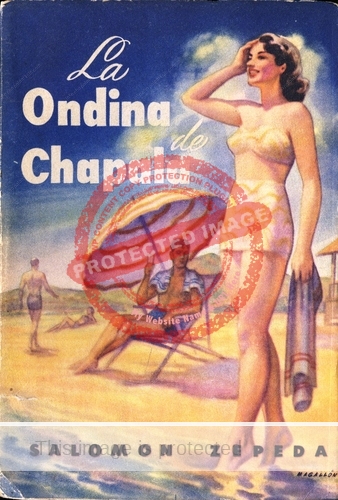

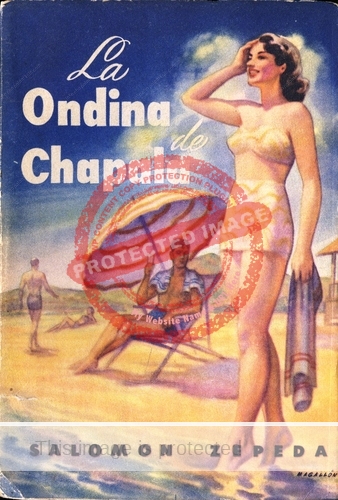

La Ondina de Chapala (“The Water Nymph of Chapala”) is a 149-page Spanish-language novel, set in the 1940s, by Salomón Zepeda. It was published in Mexico City by Imprenta Ruíz in 1951. Very little is known about the author.

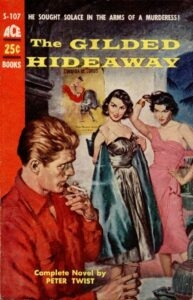

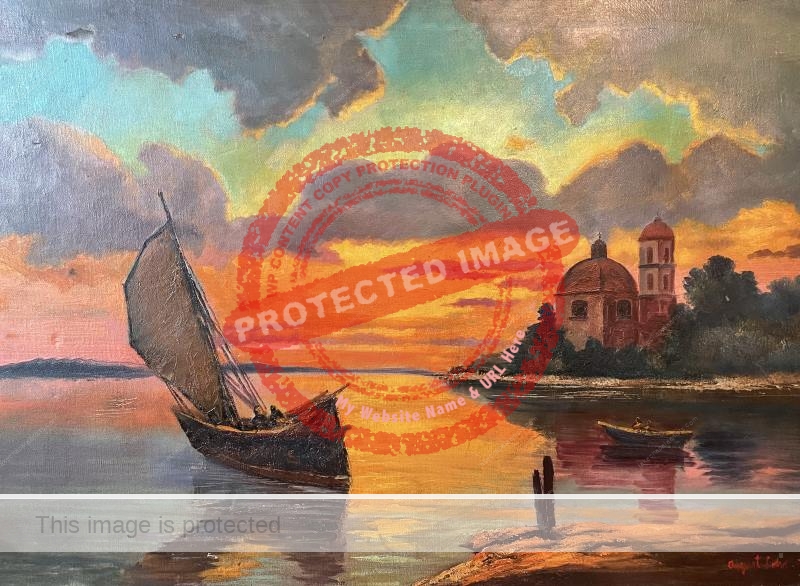

Until I had the chance to read this novel, I had always assumed—based on the cover art—that it was a pocket romance of relatively limited artistic merit. I was wrong. La Ondina de Chapala is a skillfully-constructed and well-written story which, while it has romance as a central theme, reflects on such timeless considerations in relationships as trust, fidelity, communication, sacrifice and betrayal.

The author was clearly a very well-educated individual, as evidenced by the many literary and artistic references in this book to the likes of Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer, Rousseau, Gauguin, Edgar Allen Poe, Rembrandt, Shakespeare and Arnold Böcklin, as well as to a number of Hindi poets.

