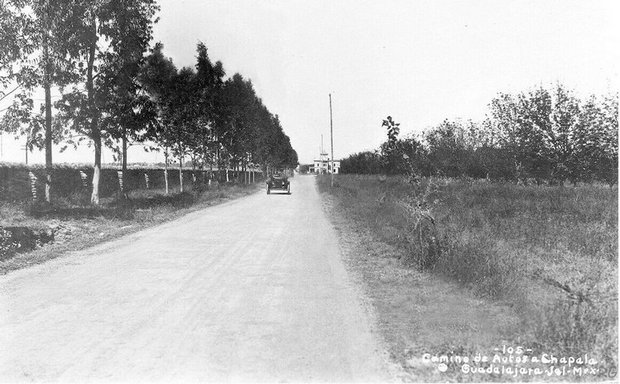

Several Mexico City-based photographers visited Chapala over the Easter period in 1908 to ensure that President Porfirio Díaz’s visit that year was adequately covered in the national press.

One of the more noteworthy was Heliodoro J. Gutiérrez, who was sent there by El Tiempo Ilustrado, which included about twenty of his photographs in its 26 April 1908 issue. Many of the photographs show high society Mexico City families and their children enjoying their vacation at the lake. It was clearly far more important for Gutiérrez, who specialized in portraiture, to capture the faces and poses of some of Mexico’s high society, rather than portray Chapala’s scenic and architectural beauty.

