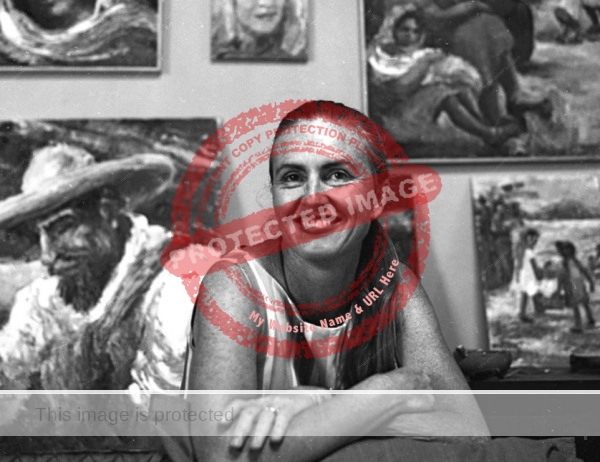

Roy Vincent MacNicol (1889-1970), “Paintbrush Ambassador of Goodwill”, had an extraordinary artistic career, even if his personal life was sometimes confrontational.

The American painter, designer, writer and lecturer had close ties to Chapala for many years: in 1954, he bought and remodeled the house in Chapala that had been rented in 1923 by English author D. H. Lawrence, and then, according to artist Everett Gee Jackson, by himself and Lowell Houser.

After MacNicol and his fourth wife Mary Blanche Starr bought the house, they divided their time between Chapala and New York, with occasional trips elsewhere, including Europe. Their New York home, from 1956 (possibly earlier) was at 100 Sullivan Street.

