The renowned Hollywood portraitist Richard Kitchin lived in San Antonio Tlayacapan in the 1970s.

Richard (‘Dick’) Harwood Dodwell Kitchin was born on 15 Jan 1913 in Oxted, Surrey, England, to Vernon Parry Kitchin, a teacher and amateur archaeologist, and his wife, Phyllis Annie Dodwell Kitchin. Richard’s inspiration to become an artist undoubtedly originated from watching his parents enjoy their shared hobby for painting.

When Richard was 6 years of age, the family moved to Château-d’Oex, Vaud, Switzerland. At age 13, Richard was sent back to the UK to join his older brother, Michael, at Stowe School in Buckingham. Michael had started at Stowe shortly after it opened in 1923.

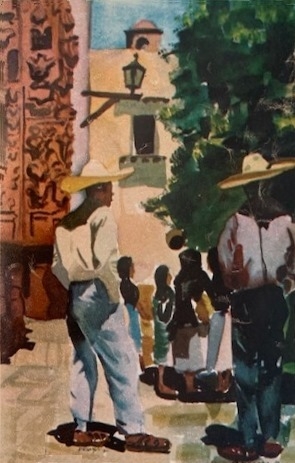

At Stowe, Richard’s classmates included James ‘Peter’ Lilley (1913-1980) and Anthony Stansfeld (1913-1998). Lilley and Stasfeld later collaborated to write several books, including two detective novels (using the pen name of ‘Bruce Buckingham’) and several travel books (taking on the nom de plume of ‘Dane Chandos’ after the death of Lilley’s first writing partner, Nigel Stansbury Millett). The Lilley-Millett duo had penned Village in the Sun and House in the Sun, and Lilley shared his beautiful real-life home in San Antonio Tlayacapan, the basis for those early Dane Chandos works, with Kitchin in the 1970s.

The earliest significant mention of Kitchin in The Stoic (the Stowe School magazine) comes from 1929, in the notes of The Arts Club: “R H D Kitchin’s water-colour sketches are full of promise.” Kitchin was awarded his School Certificate that year, and (along with Stansfeld) was also a member of the school’s Modern Language Society. The following year, Kitchin was awarded the Headmaster’s Art Prize in a show judged by then up-and-coming (later famous) British artist Rex Whistler.

