Bethel Young extolled the virtues of Chapala in 1941 in an article entitled “In Mexico,” published in Mexican Life.

In the article, she claimed to have fallen in love three times in the 37 days that she and her husband, Lafayette Young III, had spent in Mexico: first with the inscrutable Indian housemaid employed by a friend in Mexico City; then with José, “a slight little lad who… languorously sells coca colas, orange and lemonade on the beach at Lake Chapala”; and thirdly with Lake Chapala itself.

She struck up a friendship with José shortly after they first met on the beach:

During my first day on the beach, stretched luxuriously like a cat before the hearth, in my reclining chair in the sun, this boy in his big straw hat came trudging by, carrying a bucket filled with bottles, water, and an infinitesimal piece of ice… Toward sundown I was on the sand again lazily watching the mountains around the rim of the lake settle in to the shadows, when lo! from nowhere, apparently, José appeared.”

The Youngs were staying at the Hotel Arzapalo and José quickly became a frequent visitor to their room, to inspect some of their possessions—typewriter, sunglasses, letter knife, “scuffed house shoes that have fur trimming”, a cigarette case and a lighter—and to look at pictures and books. Before long, José was emptying their ashtray and taking their letters to the post office, in exchange for insignificant hand-outs and the occasional ice cream cone.

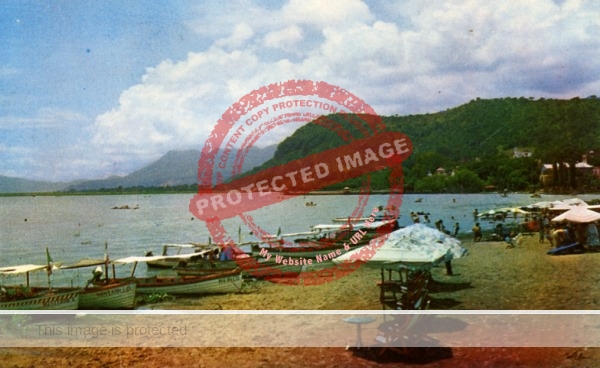

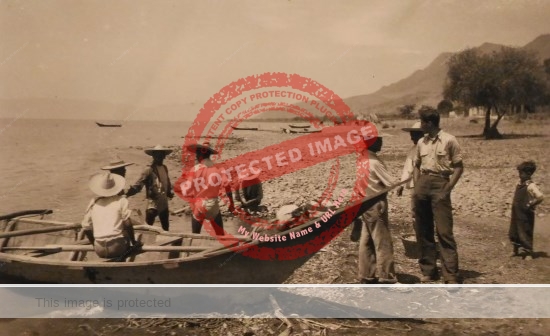

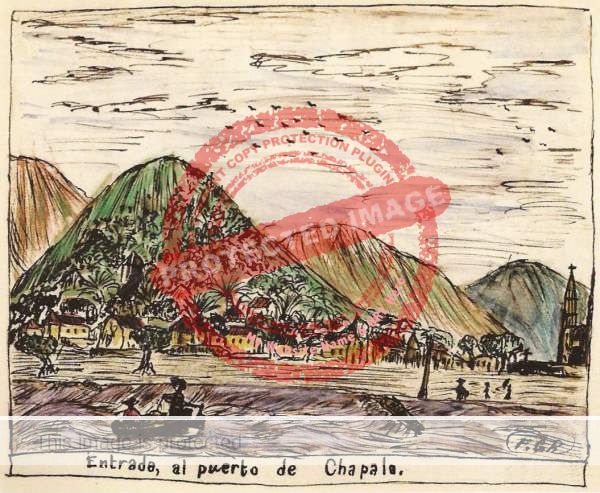

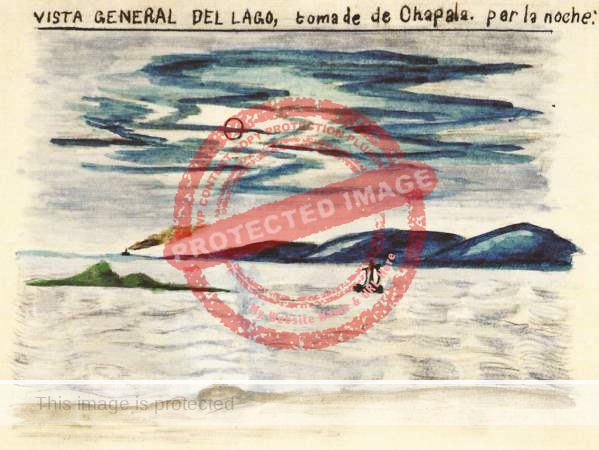

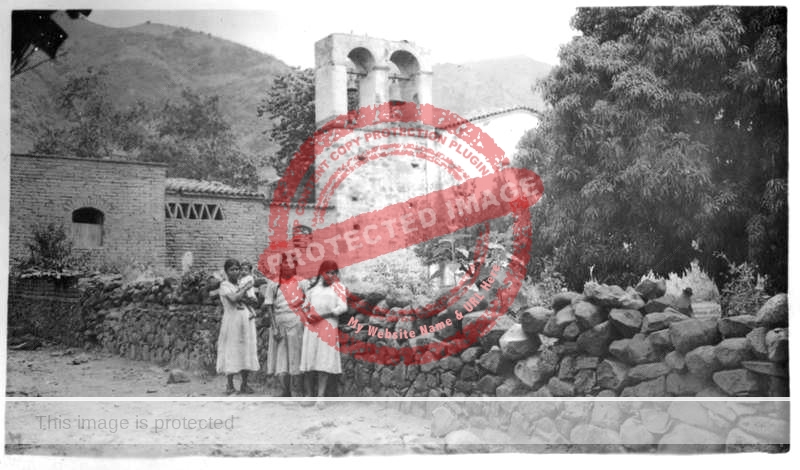