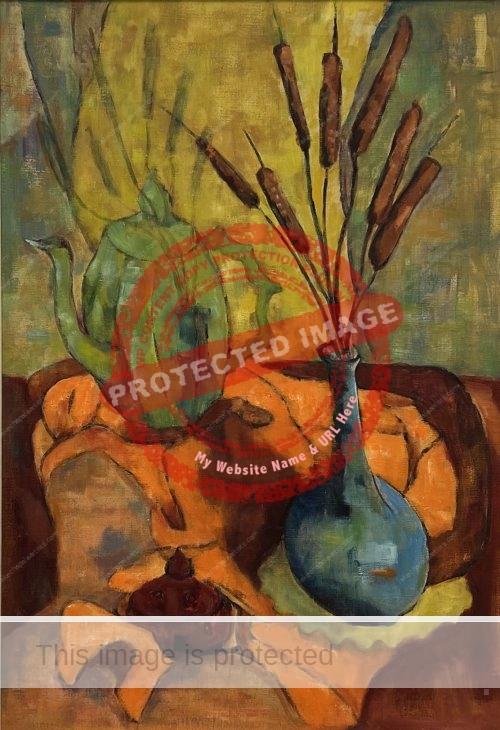

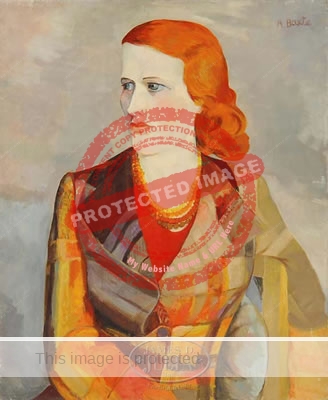

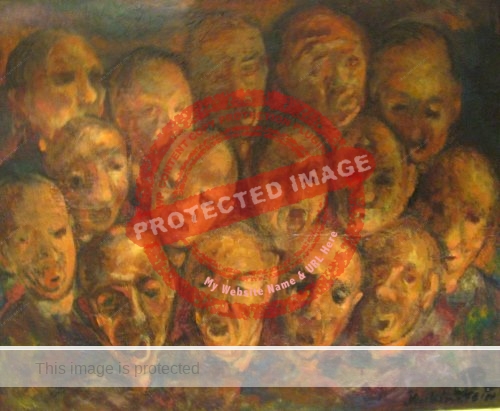

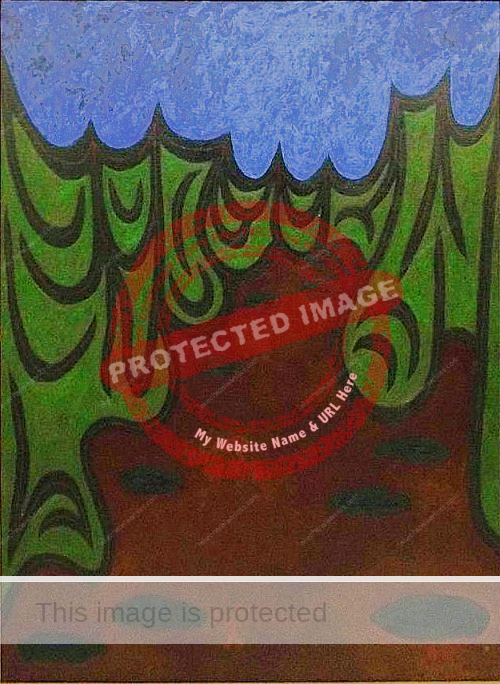

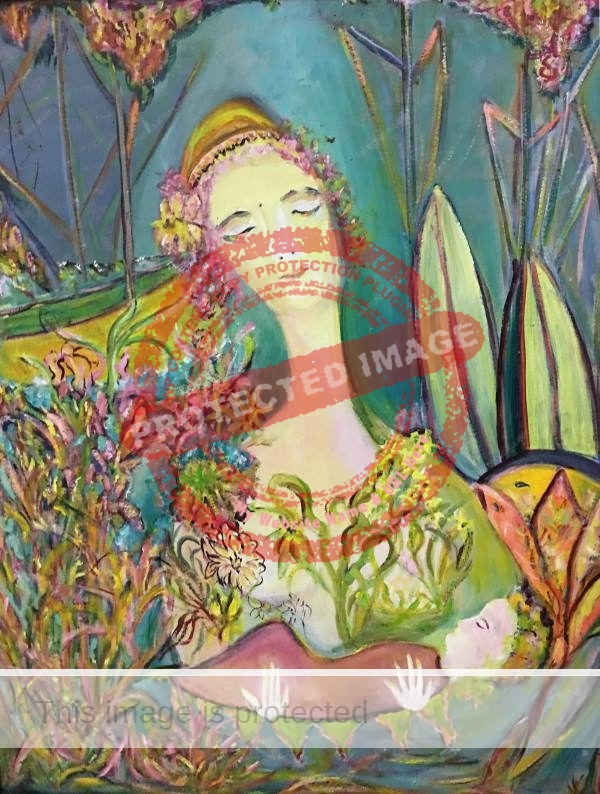

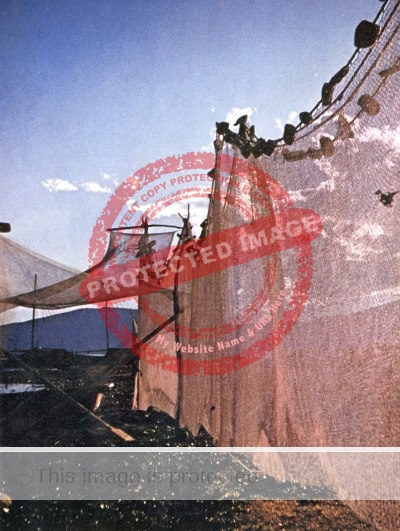

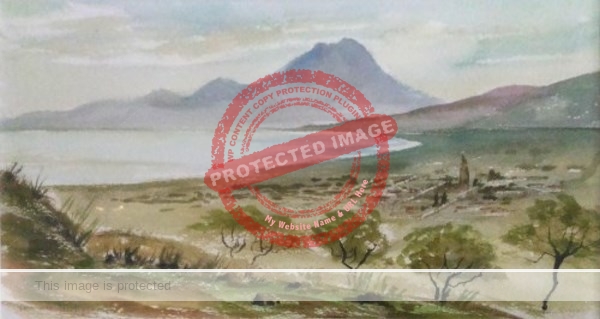

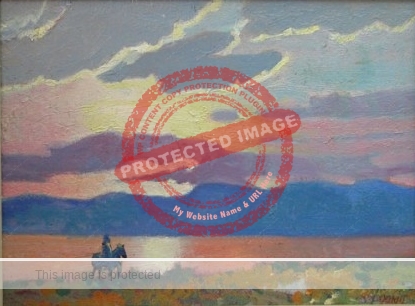

Roy MacNicol: Mood, Mexico (1936)

Roy MacNicol was a prolific painter and numerous MacNicol paintings of Lake Chapala are known. Romantically and artistically, he lived an especially colorful life and was involved in several high profile scandals and lawsuits.