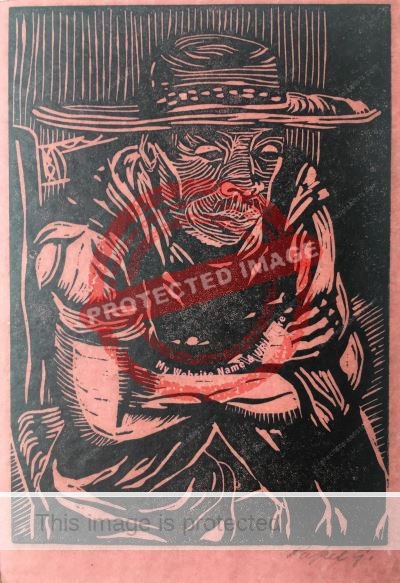

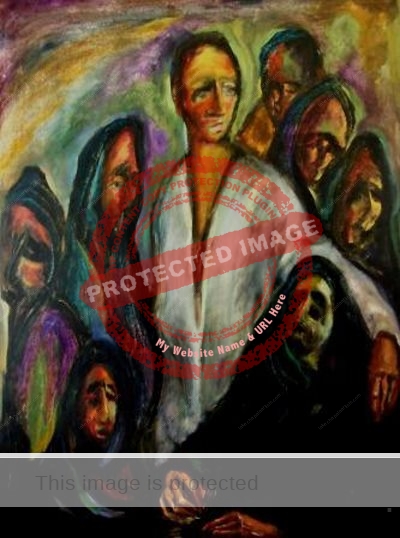

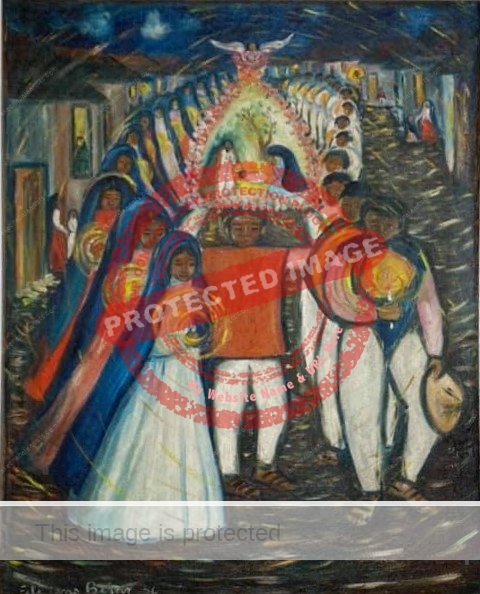

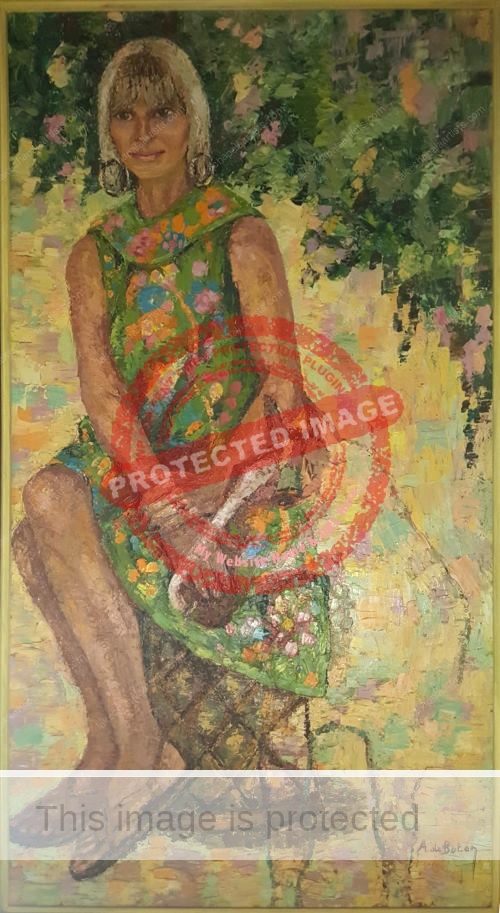

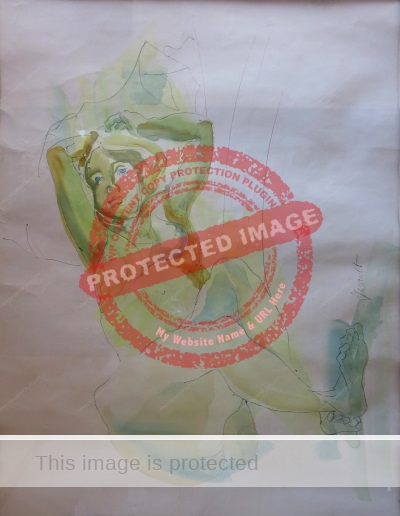

Richard Kitchin. 1937 Self portrait. Credit: Instituto Cultural Cabañas.

Kitchin left Stowe in summer 1930 to enter the Slade School of Art in London, and immediately won second prize in the Slade’s Summer Sketching Competition. After completing his studies at the Slade School in 1932, Kitchin continued his art education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence (1932-1934), the Ecole d’Art in Paris (1934-1938), and via private classes with ‘Prof. Pashaud’ (sic) in Switzerland (1936-1938). (This refers to John Paschoud (1901-1998).

This self portrait dated 1937 is in the permanent collection of the Instituto Cultural Cabañas in Guadalajara.

By 1939 and the start of the second world war, Richard was based in London, sharing a house with playwright Martyn Coleman Whiteman. In 1940 they left the UK and traveled to Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Far East, from where they crossed the Pacific aboard the SS Poelau Bras, arriving in California on Christmas Eve.

Kitchin and Whiteman both registered for the US military in July 1941. A few months afterwards, they are recorded as entering the US from Tijuana, Mexico, and declaring their intention to reside permanently in the US. Two years later, both men signed and submitted paperwork for permanent residency, stating that their last permanent address outside the US had been in Yugoslavia.

In the 1940s, Kitchin quickly established himself as a portrait painter in California. For example, the Los Angeles Times reported in December 1943 that Mrs J Howard Hales had held a cocktail party for friends in her Beverly Hills apartment to show off Kitchin’s portrait of her.