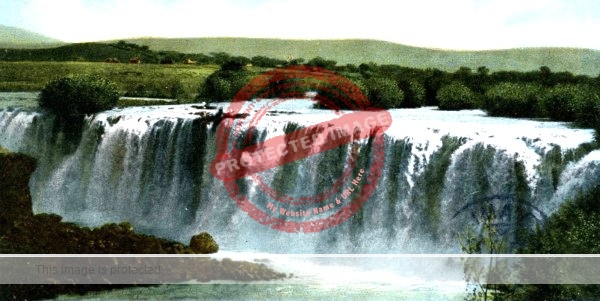

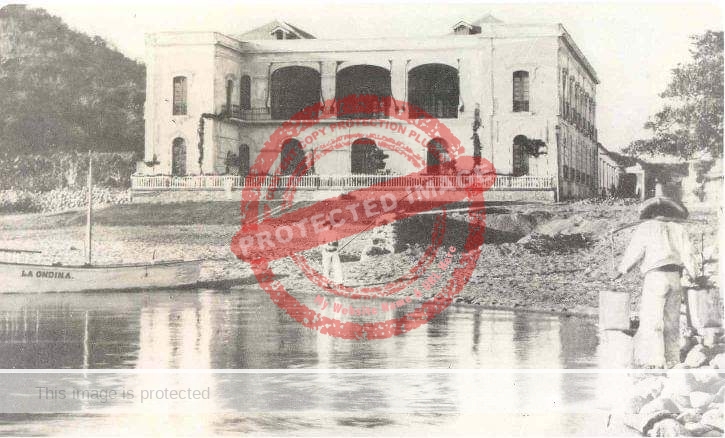

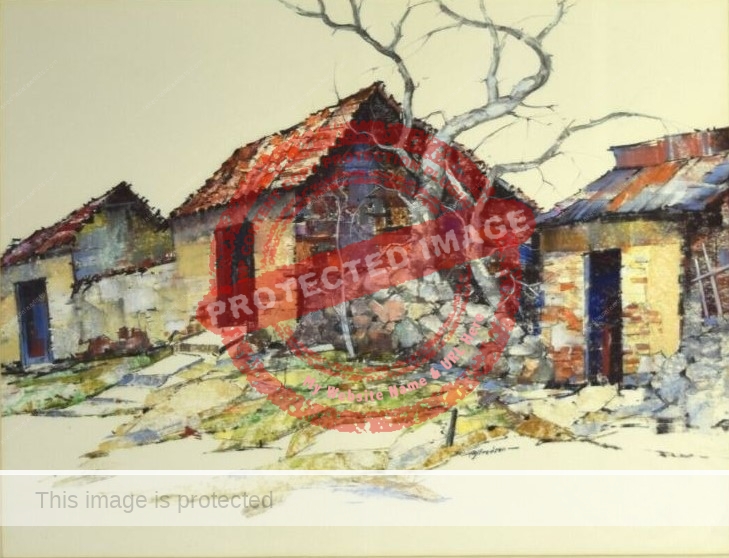

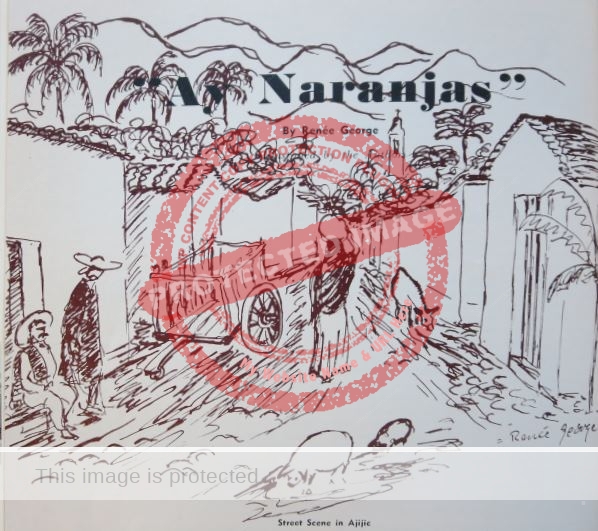

Charles Betts Waite. ca. 1900. Hotel Arzapalo. – By coincidence, “La Ondina” is the name of the boat in the foreground of this very early image of the Hotel Arzapalo in Chapala.

The title turns out to be particularly apt. An Ondine (also spelled Undine) is a mythological water-spirit or water-nymph that can obtain a human soul when she falls in a love with a man. However, the man is doomed to die if he is unfaithful to her.

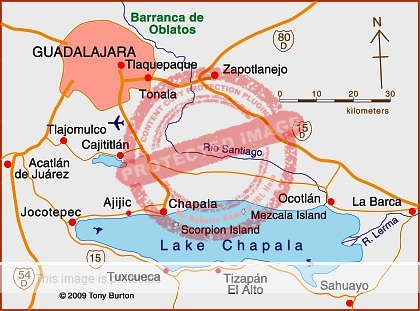

The protagonist in Zepeda’s novel is 27-year-old Erasmo Sada, a tall, muscular, college-educated author who has borrowed a car from a friend to drive out from Mexico City (where he is a newspaper editor) to Lake Chapala for a respite from his job and the city.