Born in New York City on 27 November 1889, his mother was Spanish-Scandinavian (her father was Gustav Gerle, a noted Swedish artist who had graduated from the Royal Academy) and a Scottish military man, who died when MacNicol was an infant. His mother remarried and moved to Urbana, Illinois.

Partly on account of an abusive stepfather, MacNicol left home as a teenager. After taking night classes at the Paul Gearson Dramatic School, MacNicol took traveling repertory roles with the William Owen Company, before joining the Edna May Spooner Company in New York.

MacNicol married fellow cast member Mildred Barker (“Connie” in his autobiography) in 1914; their son Roy Vincent Jr. was born the following year in Michigan.

MacNicol continued his acting career and appeared in 1919 at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C., in the farces Twin Beds and Where’s Your Wife? on Broadway at the Punch and Judy Theatre.

At the time of the 1920 US Census, the family was apparently still living together in New York. However, Mildred then left, taking Roy Jr. with her, to move in with another man, while MacNicol fell in love with, and married (later that same year) vaudeville singer and performer Fay Courtney. MacNicol composed several original songs, such as “Indian Night” for his wife’s shows.

Tragically, Roy Jr. died at the age of 5 of diphtheria in Pennsylvania (not Ohio as MacNicol claims in his autobiography) in January 1921.

With the full backing of his new wife, MacNicol left the stage behind him and began to concentrate on his painting. Best known for his watercolors and elaborate decorative screens, MacNicol’s work embraced a number of different styles over the years before he developed (in the 1940s) a unique style he termed “geo-segmatic.” Many of his geo-segmatic paintings are justly prized.

MacNicol’s first solo exhibit was in November 1921 at the Anderson Galleries, New York. His bird and animal motifs on large screens were admired on opening night by more than 800 guests. This style led to a serious professional clash with a fellow artist, Robert W. Chanler. MacNicol was outraged when Chanler called him a “copyist” who had stolen his designs and took Chanler to court, asking $50,000 for the alleged libel.

His second solo show was in Palm Beach, Florida, by invitation of a wealthy patron. This was the start of the artist’s long connection with the Palm Beach area.

After visiting France and Spain in 1925-26, MacNicol held a solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in April 1926. Entitled “Recent Works of Roy MacNicol,” it included many abstract paintings of fauna such as cranes, herons, Australian squirrels and penguins. In the program notes, A. G. Warshawsky praised the abstract compositions that “still hold a human and essentially humorous effect, which adds both to the charm and naiveté of the subject.”