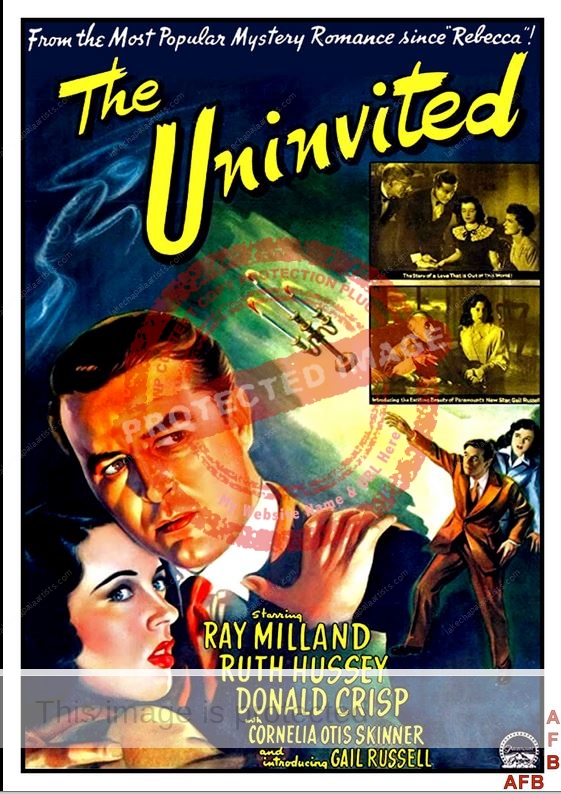

Movie makers in the 1940s also sought Kitchin’s expertise. For example, the makers of The Uninvited, released in 1944, commissioned Kitchin to paint “two huge paintings of Mary Meredith.” According to a blog post by film buff Remy Dean:

… the two huge paintings of Mary Meredith deserve a mention. One takes up a wall of Stella’s bedroom at her grandfather’s house. The other is equally huge and dominates Miss Holloway’s office at The Mary Meredith Retreat—a kind of polite asylum for overwrought women. It’s all we see of this supposedly perfect woman, painted in the style of Thomas Gainsborough by the hugely talented Richard Kitchin.”

Although uncredited, the sitter for the portraits was Elizabeth Russell who subsequently played bit parts in several horror films. Interviewed for the Detroit Evening Times, Russell explained that her “chief joy” of sitting for the portraits “was that it called for her to spend seven weeks in the studio of Richard Kitchin…. She’s thrilled that one of the paintings recently took first place at a Denver art show.” (The details of that show, believed to have been held in the “State Museum,” remain elusive.)

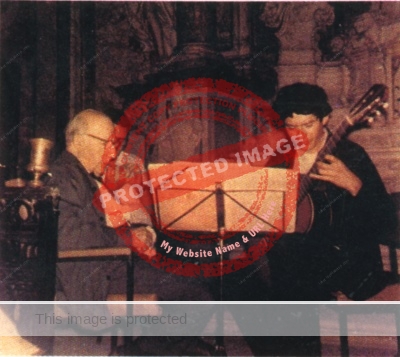

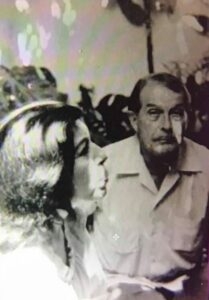

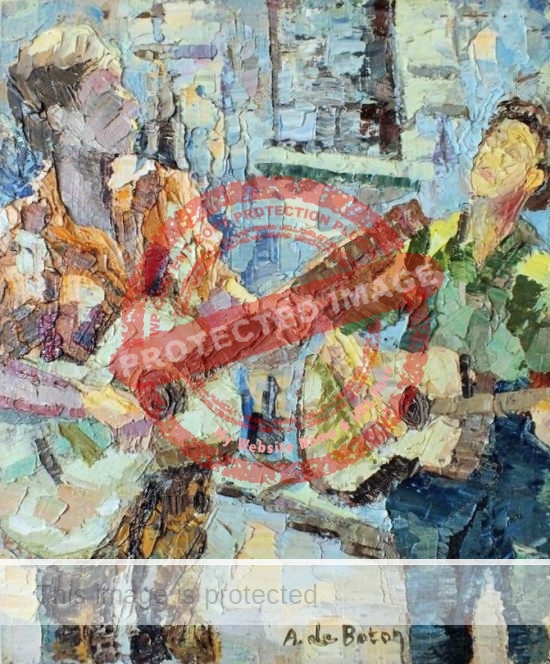

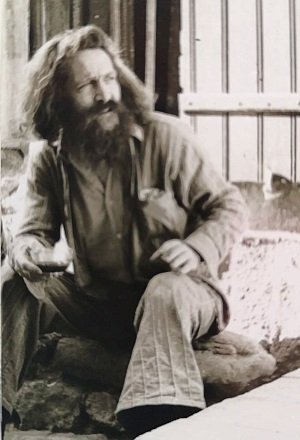

Richard Kitchin at work. Photograph in possession of Moreen Chater; reproduced with permission.