Erasmo took a room at the “Hotel de Oriente” and planned to work on his first novel, “Marfil de Luna.”

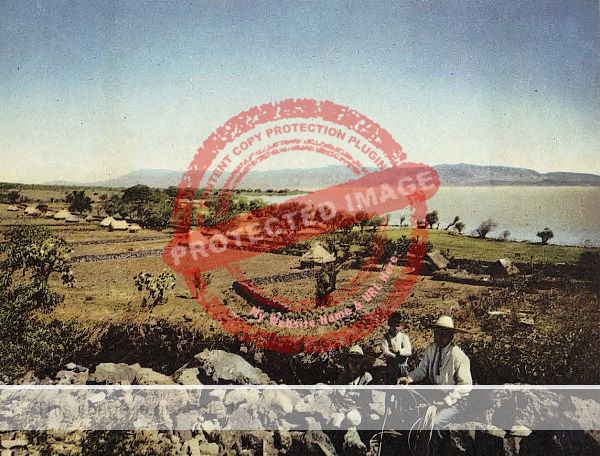

— “The resort was overflowing with Yanqui tourists of both sexes…. Towards the top of a hill, one could see the country houses, the chalets, the castles, the rustic cabins, the recreational villas and the palatial residences of the nouveaux riches, summering all year round…. Erasmo was content in that tourist emporium of yesteryear, where the rancid aristocracy of the age of General Porfirio Díaz whiled away their prolonged leisure time.”

Like all good authors, Erasmo always has his notebook to hand to record random thoughts, feelings, impressions and ideas.

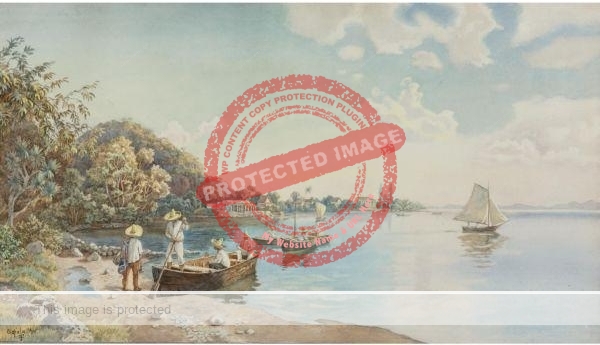

The morning after his arrival, he is relaxing in a deckchair on the beach amidst the multi-colored sunshades and watching the world go by, when a group of four girls arrives. They stake a place on the beach and then race into the water to swim. He cannot help but overhear their shouts as they cavort in the water and learns their names: Vera, Susana, Angelina and Adelaida.

He is instantly smitten with Adelaida who seems somehow different and more self-confident than the others. He sneaks glimpses of the stunning and shapely dark-haired girl until, at one point, she not only notices him but calmly returns his gaze.

After the girls dry off, change and leave the beach, Erasmo enjoys a lunch of whitefish at the Beer Garden and makes a journal entry—equal parts lust and curiosity—about “the Ondine of Chapala who had swum in the lake.”

The following morning, the girls are back; Erasmo watches Adelaida but does not approach her. That evening, when he goes for dinner to “Salon Chapala,” he finds that Adelaida is already there, drinking and dancing with friends, one of whom, an older-looking man, has a proprietorial air about him. After they’ve left, the bartender explains to Erasmo that the man is a Guadalajara lawyer and is Adelaida’s husband. The couple regularly visit his family’s villa in Chapala and are friends of the local mayor (presidente municipal).

In the course of the novel, as Erasmo ponders the meaning of what he feels and how he should act, his inner musings often veer off into topics that are quintessentially Mexican. For example, after sitting in a rocky field looking out over the lake, he suddenly realizes that he is uncomfortably close to a group of rattlesnakes making love. They trigger thoughts of the serpent cult in ancient Mexico, of Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent), and of the founding of Mexico City. As his mind wanders to the conflict between snakes and eagles, good versus bad, he recalls the archaeological evidence related to snakes and mythology elsewhere in the world, before snapping back to Lake Chapala as the weather worsens and a culebra (“water snake” – the local word for a waterspout) forms over the lake.

