Jakob Granat (1871-1945) was a Jewish merchant and businessman born on 18 October 1871 in Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine) in what was then part of the Austrian empire. He left Europe in July 1887 to seek his fortune in the U.S., where he was known as Jacob Granat. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in New York City on 11 July 1900, having worked as a salesman in New York, Chicago and San Antonio, Texas.

According to most sources, Granat moved to Mexico (where he was known as Jacobo Granat) in 1900, working first in Veracruz with an uncle, who had moved there in 1885, before striking out on his own in Mexico City two years later. However, many details of the popularly-repeated version do not match the available documentary evidence from Granat’s passport applications and known travel movements.

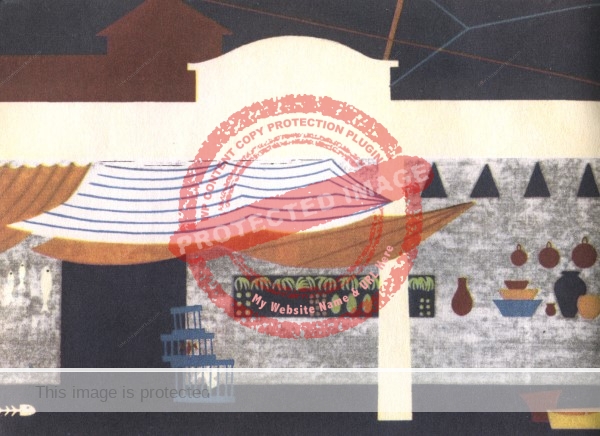

During his lengthy stay in Mexico, Granat established various businesses, including a leather and curios shop (selling “trunks, saddles, traveling bags and cases of all descriptions”), a printing company and a small chain of cinemas. Granat was a nephew of Jacob Kalb, who owned the Iturbide Curio Store, which also published postcards, in Mexico City.