A portrait by Kitchin also featured prominently in another film, the 20th Century Fox crime drama The Dark Corner (1946), starring Lucille Ball, Clifton Webb, William Bendix and Mark Stevens. Clifton Webb played a suave art connoisseur named Hardy Cathcart, and Kitchin was commissioned to paint “an ‘old master’ type oil portrait” of Hardy’s wife, Mari, played by Cathy Downs.

A contemporary account explained why this was one of the most challenging assignments the artist had ever had:

The 17th century-type portrait had to be true to the period, yet be a perfect likeness of dimpled brunette Cathy. The picture explains the possessive love of art connoisseur Webb who falls in love with his young bride because she is the living reincarnation of the portrait.”

In October 1945, the Los Angeles Times remarked that Kitchin’s portrait of Peggy Wood “was admired by Ronald Colman and wife, Admiral Ike Johnson and wife, Charley Brackett and Lester Donahue, among others.” That portrait is now in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

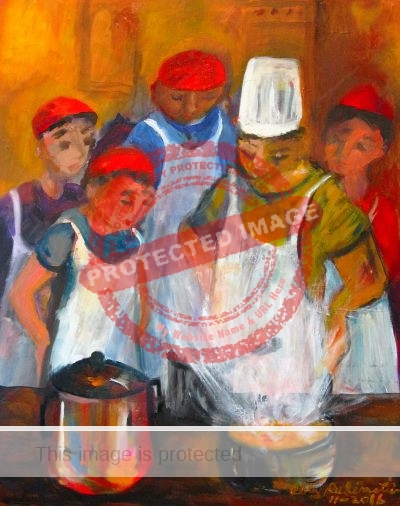

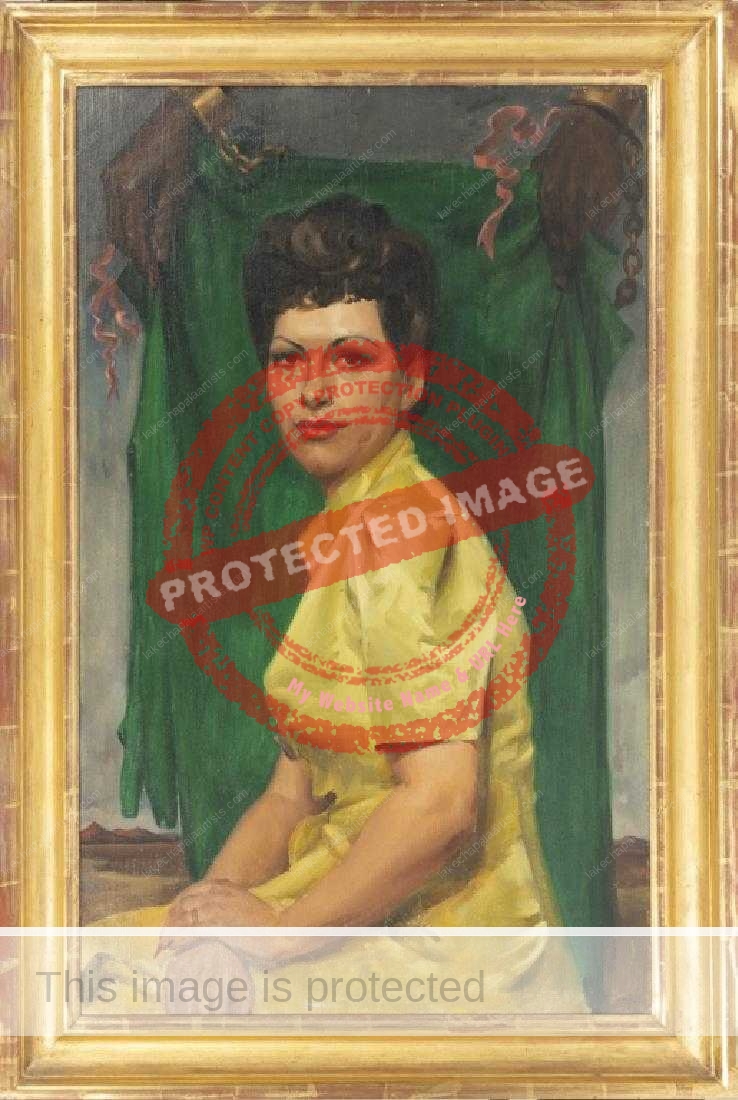

Richard Kitchin. Portrait of a lady. 1940s. Credit: Fine Estate, San Rafael, California.