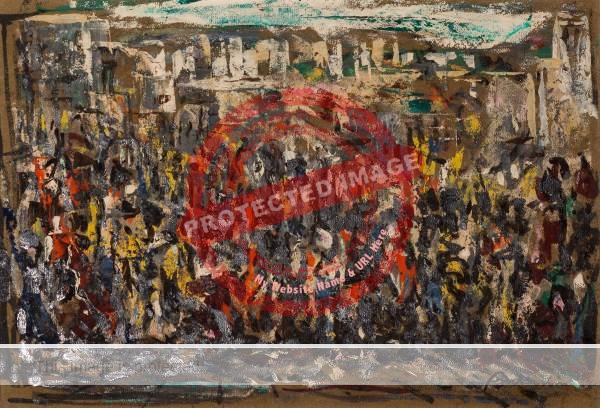

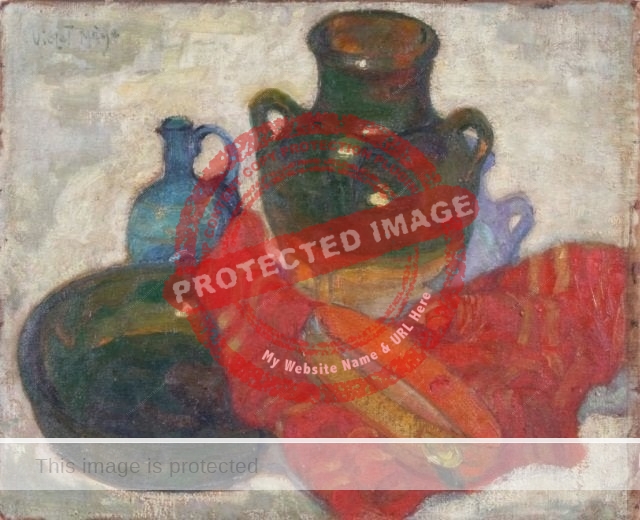

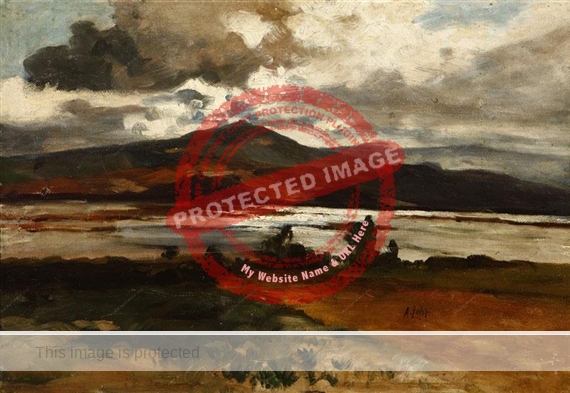

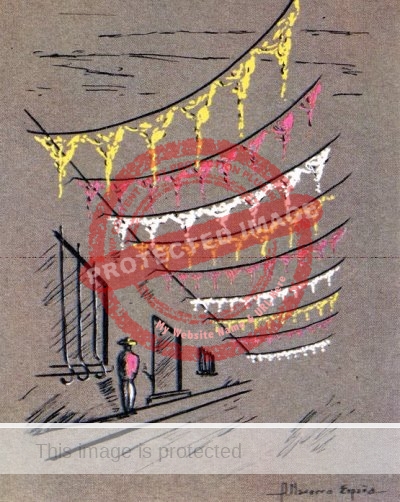

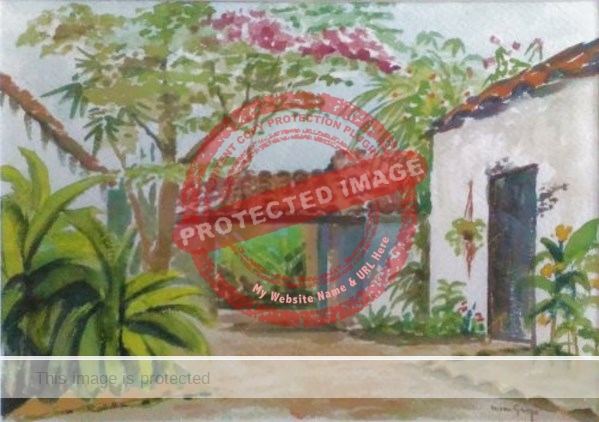

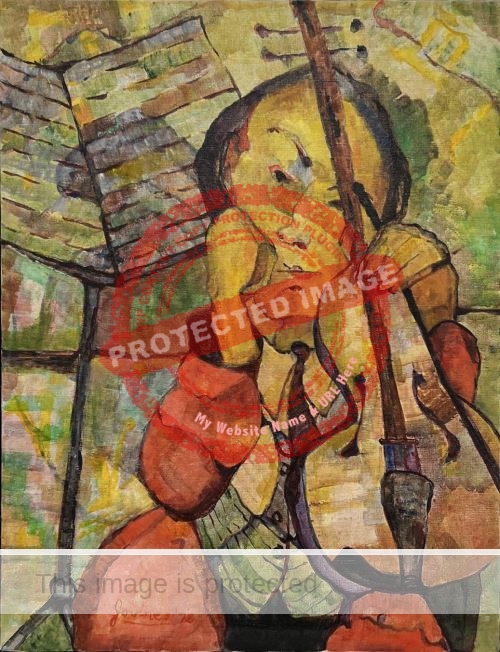

Roy MacNicol: Untitled (1961)

His wife’s singing career took the couple to London, England, and Berlin, Germany during the Great Depression, and to China and Japan for eight months over the winter of 1933-34.