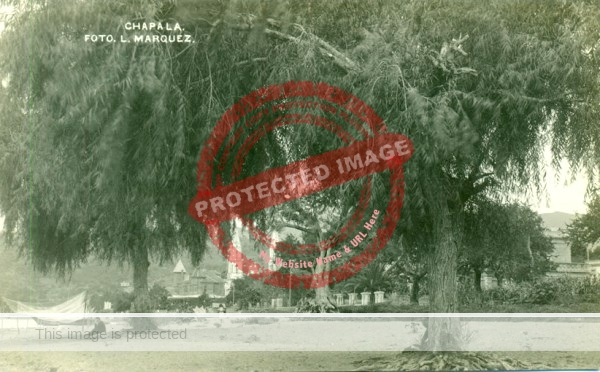

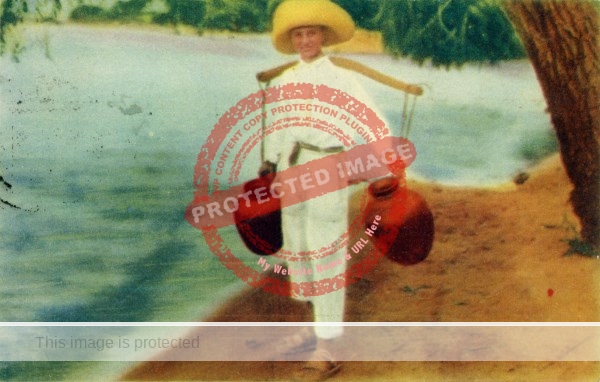

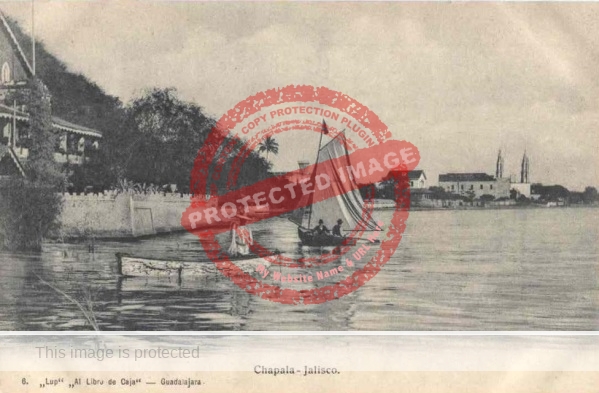

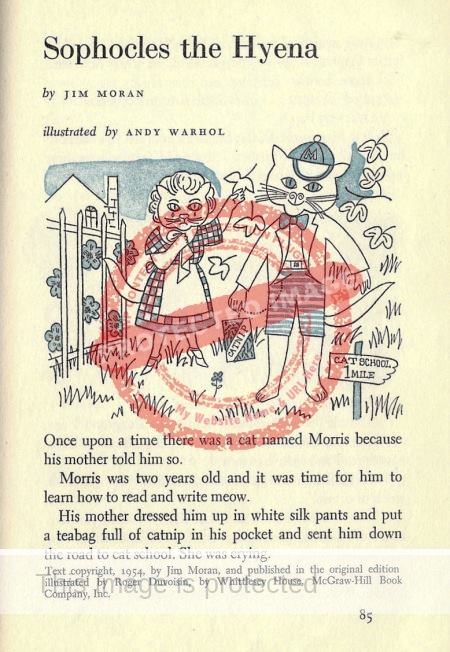

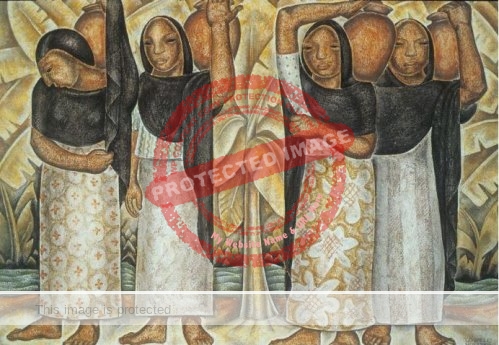

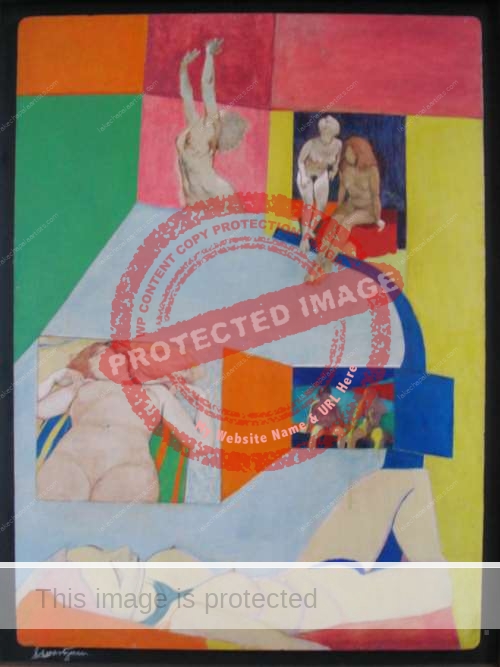

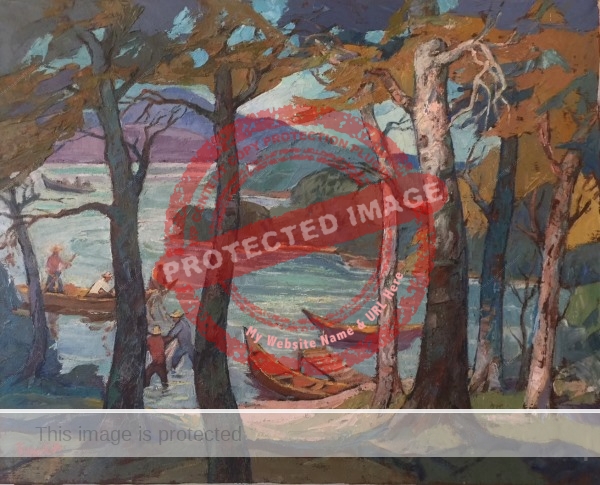

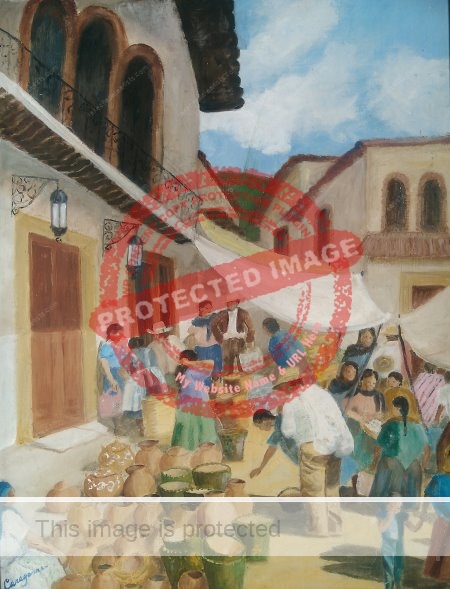

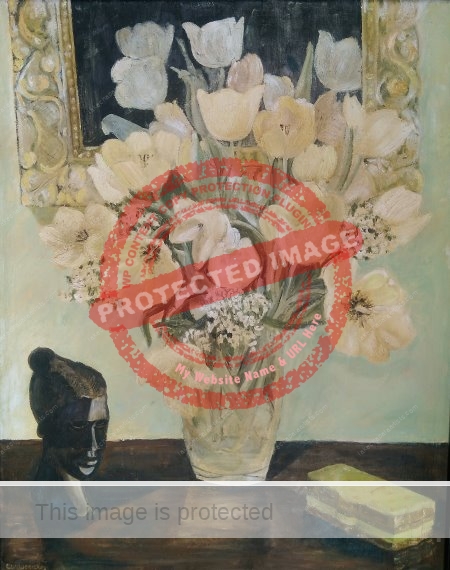

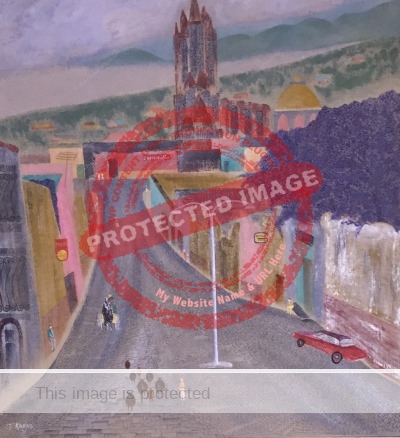

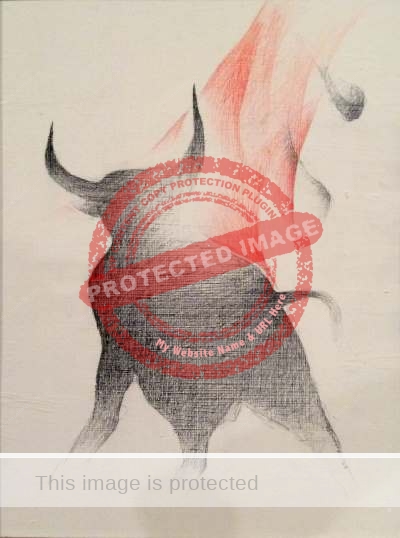

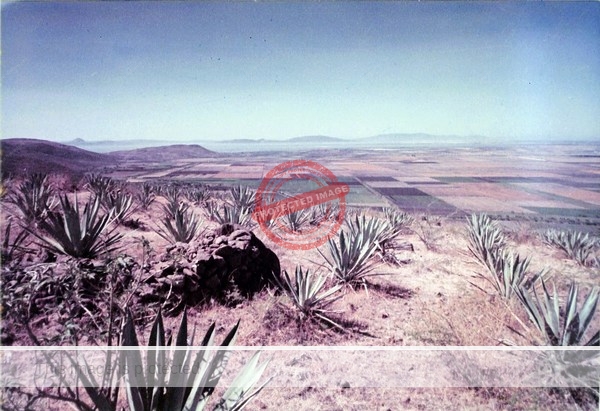

In about 1901, Granat began publishing postcards showing people, views and scenes from all over Mexico. Granat is believed to have published around 300 postcards, including this one of the buildings