Later that same month, the paper’s society columnist described how another Kitchin portrait had been less favorably received:

Mrs Smart was showing everyone her son Gillie’s new portrait, just completed by artist Richard Kitchin. After a number of “ohs” and “ahs” Nelson Eddy discovered that young Gillie was clutching an American Flag with only 11 stripes in it! Mr. Kitchin is being paged to DO something about this!”

Kitchin painted portraits of dozens of well-known theater personages, such as Ronald Colman (to whom he gave landscape painting classes), Ilka Chase, Ann Todd and Richard Barthelmess.

Richard Kitchin. 1942. “Dwight Ripley.” Courtesy of Douglas Crase.

Kitchin’s circle of friends in Hollywood included botanist-artists Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby. In his closely observed biography of the couple, Douglas Crase described Kitchin (whom he also knew) as “a set artist who painted the Surrealist portrait of Dwight that hung in Rupert’s bedroom.” That portrait was included in the show at Denver Art Museum mentioned previously. Crase shared with me that Kitchin’s portrait of Barneby met with less success—the subject didn’t like it and (sadly) destroyed it.

During his career as a thriving commercial portrait artist, Kitchin rarely exhibited his work. However, in addition to the Denver show, he did show a painting in 1945 in the Second National Competitive Exhibition of Glendale Art Association in California. A reviewer of the “excellent show of 79 paintings” chose Kitchin’s “Circus No. 6″ as their second favorite; the show’s jury awarded it third place.

Kitchin’s circle of friends in California also included the very talented British-American author Christopher Isherwood, who later based one of the characters in his novel Down There on a Visit (1962) on the portraitist.

At the end of the following year (1946) Kitchin made his first visit to Guadalajara, apparently at the request of US consul James E Henderson who commissioned a portrait of his wife, Elizabeth Mendell de Henderson. Kitchin was guest of honor at the unveiling cocktail party at the Hendersons’ home in Tlaquepaque, where the other guests included Jorge Álvarez del Castillo; Jack Bennet[t] and his wife, Sra Elitka de Bennet[t]; Ing Ricardo Lancaster Jones and wife, Luz Padilla de Lancaster Jones; Sr Peter Lilley; Ing Jorge Matute y esposa Esmeralda; Dr. Casimiro Ramirez Jaime; and Anthony T Williams, the UK vice consul in Guadalajara.

Kitchin’s Henderson portrait was displayed at a group show of “work by visitors to this region” at the Villa Montecarlo in Chapala in January 1947. Other noteworthy artists displaying work in this show included Linares (Ernesto Butterlin), ‘Charmin’ (Charmin Schlossman), Muriel Lytton Bernard, Charlotte Wax [?] and several unnamed Spanish artists. A selection of earthenware sculptures by Robert Houdek was also on show.

Kitchin revisited Guadalajara in October 1947, when he attended another social reception at the Hendersons’ home. On that occasion, the other guests included Jack Bennett and his wife, and UK vice consul Anthony T Williams and his wife, María Cameron de Williams.

English author Sybille Bedford, who had known Kitchin in Europe, met him again at Lake Chapala in 1946-1947. Kitchin is “Jack D___” in her fictional, Mexico-based travelogue A Visit to Don Otavio, where he is described as an old friend from Paris, who had studied with French cubist painter André Lhote in the spring of 1939, and was currently staying at the lake with Peter Saunders (Peter Lilley), while working on portraits of “the Provincial Governor’s wife and sisters, and their jewels.”

Movie companies in Hollywood continued to offer work to Kitchin. In 1947, for instance, the artist was commissioned by Paramount to paint a life-size oil painting of Ann Todd for its Hal Wallis production of So Evil, My Love.

Interviewed at about that time for The Honolulu Advertiser, Kitchin explained that he thought that the second world war had changed “the American face.” Whereas the old face, “like the British face… was showing the droopy-mustached, mild-eyed tremble-chinned symptoms of weakness”, the post-war face had “deeper-set eyes, stronger constructions of the jaw, larger noses and heavier muscles.” Kitchin backed up his assertion that “One war can change the faces of people more than 100 years of evolution,” by referring to movie star Tyrone Power: “Even though he was 32 when he put on a marine uniform, the war molded his face into a stronger cast, even to the bone structure. And as a result he is handsomer than ever.”