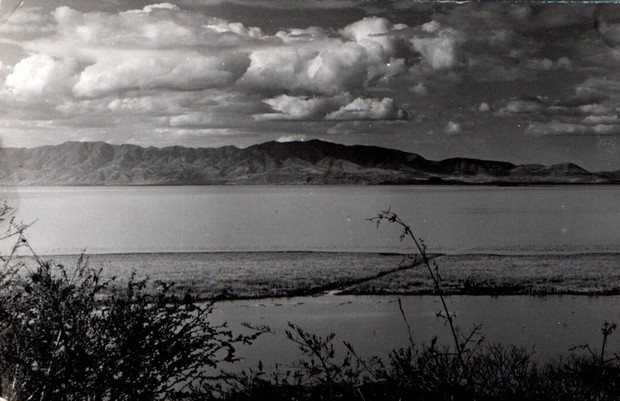

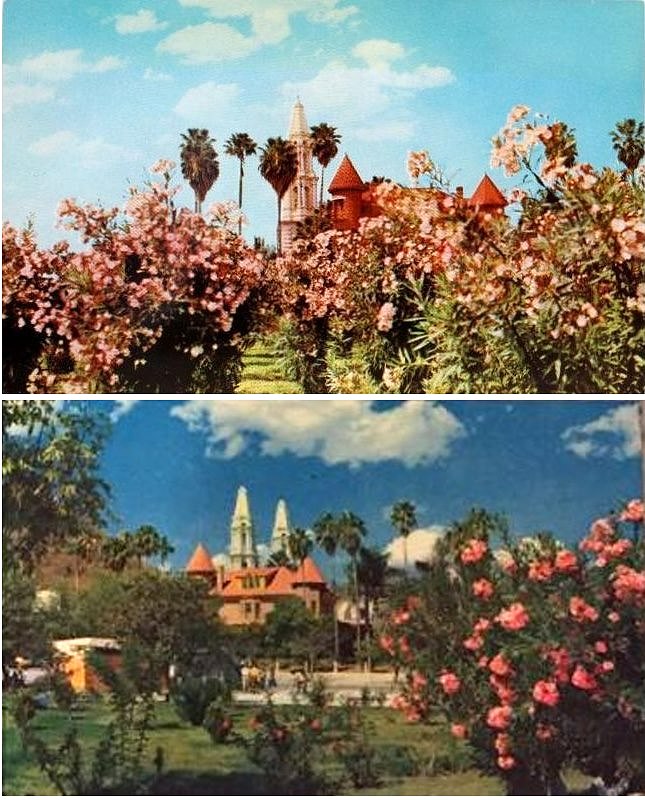

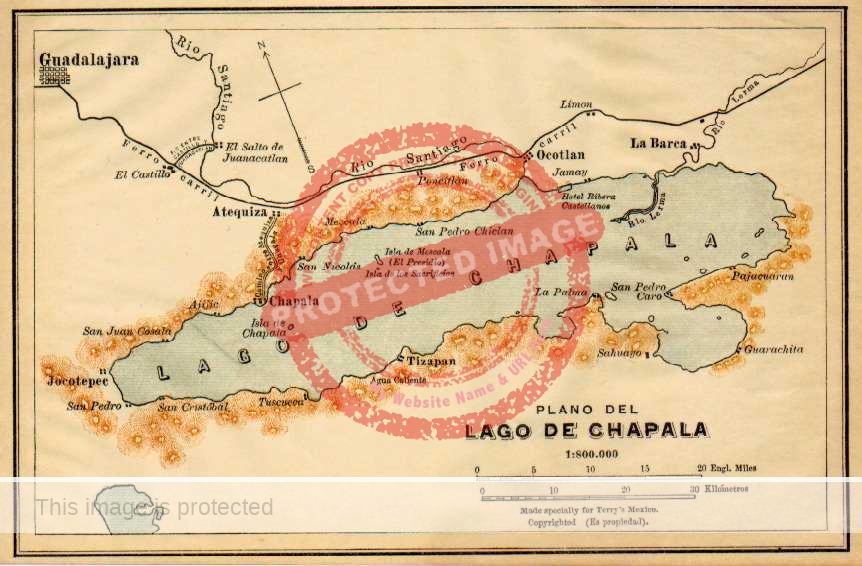

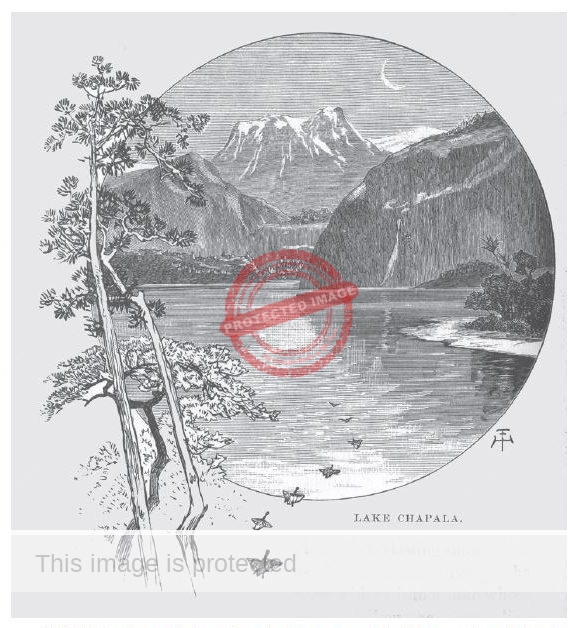

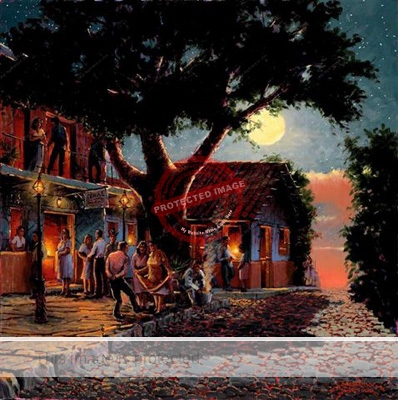

El Tiempo Ilustrado summarized some of the events that had taken place that Easter in Chapala. They included moonlight strolls along the beach, a bullfight organized by Alberto Braniff in an improvised ring, a regatta, a formal dance at the Hotel Palmera (following which the younger people serenaded the chalets, hotels and private houses until daybreak) and excursions to lakeshore villages. Following one of those excursions, the magazine reported, the passenger vessel Carmelita had capsized while returning from Ajijic.

Aside: The Carmelita had been brought to the lake by the Crompton brothers in 1900. The small Wisconsin-built “electrical yacht” was named after President Díaz’s young wife (the sister-in-law of Lorenzo Elizaga, who owned El Manglar estate to the west of Chapala). The Cromptons sold it to the Lake Chapala Navigation Company in 1904. It capsized on 18 April 1908, throwing 14 passengers into the water. Other boats rushed to the rescue and no lives were lost. Two years later, the Carmelita repaid the favor when it rescued the passengers of the steamer Elisa after she lost power near Ocotlán.

The magazine told its readers that Heleodoro (sic) Gutiérrez—an ‘intelligent artist’—was offering more than thirty photographs—landscapes, groups and portraits—to the public, either as a set or individually, from his studio, The Chicago Photo Studio at 2a de Nuevo México #32. Alternatively, readers could make arrangements by telephoning Ericson 1085.

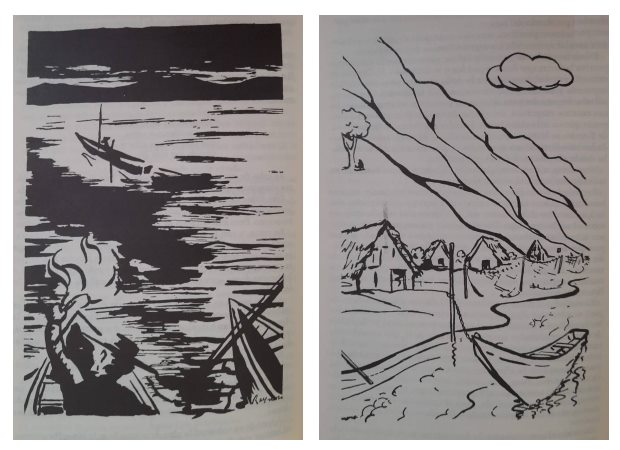

H. J. Gutiérrez. 1908. Lorenzo Elizaga and Manuel Cuesta Gallardo in the latter’s boat. El Tiempo Ilustrado, 26 April 1908.

