oppressed him and could not be shaken off. He went hastily to Vincent’s room, but found it vacant. He was about to call a servant and inquire as to the whereabouts of his friend, when he saw a small scrap of paper on the floor. Idly picking it up, he read what aroused again his fears of the previous evening. In green ink, on paper none too clean, with vs and bs used interchangeably and double l doing service for y, was written: “Meet me in the Barranquilla de Homos at sunset. Maria.”

Hastily calling for Julio, he was told Vincent had left at five. Julio had been ordered to unsaddle his own horse, as his services would not be required. Returning to his room, the doctor consoled himself with the idea that, although a tryst ten miles away was unusual, danger was not necessarily impending; the roads were fairly free from bad characters, and a lonesome ride was probably the worst to be expected.

He had brought himself to this state of mind when a woman staggered into the room.

“Save him! Save him, doctor/” she cried. “Save him! ”

Her hair fell in a tangled mass about her face, her clothing was torn and disarranged, and her wrists cut and bleeding. He recognized Maria, but her presence made the meaning of what he had read unintelligible.

“I refused to send for him,” she continued, hastily, “so they bound me in the casita and sent him a message in my name. They left me powerless, as they supposed, but I escaped.”

“They? Who are they? ”

“The priests of the Nagual; they who cling to the old faith, and who, even now, would sacrifice on their altar the man I love. Ah! doctor, make haste or we shall be too late; an hour at most is all we have.”

Ordering Julio to follow him with the horses, the doctor made his way to the barracks.

Don Juan Gomez, Captain in the Fourth, was a model cavalry officer and a warm friend of. the engineer’s. The doctor had scarcely commenced his story, when Don Juan gave a brief order to his orderly at the door. A bugle call rang out, a clatter of hoofs on the pavement and the rattle of sabre and carbine in answer, gave proof of the discipline of the troop. A sergeant entered and saluted.

“Listo, señor! A caballo, doctor!”

With Maria as guide, they dashed out into the night. In the service of a friend, Juan Gomez spared neither man nor beast. The breath of the horses came hard and fast, and spur was freely used before Maria said : ” The entrance is between the two bowlders to the right of the stunted pine.”

Sunset found Vincent in the barranquilla. He had given no thought to the strangeness of such a place of meeting; he was to see again the woman he loved, and that was sufficient. No idea of danger had presented itself. Strong and well armed, he was confident of his ability to take care of himself. The place was dark and dismal, and he was too absorbed in his own fancies to note even casually his surroundings.

The trail had narrowed to barely a sufficient width for his horse, when he saw three men approaching on foot. They stood aside as he came up, and, as he attempted to pass, one seized him by the foot and threw him out of the saddle. Before he recovered from the shock, he was pinioned, blind-folded, and helpless. He felt himself lifted up, carried some little distance, and placed on the ground again.

He remained thus for an hour or more, when the bandage was removed from his eyes. He had felt no especial fear at his treatment, believing it to be a question of a small ransom and liberty as soon as he could communicate with his friends. He opened his eyes, and with the first glance around, all idea of liberty by purchase departed at once. As his eyes became accustomed to the semi-darkness, he saw he was in a cave-temple. On his right was a wooden idol, standing on a low stool. It was black and shining, as if charred and polished; its look was grim, and it had a wrinkled forehead and broad, staring eyes. He had read of the Black King, and now saw himself face to face with him. On the left was a coiled serpent, with head erect, shining eyes of jet, and fancifully painted scales, which he knew represented Quetzalcoatl. Immediately before him stood Xipe-totec, “the flayer of men,” the representative of all that was vile and horrible in the hidous cult whose victim he was. In front of the idol stood the sacrificial stone, humped in the centre, the better to present to the knife the chest of the victim.

His heart sank within him as he read his awful position in the signs around him. The wealth of the world would not save his life from the fanatical faithful of the Nagual sect. But last night he had declared the practice of their rites obsolete; now he had full proof of his error, and was about to pay the penalty.

By this time the cavern had filled with people. Half-naked priests began a low chant in a minor key, circling in front of the idols and swinging terra-cotta censers, from which were emitted the pungent fumes of copal.

The movement became faster, their voices rose in their excitement, while, in their frenzy, they gashed themselves with knives until the blood flowed freely. Seizing Vincent, they placed him, face upward, on the sacrificial stone.

The high priest stepped forward to the side of the victim. Raising his knife of green obsidian above his head, he began : “Xipe-totec, the all powerful.”