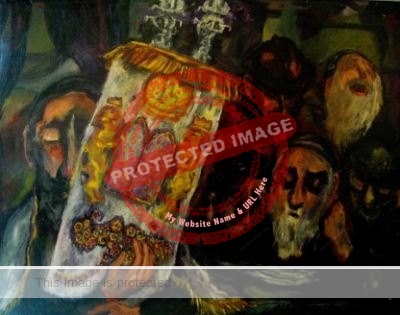

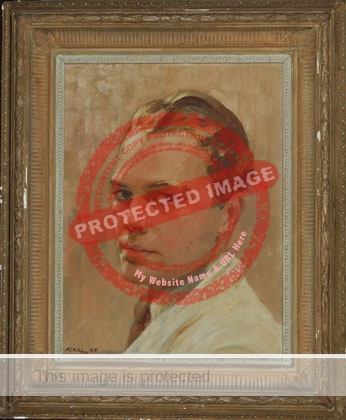

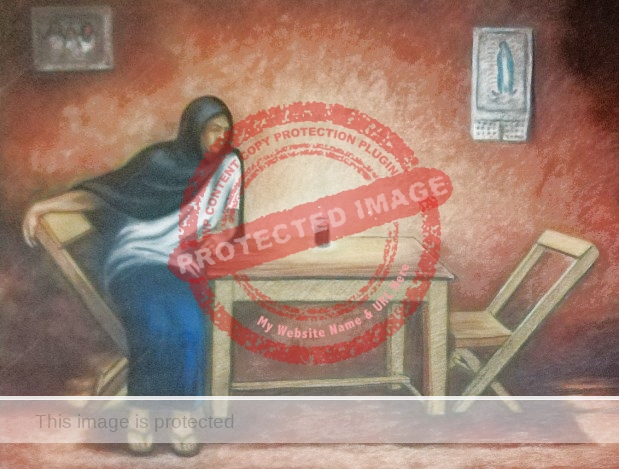

Richard Kitchin. Date unknown. Retrato de muchacha. Credit: Instituto Cultural Cabañas.

In about 1950, Kitchin returned to the UK to help his mother, who lived in Painswick, Gloucestershire, move home. During his time there, Kitchin did some restoring of old oil paintings, and taught an informal class of keen amateur painters some of the techniques involved (in exchange for the occasional bottle of gin).

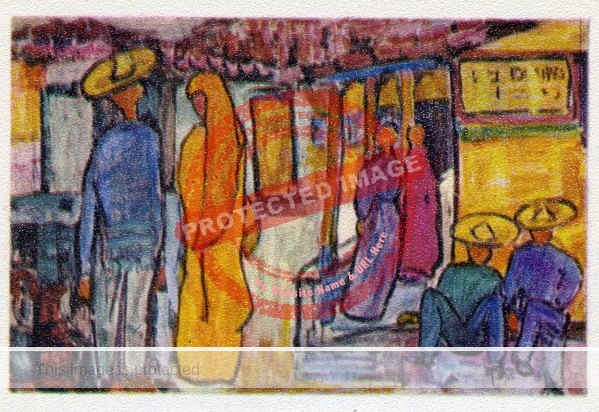

By the late 1950s, Kitchin was firmly back in Mexico, though frequently traveling overseas. During the next decade Kitchin completed dozens of portraits of high society figures in Mexico, up to and including Eva Sámano Bishop de López Mateos (the first wife of President Adolfo López Mateos), and Jalisco Governor Francisco Medina Ascencio and his wife, María de la Concepción Jiménez. In Guadalajara he had a close connection to the Country Club and painted many of its members and their families.

Precisely when Kitchin came to live with Peter Lilley in San Antonio Tlayacapan remains unclear (and it appears he continued to keep a home in Guadalajara) but he was certainly resident in the village by 1971. In October 1971 he held a “magnificent exhibition of paintings,” in two rooms of the Palacio Federal in Guadalajara. On display at the one-person show, which attracted a great number of visitors, were about 100 oil paintings, mainly portraits of persons well-known in Guadalajara society. In honor of the show, his long-time friend James E Henderson threw a huge party.

According to Manuel Morones, writing in El Informador at that time, Kitchin had previously painted at least six murals in Mexico City: five at the Club de Banqueros de Mexico and one at the University Club. If you can offer any more details about these murals, especially whether or not they still exist, please get in touch.