Between these trips MacNicol held many more solo shows, including one at the Everglades Club in Palm Beach (1931)—MacNicol later opened (briefly) his own Salon of Fine Arts in that community in 1933— and at the A Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago (1933–34).

In about 1937, the MacNicols, on an impulse, decided to drive down to Mexico to seek more of the “Spanish flavor” that had inspired some of MacNicol’s best work to date. Between bullfights and an earthquake, Fay gave a successful concert, and Thomas Gore, the owner-manager of the Hotel Geneve in the Zona Rosa, commissioned Roy to paint two murals for the dining room, in which the artist depicted Xochimico.

The couple were enjoying a cruise around the Caribbean and South America, with Fay performing, and Roy taking color motion pictures for a series entitled “Through the Eyes of an American Painter” when Fay was taken ill. Fay Courtney MacNicol died in New York in February 1941.

Despite the heartbreak, MacNicol continued to paint, and, in October 1941 took a large “world collection of watercolors,” which had previously been shown in New York, Long Island and Trinidad, to Cuba, where the press dubbed him the “Good-will Ambassador,” a moniker which stuck.

On his return to the U.S., MacNicol revisited his old home town and donated eleven of his paintings to the university in Urbana, where he had once worked as an office boy. When he learned, years later, that they had never been put on display, he asked for them back.

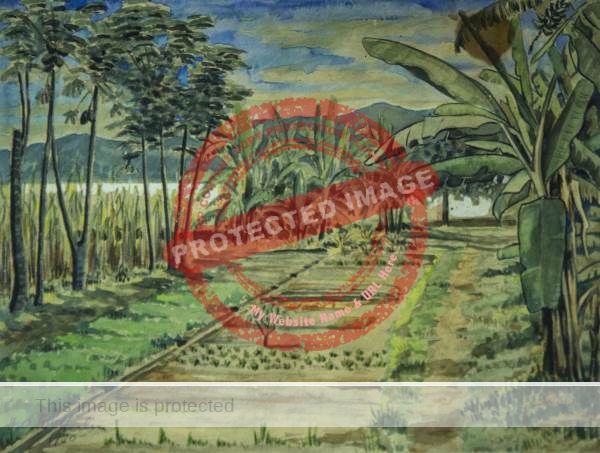

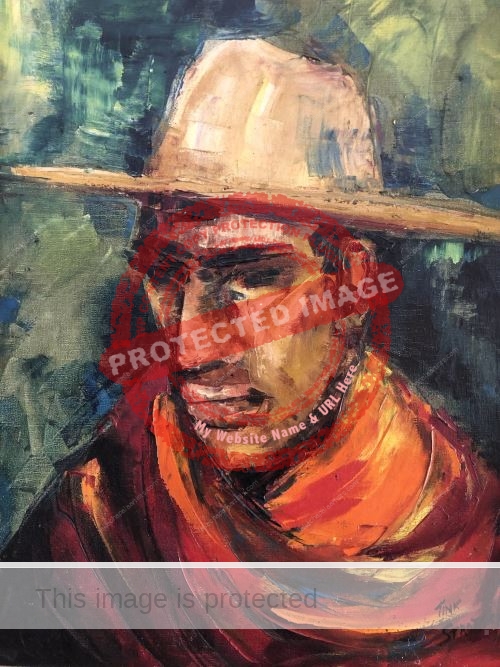

His frequent travels had given MacNicol the inspiration to compile a “good-neighbor” show of Mexican-inspired works as a means of improving the ties between Mexico and the U.S. MacNicol took a studio on Rio Elba in Mexico City and devoted nine months to painting a series of large (22 x 30″) watercolors. These were the basis of the “Good Neighbor Exhibit” that was subsequently shown in galleries across Mexico and the U.S. and received coast-to-coast television coverage.

MacNicol was dismissive of critics who argues his work was influenced by Diego Rivera, though he admitted that perhaps he had been influenced by the “entire Mexican school of art.” In particular, he admired the work of Siqueiros and of Rufino Tamayo, “the most charming, imaginative, and amusing painter in Mexico.”