A woman’s shriek rang out, a flying form reached the altar as the knife descended, and a roar of musketry reverberated through the cavern.

A woman lay dead at the side of the sacrificial stone, on which rested the body of a man, an obsidian knife driven home in his heart.

Edwin Hall Warner.

San Francisco, July, 1894.

First published in The Argonaut (San Francisco), 9 July 1894.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

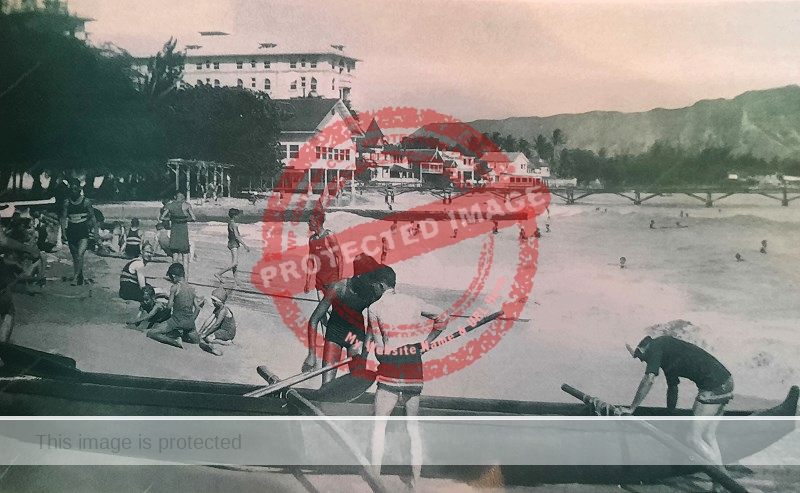

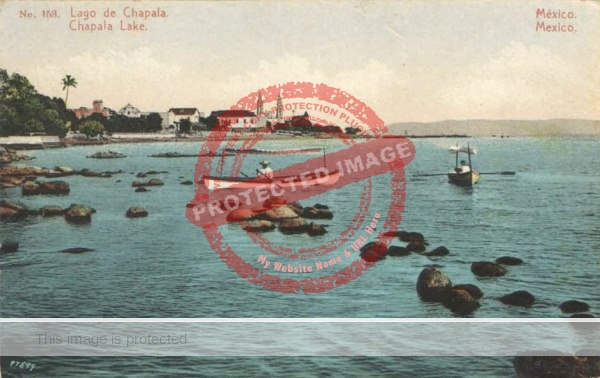

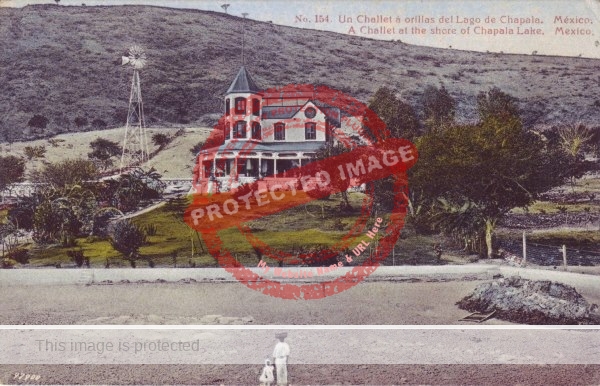

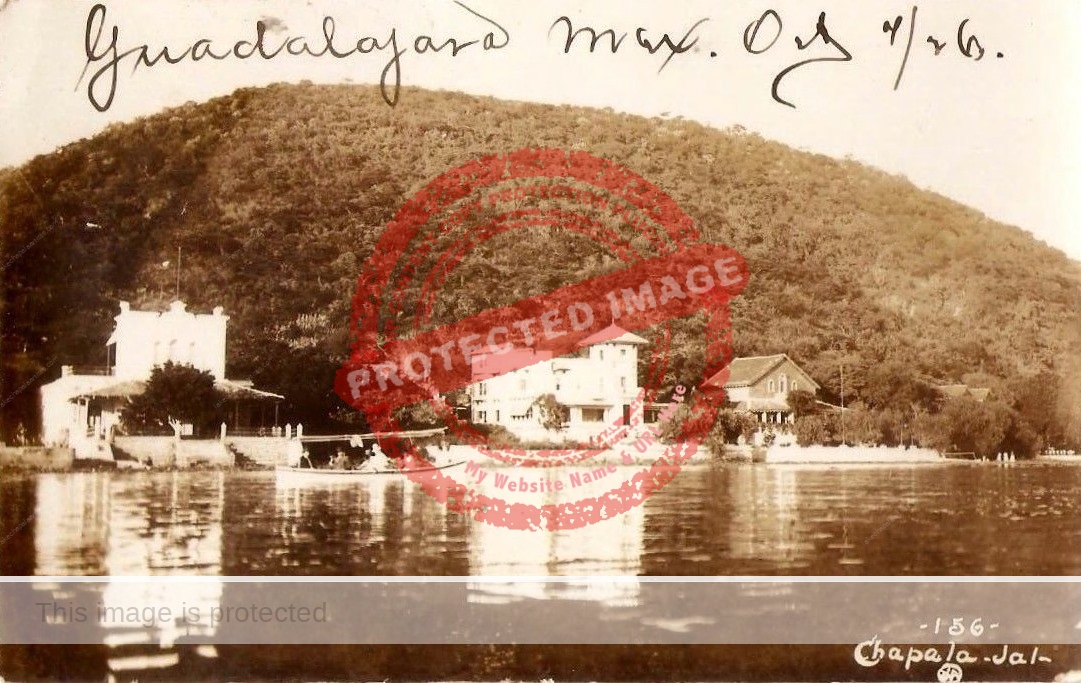