Kitchin’s mother, now well into her eighties, visited Mexico in late 1971 for several months to spend time with her son. Kitchin accompanied his mother back to the UK in April 1972, and spent several weeks in Europe later that year.

In May 1976, Kitchin held a solo show in Guadalajara’s Centro de Arte Moderno (Av. Mariano Otero 375) of works described as “magic realism,” though, according to a local critic, that eye-catching description was totally inaccurate! Again, if you have knowledge of (or a catalog from) this exhibit, please get in touch.

In July, Kitchin was one of five artists who arranged an exhibit and talk at Molduras Guadalajara del Sol in Plaza del Sol, Guadalajara.

Two months later, a selection of Kitchin’s portraits, in oil, pastel and charcoal, was included in a group show titled “Panorama del Arte en Jalisco”, held in three rooms of the DIF building in the small village of Teuchitlán, the closest village to the Guachimontones archaeological site. Other artists also exhibiting on that occasion, and with close links to Lake Chapala, included Sabina Foust, Gustel Foust and Ellis Credle Townsend.

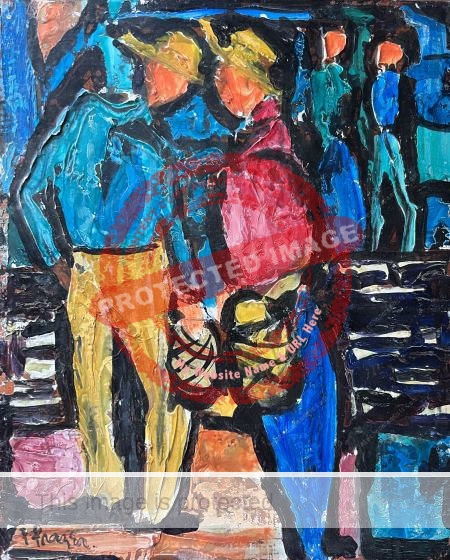

From 1979 to 1983 inclusive, Kitchin exhibited annually in “El Salón de Retrato,” a collective exhibit of portraits at the Galería Municipal in Guadalajara. The image accompanying the announcement of the 1980 show was a portrait by Kitchin of a child. Muralist Guillermo Chavez Vega was also exhibiting in that show.

Looking for an early Christmas gift, a bunch of hoodlums kidnapped Kitchin’s chauffeur (chofer) in December 1986 and demanded US$50,000 ransom. Three men were quickly arrested after the chofer managed to escape and seek help.

Portraits by Kitchin rarely come up at auction, presumably because they are still treasured by their subjects or heirs, though one exception, a portrait of a lady dating from the 1940s, was auctioned by Fine Estate in San Rafael, California, in 2018.

While living in San Antonio Tlayacapan, Kitchin completed portraits of many local residents, and local artist and cultural promoter María Victoria Corona Vega kindly asked local villagers, on my behalf, what they could recall about Richard Kitchin. Their most dramatic collective memory concerned how the strong feelings between two of Peter Lilley’s employees (Juan Espinoza from San Antonio, and Jorge from Ajijic) had led to a terrible tragedy, in which the two workers, who “could no longer bear working together for Don Pedro” killed each other in a personal confrontation. At Lilley’s request, Richard Kitchin subsequently painted a mural of the two men (together) on the living room wall.

Kitchin died in Guadalajara on 15 May 1991 at the age of 78, bequeathing much of his personal art collection to the Instituto Cultural Cabañas. The artworks include more than a dozen portraits—several related to Guadalajara and Lake Chapala—in addition to works by his parents, including some lovely realist watercolor landscapes by his father, Vernon Parry Kitchin, and a few more impressionist paintings by his mother, Phyllis Annie Kitchin (née Dodwell). Note that Phyllis’ paintings are mistakenly attributed in the Cabañas online catalog to “Philips A. Kitchin.”

[Aside: I was astounded to discover, very recently, that Vernon Parry Kitchin’s 1920 watercolor titled “Criccieth” was in the Cabañas’ permanent collection. By happenstance, Criccieth is the small seaside town in North Wales where I spent many a childhood vacation!]