along the waterfront in Chapala. The most prominent buildings are the Arzapalo Hotel (opened in 1898) with its bathing huts (on the left), the turreted Villa Ana Victoria owned by the Collignon family (in the center) and the San Francisco parish church with its twin towers.

Winfield Scott. Lago de Chapala, c. 1905. Image colorized and published as postcard by J. Granat.

Aside: This iconic image of Chapala’s waterfront appears on the cover of If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants (2020), also available in Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes (2022).

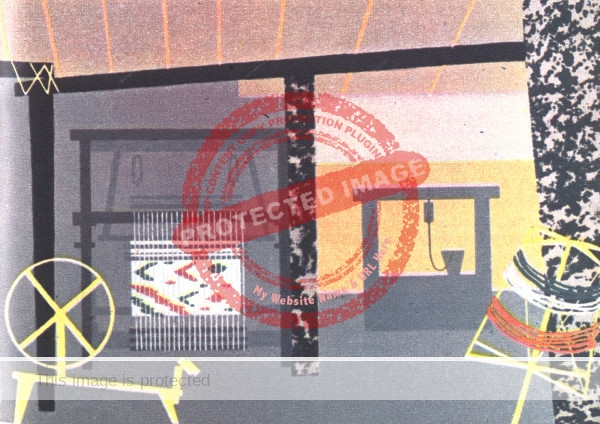

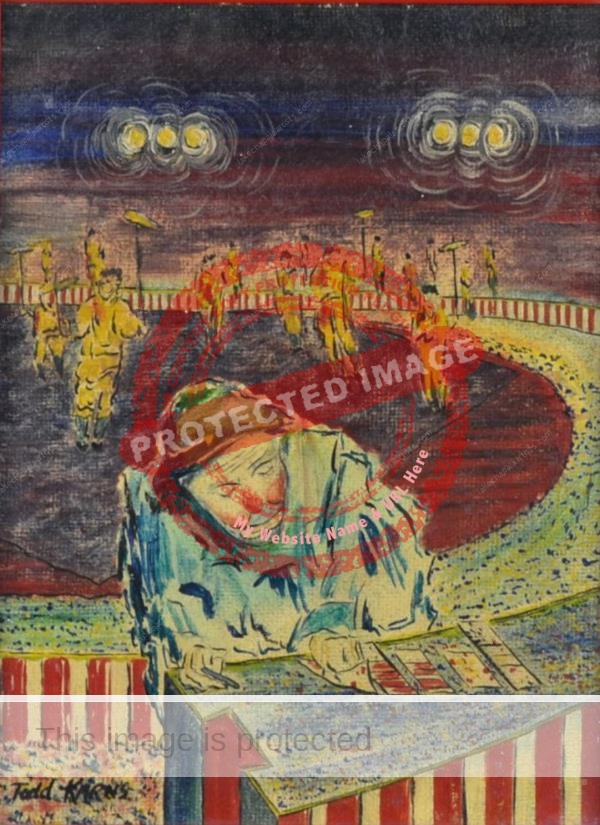

Granat is best remembered today for opening Mexico City’s first public cinema—El Salón Rojo—in 1906 by elegantly remodeling the interior of the downtown eighteenth century building known as Casa de Borda. The renovations included the installation of Mexico’s first electric escalator. El Salón Rojo quickly became the most famous of Mexico City’s early movie houses (of which there were eleven by November 1910) and the one favored by all the high society families, including those close to President Porfirio Díaz. El Salón Rojo eventually had three screening rooms and added a dance hall in 1921, as well as other public spaces. Located in the heart of the city, it was also in great demand for public and political meetings.