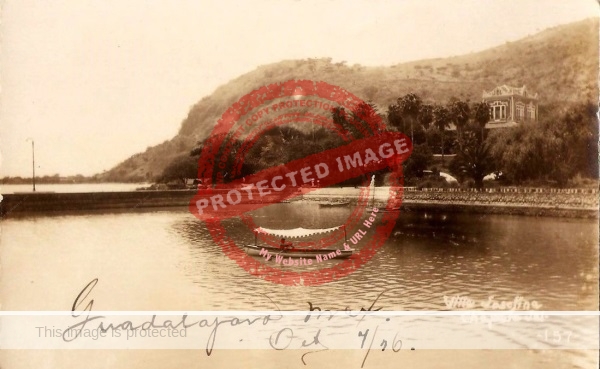

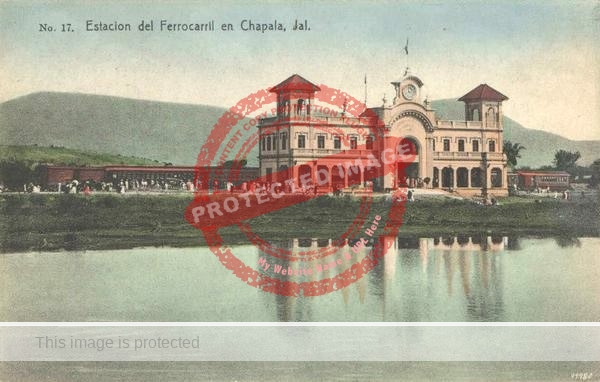

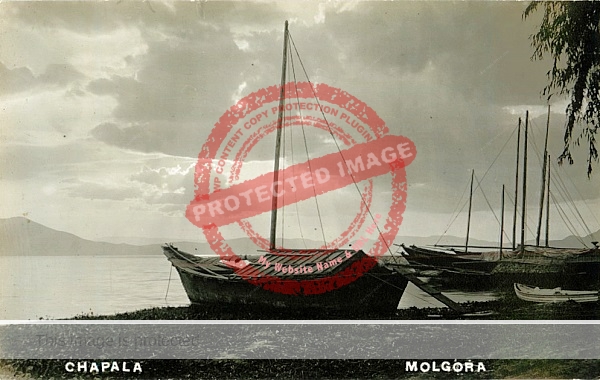

Learn more.Lake Chapala: A Postcard History (2022) uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala first became an international tourist and retirement center.

Source

- Edwin Hall Warner. 1894. “The Sorceress : How an American Engineer was Sacrificed to the Aztec Gods.” The Argonaut (San Francisco), Vol. XXXV. No. 2 (July, 1894), 4.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.

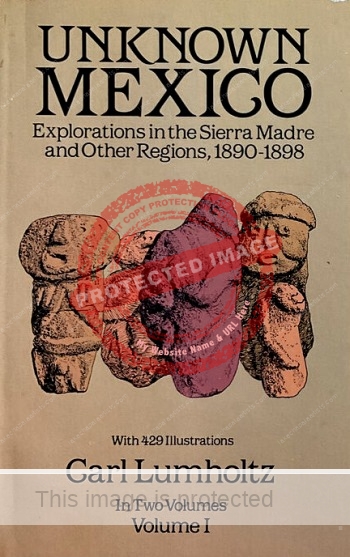

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.