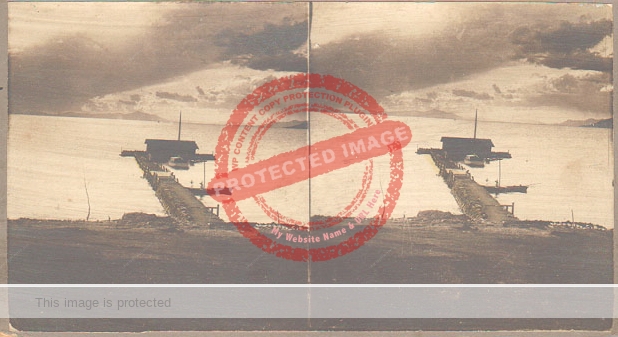

Lake Chapala, ca 1941. (Photo believed to be by Herbert Johnson); all rights reserved.

As for her love affair with Lake Chapala, it’s probably best if Ms. Young speaks for herself:

My third love is a poem, a painting and a symphony, sometimes animated, sometimes quiet, always beautiful. I am in love with the Lago de Chapala, its picture frame of mountains to the south and roof of cobalt blue and snow-white cotton puff clouds. The lake’s milky blue-grey water smoothness is cut by ponderously moving launches, antedated, clumsy crafts that ply between our own Chapala village dock and other, more inaccessible Indian villages. Large rowboats with rigged up white awnings, and the small single oar lock boats, bob at the water’s edge tethered to a crude plank dock. Once or twice each day a graceful sailing canoa quietly slides past, quite far out from shore, The brown-black hulls, with high proud prows and the aged white sails, might well have sail ed right out of Greek mythology, or at least out of Columbus’s venturesome fleet. The canoas are fishing boats from which the fishermen throw their huge circular handwoven nets, to snare small schools of charales—edible fish only four or five inches long. Or they are used to transport “freight”, wood, melons and vegetables.”

Difficult to imagine a better description!

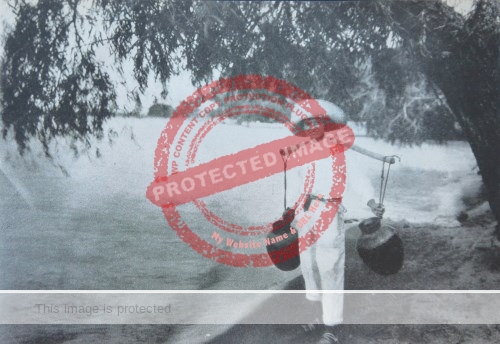

At that time, Chapala still had no municipal water supply:

Native women carry drinking water from a spring that has been piped, in red earthenware jars balanced on the right shoulder and lightly steadied by the right hand—a water-carrying pose that has gone unchanged for centuries.”