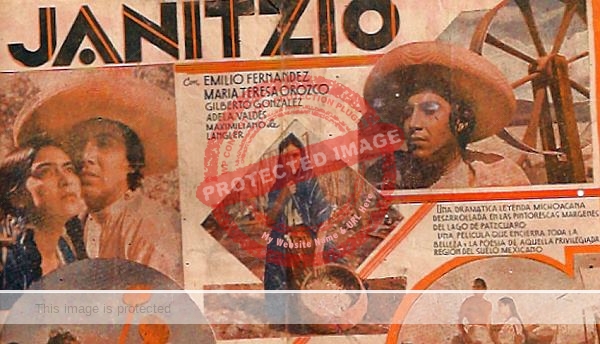

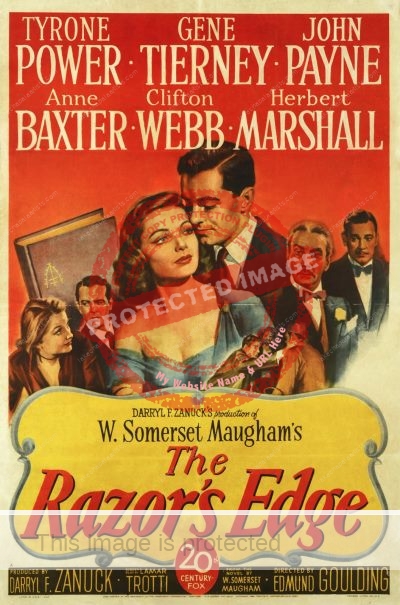

To help publicize the silent films being shown, which starred both Mexican and foreign actors, Granat published a series of small movie lobby cards, similar to postcards, sold in the theater lobby.

In 1912, when Francisco I. Madero was Mexico’s President, Granat was one of the prime movers behind, and first president of, a permanent Jewish charitable community in Mexico named Alianza Beneficencia Monte Sinaí. Four years later, the Jewish community was given permission by Venustiano Carranza in 1916 to establish a cemetery for the “Colonia Israelita de México” in Tacuba. The new cemetery came too late for Granat’s older brother, David Granat, who died of heart failure in Mexico City in March 1914 and was interred in the city’s French cemetery.

During the Mexican Revolution, Jakob Granat claimed on repeated passport applications to have returned to the U.S. every year since 1905 for between two and six months, though these claims may have been made only to prevent him losing his right to a U.S. passport.

According to documents he signed when registering his presence in Mexico with the U.S. Consulate-General in Mexico City in 1917, at that time he owned five cinemas in the city. The same documents also mention his leather and curios shop, stating that he manufactured “American trunks.” In a supporting affidavit, Granat swears he had “temporarily resided” in Mexico City since 1905:

“I am manufacturing and importing American trunks, bags and suit cases, including all the materials, such as nails, wood trimmings, locks, etc., from the United States. Also, I am importing American films, showing them exclusively in my five theaters, and in preference to European films. I purchase my trunk materials from R. Newman Hardware Co., P. Stiger Tunk Co., and M. Goulds Son & co., all of Newark, N.J. I buy films from almost every American manufacturer. Since residing abroad, “Every year, I have spent from two to six months in the United States.”

Life in Mexico City was apparently becoming quite difficult and Granat stated that his intention to return permanently to the U.S. “as soon as conditions permit me, as I intend to sell out my interests here.”

Curiously, among these documents is a declaration that Granat was not married. This does not match his status as recorded on earlier passenger manifests or, indeed, explain the U.S. passport application he makes in Mexico City a few years later, in 1921, which specifically includes his wife, Alma Nebenzahl.