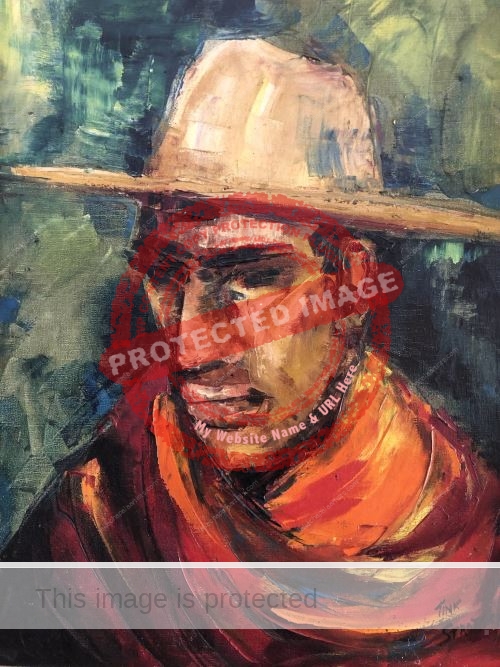

Cover art by “Magallón”

Safely back in his hotel, he watches the rain from his balcony. When the storm has subsided, the fresh earthy smell emanating from the ground prompts Erasmo to take a nighttime stroll through the village. He sees someone headed in his direction. The vaguely-defined distant shape gradually becomes more feminine and as the woman draws closer he recognizes Adelaida.

In the conversation that ensues, Adelaida makes it clear that she is fully prepared to accompany him back to his hotel room, but only on condition that he asks no questions and promises to have no further contact with her thereafter.

Erasmo can’t quite believe what is happening but agrees. They have a passionate one-night stand in his hotel room. Before she leaves in the early morning, she shares some of her life story with him to explain why she was wandering the streets at night… Long story short, she had barely left university when she married a much older man, Conrado Rubiera, who turned out to be an impotent alcoholic. Her husband became abusive and on one occasion attacked her with a knife. When Adelaida asked for a divorce, Conrado threatened to kill her.

In an effort to reconcile their differences they were spending several weeks in Chapala at his parents’ villa, Villa Solariega (“Ancestral Home”). However, their first attempt in months to make love ended in abject failure. Conrado had called her a whore and thrown her out; frustrated in more ways than one, she had stormed off and was wandering the streets in anguish prior to meeting Erasmo.

As Adelaida is about to leave the hotel, Erasmo suggests she leave her husband once and for all and that they drive away together back to Mexico City. She refuses, reminds him of his promise, and walks back to Villa Solariega.

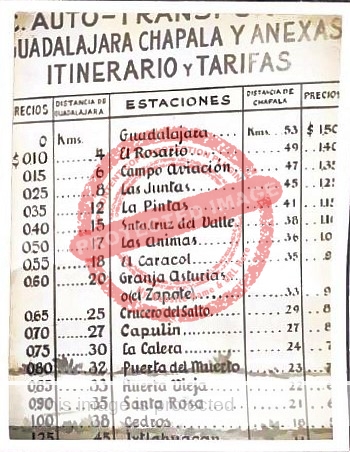

Erasmo, as he tries to make sense of events, ponders the “fragility of human destiny” and begins to reread his journal entries for the trip. The first entry, dated 15 May 1943, reflects on his feelings when he stopped at the viewpoint known as Mil Cumbres to look out over the forest towards the distant mountains.

“My life is a dream in pursuit of your footprint …”

Snapping back to the present, Erasmo composes a lengthy poem to Adelaida in which he expresses his eternal love. He fantasizes about what he calls the “Lake of Love,” which “will tell your heart of my insane anxiety until once again, in a distant world, we love each other in Eternity.”

On her way home, Adelaida’s interior monologue revolves around her feelings of guilt and remorse. She decides that she will ignore her husband’s threats and seek a divorce. However, when she arrives home, she discovers her husband dead in bed, pistol in hand. She screams for help and moves the pistol to the nightstand. After the local judge arrives, reports are filled out and Adelaida is placed in temporary custody at the house of the mayor, Ramiro Requena, while further investigations are carried out.

Adelaida’s fingerprints on the pistol, her ready admission of having had a serious argument with her husband only hours before his death, and her unexplained walk into the village at night, as well as the absence of any suicide note, all suggest she may have been implicated in her husband’s death.