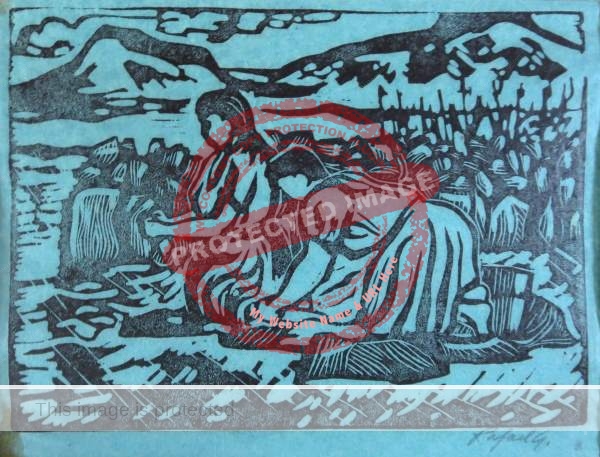

After doing the family laundry at “a small rocky cove,” these same Indian women took time for a leisurely bath:

The women set aside their dark petticoats and dresses and emerge in a modest white cotton camisole which reaches to the knees. With black braids swinging long, they wade slowly in the shallow water and at the desired depth, sit down, lather and rub as if the rockbound cove were a luxurious bath tub filled to the brim with warm water. With crude wooden dippers or dented tin pans they lift quantities of water above their heads and spill it like a shower.”

After washing themselves, they scrubbed and bathed their children.

Lake Chapala, ca 1941. (Photo believed to be by Herbert Johnson); all rights reserved.

Ms Young ended her piece with a word of caution as regards the future.

Chapala is a new frontier. The single asphalt pavement ribbon that connects the village to civilization has only been completed for three years. For only one year has electricity been available. There is still no water system, no paving in the town other than the cobbles. However, I fear, Chapala’s pristine beauty will soon be tarnished by modernity, and her lovely slow life-tempo will be accelerated to accommodate American tourists.”

Just who was Bethel Young?

Bethel Louise Young (née Johnson) (1916-1975) was born in Iowa and studied at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. She married Lafayette Young III in 1939. “Lafe” Young III (1914-1981) owned the Bargain Bookstore, a hub for paintings, poets and artists of all kinds, in San Diego. Young was a close associate of Henry Miller, responsible for delivering books to him. The two men regularly corresponded and much of their correspondence from the period 1951–1976 is now held in the Jane Nelson and Lafayette Young Collection in the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur, California.

Following the trip with his wife to Chapala, Young produced two typescript 174-page copies of “Letters from Chapala” (1941). One, dedicated to Henry Miller— “These letters are written and dedicated with highest esteem to Henry Miller, a great writer, a greater man,”— now resides in the Henry Miller archives at UCLA; the other was given to the author’s mother.

Miller himself included “Letter to Lafayette” as a chapter in his The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. In the chapter, he recalled meeting “Young Lafe” just before he (Lafe) was about to depart for Mexico:

In a short while Lafe will pack his bag and go to Mexico, there to write a book on Norman Douglas or Henry Miller, of which he will publish just two copies, one for this subject and one for his family – just to prove that he is not altogether worthless.”

Writing genes were passed down in the Young family. Their daughter Nicole is the author of Child Caring (2010) and Nicole’s daughter, Molly Young, is the author of “Charles Bukowski, Family Guy,” a fascinating essay about the famous German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer.

Sources

- Kappa Alpha Theta Journal, Vol. 53 no. 3.

- Henry Miller. 1945. The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. New York: New Directions.

- Bethel Young. 1941. “In Mexico.” Mexican Life, Sept 1941, p 15-17; reprinted in The Des Moines Register (Des Moines, Iowa), 19 October 1941, 37; and in Zlexiran Life magazine

- Molly Young. 2010. “Charles Bukowski, Family Guy.” Essay on poetryfoundation.org

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Szekely was born in Máramarossziget in what was then Hungary (now Romania) on 5 March 1905 and died in 1979 in Costa Rica.

Szekely was born in Máramarossziget in what was then Hungary (now Romania) on 5 March 1905 and died in 1979 in Costa Rica. For Biogenic living, Szekely argued that people’s daily diet should consist of 25% biogenic foods (life renewing; eg germinated cereal seeds, nuts; sprouted baby greens); 50% bioactive foods (life sustaining; eg organic, natural vegetables, fruit) and 25% biostatic (life slowing; eg cooked and “stale” foods). They should avoid biocidic foods, such as processed and irradiated foods and drinks, since these were “life destroying.” In addition to this diet, Biogenic living also includes meditation, simple living, and respect for the earth in all its forms.

For Biogenic living, Szekely argued that people’s daily diet should consist of 25% biogenic foods (life renewing; eg germinated cereal seeds, nuts; sprouted baby greens); 50% bioactive foods (life sustaining; eg organic, natural vegetables, fruit) and 25% biostatic (life slowing; eg cooked and “stale” foods). They should avoid biocidic foods, such as processed and irradiated foods and drinks, since these were “life destroying.” In addition to this diet, Biogenic living also includes meditation, simple living, and respect for the earth in all its forms.

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.