The 1921 passport application lists his occupation as “Moving picture Manager on behalf of the Orozco Circuit, handling American films for the Republic of Mexico.” According to the paperwork, Granat (then 50 years of age, 5’4″ tall with brown hair and blue eyes) planned to travel to Europe. He named England, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Holland, Switzerland and Belgium as intended destinations; a later amendment (dated March 1922) added Poland.

Granat’s personal reputation had been severely tarnished after July 1920 as a result of allegations made about his possible relationship with a young girl, an employeed in El Salon Rojo, who had taken her own life.

At about this point, Granat found a willing purchaser for his cinemas in the form of William O. Jenkins, an unscrupulous American businessman and property speculator then living in Mexico City. Jenkins, the subject of a recent biography by Andrew Paxman, had already made millions and went on to enjoy a virtual monopoly over Mexico’s booming movie business during the 1930s and 1940s. Later, following the death of his wife, Jenkins turned philanthropist and devoted his considerable wealth and energy to create a charitable foundation which helped establish the Universidad de las Américas.

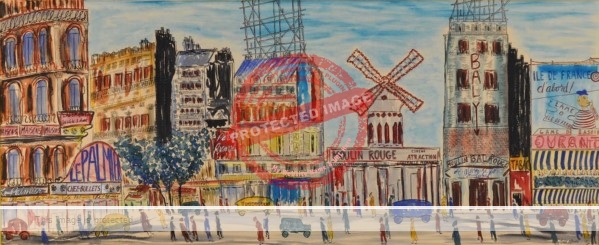

Claims that Granat left Mexico in about 1920 and—perhaps at the insistence of his wife—returned to Europe where they were still living when the second world war erupted in 1939 appear to be overly simplistic. For example, in 1927, Granat, traveling alone, re-entered the U.S. on 23 February, having traveled from Hamburg on board the SS Albert Ballin. Three years later, on 21 August 1930, Granat (without his wife) again entered the U.S. from Mexico. In 1936, Granat, 64, retired (and now claiming to hold Mexican citizenship), arrived at the port of New York again on 28 Jan 1936, coming from Le Havre, France, on board the Ile de France, and in transit, presumably to Mexico. Yet again, he appears to be traveling alone. These trips were presumably to see his family members (including his sister-in-law and her children) who were still living in Mexico City.

When the second world war did begin, Granat (and presumably his wife) did find themselves trapped in Europe. Despite the claim made in Mexican sources that Granat was killed in the gas chambers at Auschwitz in 1943, the Holocaust Survivors and Victims Database shows that his death came not at Auschwitz but at the equally infamous Bergen-Belsen concentration camp two years later, on 27 January 1945. His wife’s name does not appear in the database, though it is possible that she died in Auschwitz in 1943, since only fragmentary records exist of the thousands who lost their lives there.

Note: This is an expanded version of a summary post first published 22 July 2018.

My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources:

- Miroslava Callejas. 2016. El primer cine capitalino y el primero con escaleras elétricas, El Universal, 24 October 2016.

- Alicia Gojman Goldberg. 2010. “Los inmigrantes judíos frente a la Revolución Mexicana”, presentation at the XIII Reunión de Historiadores De México, Estados Unidos y Canadá.

- Arturo Guevara Escobar. 2011. “Letra G. “Fotógrafos y productores de Postales.” Blog entry dated octubre 4, 2011.

- Holocaust Survivors and Victims Database. [8 July 2018]

- Gregory Leroy. 2017. “The adventurous and tragic life of Jacob Granat” Blog post on Early Latin American Photography.

- Valentina Serrano & Ricardo Pelz. 2015. “Serie Azul y Roja de Jacobo Granat.” Presentation, 8th. Mexican Congress on Postcards, Palacio Postal, Mexico City. 16-18 July 2015.

- Kathryn A. Sloan. 2017. Death in the City: Suicide and the Social Imaginary in Modern Mexico. Univ of California Press, 170-172.

- Andrew Paxman. 2017. Jenkins of Mexico: How a Southern Farm Boy Became a Mexican Magnate. Oxford University Press.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.