Fortunately for Adelaida, her father-in-law arrives from Guadalajara. Confident that Adelaida must be completely innocent, he looks round the house and discovers a suicide note signed by his son. The note completely vindicates Adelaida who is released. Conrado’s body is taken by ambulance to Guadalajara for burial in the family crypt.

In the meantime, Erasmo Sada has arrived in Guadalajara, not knowing any of this, to stay overnight before driving back to Mexico City. At the downtown Hotel Metrópoli he is idly leafing through the newspapers lying on the table in the hotel lobby when he reads about the suicide and the funeral. His heart skips a beat. The article even includes Adelaida’s address.

For the next couple of days, unsure what he should do, he tries to distract himself by wandering the city streets to visit tourist sites such as the Museo del Estado, Los Colomos and Tlaquepaque. In the process, he muses about the origin and importance of Jalisco’s many contributions to Mexico such as mariachi music and tequila.

Eventually, he comes to a decision and enters a silver shop to purchase some earrings as a suitable gift for Adelaida. When he knocks on her door, there is no answer. Erasmo turns away dejected, wondering about love and destiny. Then, by chance, her maid arrives and explains that Adelaida is staying with her aunt Elisa in the colonial Agua Azul.

At the aunt’s house, Erasmo talks with Adelaida and they go for a walk. She loves the earrings but makes it clear that she is sticking to the “no more contact or explanation” agreement and is going to stay with a cousin in Chicago and start a new life. She agrees that Erasmo can see her off at the airport the following Saturday.

Erasmo paces the city streets trying to clear his head, desperate to work out how to convince her to change her mind and come to live with him in Mexico City. At the airport, Adelaida arrives alone, having made excuses as to why none of her friends or her aunt should see her off. She and Erasmo meet in the departure hall and start chatting. They hug and share a passionate kiss.

And… will she go to Chicago or will she marry Erasmo?…

Apology:

Sorry, but if you want to know the ending, you’ll either have to find and read a copy of this interesting book or email me a link to a rating, comment or review you have made on Goodreads, Amazon or elsewhere of any of my books.

Copies of La Ondina de Chapala are held in several libraries in Mexico City and the U.S., including the University of California Los Angeles and Southern Illinois University. Depending where you live, they may be available via inter-library loan.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

The work marked a milestone in the “genre of long-form compositions for wind ensemble” and has been recorded dozens of times since.

The work marked a milestone in the “genre of long-form compositions for wind ensemble” and has been recorded dozens of times since.

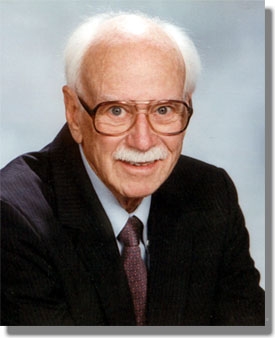

Louis Henry Charbonneau, Jr. was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 20 January 1924 and died in Lomita, California, on 11 May 2017. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at the University of Detroit.

Louis Henry Charbonneau, Jr. was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 20 January 1924 and died in Lomita, California, on 11 May 2017. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at the University of Detroit.

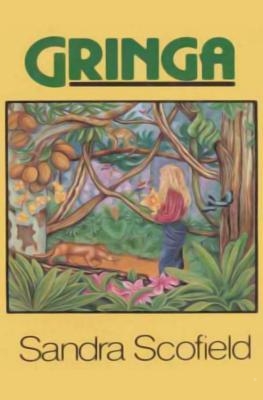

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.

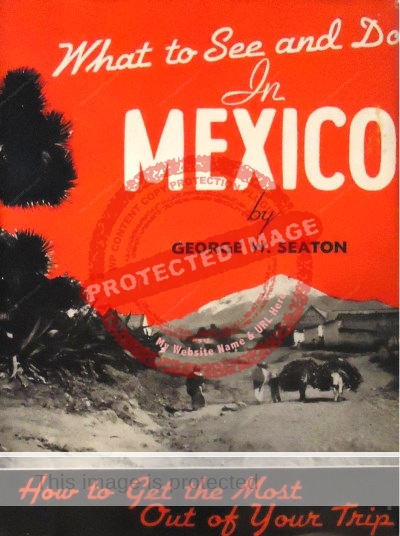

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”