The Chapala photographs included this one of Lic Lorenzo Elízaga and Manuel Cuesta Gallardo. According to the original caption, the boat belonged to Cuesta Gallardo. However, curiously, a few months earlier El Tiempo had reported that a new vapor (steamer)—jointly owned by the two men and named Chapala—had just been launched on the lake. Even though the photo does not appear to show a vapor, perhaps the term was used loosely and this is the same boat.

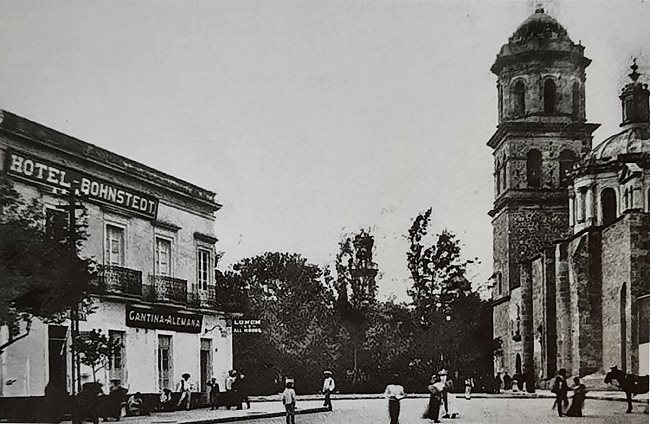

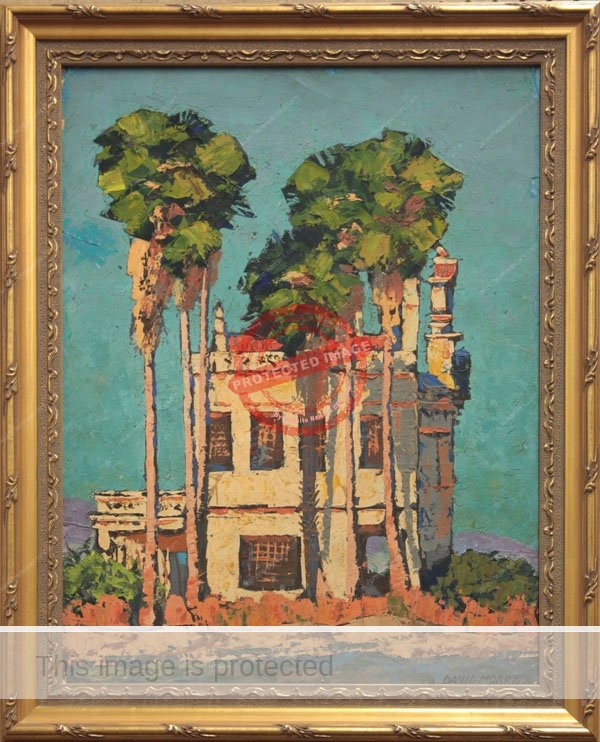

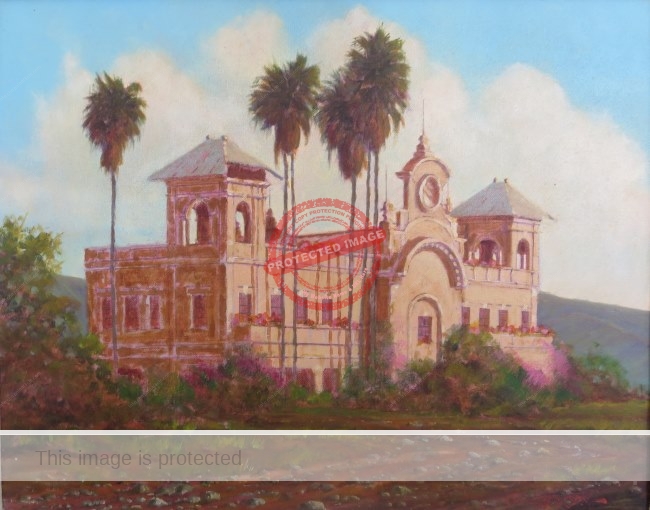

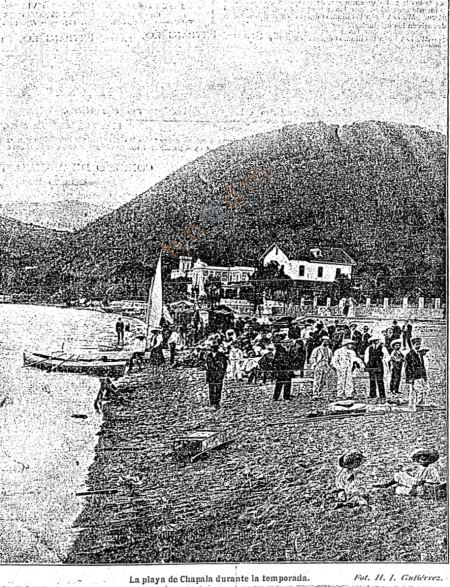

Gutiérrez’s photographs also included several portraits of children in the Limantour, Casasús, Araico and Rivas families, a portrait of Sra. Robles Gil de Collignon, and a number of views: of the town from the lake, and of the pier, the main beach thronged with people and boats, a sunset, the Braniff ‘chalet’ and the Hotel Arzapalo. Unfortunately, the only good quality version I have found of any of these photographs (some of which were republished by El Tiempo Ilustrado in later years) is the one of the boat. If anyone has access to high quality scans of any of the other Chapala photos, please get in touch!

Researcher Arturo Guevara Escobar has published an extended multi-part biography of Gutiérrez (in Spanish). According to Guevara, Heliodoro Juan Gutiérrez Escobar was born in Zacoalco de Torres, Jalisco, on 21 December 1878 and died in Mexico City in 1933.

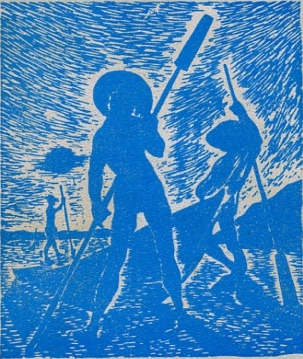

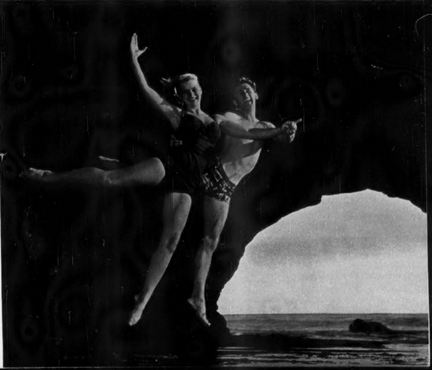

H. J. Gutiérrez. 1908. Playa de Chapala. El Tiempo Ilustrado, 23 April 1911. Note: this is a cropped version of a photo originally published in the 26 April 1908 edition. Credit: Hemeroteca Nacional de México.

Gutiérrez learned photography while living in San Francisco for six years from 1896 to 1902. He returned to Mexico in 1902 and opened his first photographic studio in Mexico City (the first of many he established during his lifetime) in 1906, the year he married María Luisa Vélez López from his home village of Zacoalco.