When the cultural center Casa Uribe Valencia opened in Guadalajara in 1997, the opening exhibit featured numerous portraits by Kitchin, who had “lived in this city from 1957 to his death.” According to Alberto Uribe Valencia, Kitchin had painted portraits of the British Royal Family, Margaret Thatcher, and dozens of prominent residents of Guadalajara including Tomás Agnesi, Elena Martínez de Aldana Mijares, Taty Aldrete Cuesta, Ileana de Santiago de Barbosa, Margot Javelly de Brun, Susana Corcuera Verea, Carmen G de Corvera, Carmiña Rivero Schnaider de De la Peña, Gabriela de García Aceves, Ibela García Cuzin, Melin Fajardo de Godínez, Lucero Arroniz de Jarero, Betina Jarero Arroniz, Odette Berlie de Leal and Bertha Rabinovitz. He also painted many members of the Peralta family.

The influence of Kitchin lives on in Mexico through the work of artists such as Ricardo León, inspired and taught by Kitchin for a decade.

Acknowledgments

- My gratitude to Binky Chater for sharing with me her memories and the photograph of Richard Kitchin; to María Victoria Corona Vega for her research assistance; to author John Garner for alerting me to the Detroit Evening Times piece which mentions Richard Kitchin taking first prize in a Denver art show; to historian-genealogist Rodrigo Alonso López Portillo y Lancaster Jones for sharing with me his own extensive research relating to Kitchin, to author Doug Crase for sharing his knowledge of the artist, and to Louis Pachaud for identifying John Paschoud as the ‘Prof. Pashaud’ who gave classes to Kitchin.

Note and mea culpa

- This is an updated, corrected and expanded version of a post first published in July 2022. In the previous version I mistakenly spelled his surname “Kitchen” (as used in several newspaper sources).

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Sources

- Val ffrench Blake. 2011. Mainstay: A Twentieth Century Life. Bene Factum Publishing.

- Remy Dean. 2018. “Film Review THE UNINVITED (1944).” Blog post dated 15th October 2018.

- Douglas Crase. 2001. Both: a portrait in two parts. Pantheon Books.

- Gill Hedley. 2020. Arthur Jeffress: A Life in Art. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- El Informador: 27 Dec 1946, 7; 29 Dec 1946; 24 Jan 1947, 6; 26 Oct 1947, 11; 7 June 1960; 24 Oct 1971, 4-A; 25 Oct 1971, 11; 1 June 1977; 21 Jan 1979; 25 Feb 1980; 6 March 1980; 24 Jan 1981; 21 Jan 1982; 16 Feb 1983; 16 Dec 1986; 19 May 1991, 18-A; 15 Oct 1997, 51.

- Guadalajara Reporter: 15 May 1976, 11; 23 Sep 1978, 6.

- Los Angeles Times: 1 Dec 1943, 23; 13 May 1945, 26; 2 Oct 1945, 11; 23 Oct 1945, 17; 30 Jun 1946, 21, 22.

- Manuel Morones. 1971. “Galerías: Jalisco en la Cultura, A.C.”, El Informador, 19 Oct 1971.

- Harriett Parsons. 1944. “Keyhole Portraits,” Detroit Evening Times, 21 May 1944, 89.

- Shamokin News-Dispatch (Shamokin, Pennsylvania): 26 Jun 1946, 9.

- The Glamorgan Advertiser and Weekly News: 16 May 1947, 6.

- The Honolulu Advertiser: 2 Feb 1947, 44.

- The Stoic (Stowe School magazine): #16 (July 1928); #19 (July 1929), 247; #20 (December 1929), 4, 36; #21 (April 1930), 77; #22 (July 1930), 90; #23 (December 1930), 150.

This post was first published on 14 July 2022 and last updated on 1 July 2025.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.

After the death of her second husband, Caldwell had a brief marriage with William Stancell before marrying Canadian William Robert Prestie in 1978.

After the death of her second husband, Caldwell had a brief marriage with William Stancell before marrying Canadian William Robert Prestie in 1978.

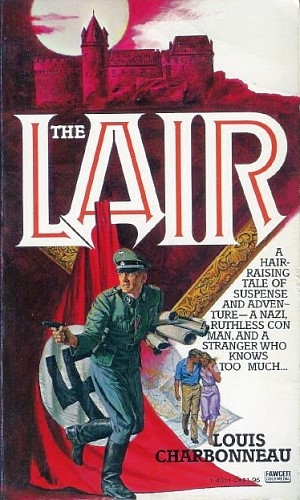

Louis Henry Charbonneau, Jr. was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 20 January 1924 and died in Lomita, California, on 11 May 2017. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at the University of Detroit.

Louis Henry Charbonneau, Jr. was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 20 January 1924 and died in Lomita, California, on 11 May 2017. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at the University of Detroit.