Before long, Gutiérrez employed an uncle, Aurelio Escobar Castellanos, as his assistant. As the photographic business expanded, Gutiérrez took on several other family members, male and female, to help. His wife assisted with administration and was the firm’s legal representative. Both their sons—Benito (born c 1913) and Luis (born c 1916)—also became photographers. The family resided in Mexico City, but by the time of Luis’ marriage in Mexico City in 1948, his mother had returned to live in Zacoalco.

Gutiérrez succeeded in keeping his photographic studios active during the revolutionary period, became president of the Asociación Mexicana de Fotógrafos de Prensa (Mexican Press Photographers Association), and helped establish (in 1926) the Mexican Photographers Association. He and his assistants took photographs of many of the most notable events and figures of the time, including Emiliano Zapata, the Battle of Ciudad Juárez (1911), the Ten Tragic Days (1913) and the Cristero War (1926-1929).

Note: Many decades later, Aurelio Escobar Castellanos’s personal collection of two thousand negatives, more than 360 positives, and cameras was donated by his family to the National Photo Library of INAH (Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History).

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission. Learn more.

Sources

- Judith Amador Tello. 2014. “Preservará el INAH la obra de Aurelio Escobar, fotógrafo de la Revolución.” Proceso, 14 Jan 2014.

- Arturo Guevara Escobar. 2008. “El Estudio Fotográfico H. J. Gutiérrez, un negocio familiar.” Blog post dated 24 Nov 2008, updated 4 Jan 2009.

- Arturo Guevara Escobar. 2011. “H. J. Gutiérrez.”

- El Tiempo Ilustrado: 26 April 1908, 8-11; 16 April 1911; 23 April 1911; 9 June 1912.

Comments, corrections and additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.