The artist’s 33rd solo show opened on 4 March 1943 at the Pan American Union in Washington, D.C. It was greatly appreciated by Eleanor Roosevelt, who eagerly recommended the show:

“On leaving the club, I went to the Pan American Building to see an exhibition of paintings done in Mexico by Mr. Roy MacNicol. They were perfectly charming, and I was particularly interested in the Indian types. Some showed the hardships of the life they and their forefathers had lived. Others had a gentleness and sweetness which seemed to draw you to them through the canvas. The color in every picture was fascinating and I feel sure that this is the predominant note in Mexico which attracts everyone in this country who goes there.” (Eleanor Roosevelt, 5 March 1943)

The show then moved to venues in Chicago and Detroit. Mrs. Roosevelt sponsored some subsequent “Good Neighbor” exhibits, as did several prominent Mexican officials, including Mexican president Miguel Alemán.

MacNicol divided his time over the next few years between Mexico and the U.S. In October 1943, he exhibited more than 20 paintings in a solo show at the Galería de Arte Decoración in Mexico City. The titles of the works included references to Xochimilco, Jacala, Tamazunchale, Veracruz, Pátzcuaro and Amecameca.

Then, after a successful solo show in Los Angeles, he opened a “Good Neighbor” exhibit of 22 paintings in April 1945 in the Foyer of the Fine Arts Palace (Palacio de Bellas Artes), also in Mexico City. In MacNicol’s own words, “It is considered one of the greatest honors in the world for a painter to be invited to exhibit there.” The sponsorship of this show by the Mexican government led to great consternation and protests in local art circles who could not understand why their government would sponsor a foreign painter.

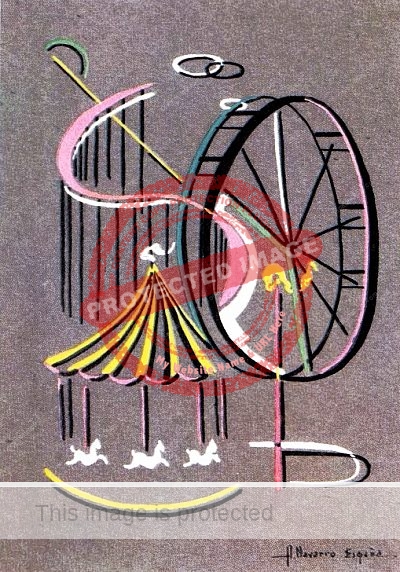

Roy MacNicol: Untitled (1961)

A few months later, back in the U.S. for shows in Oklahoma and Urbana, MacNicol had what he entitles in his autobiography “My great folly.” On 9 September 1945, he married Mrs. Helen Stevick, the “wealthy publisher of the Champaign, Illinois, News Gazette” in Chicago. MacNicol claims he had known the attractive widow for some time, didn’t love her, but wanted to “settle down.” Newly-married, the couple went to Mexico City for their honeymoon, where Stevick’s daughter – a 34-year-old “ravenous widow on a manhunt,” who wanted MacNicol to find her a new husband – joined them.

MacNicol’s marriage to Helen Stevick quickly became a complete disaster, leading to ample fodder for the newspapers of the time, who had a field day describing the plight (and possible motives) of the prominent painter. The Steviks accused MacNicol of fraud and had him (briefly) imprisoned in a Mexican jail. In retaliation, MacNicol sued the daughter for $500,000 for her part in wrecking his marriage.

Irving Johnson, for the San Antonio Light, wrote that:

“Roy V. MacNicol is a painter of Mexican scenes. The critics praise his work. Prominent Americans and the Mexican cabinet have sponsored his exhibitions. He has been called America’s paintbrush ambassador.

Now he’s laid down his brush temporarily to picture another kind of Mexican scene – his own unhappy honeymoon south of the border. His price is a half million – the amount of his recent alienation of affections suit against his own stepdaughter…”

MacNicol may have wanted $500,000, but he certainly did not get it; the case was dismissed on technical grounds. According to the divorce case the following May (1946), Mrs. MacNicol agreed with her daughter that he had married her only to get “large sums of money for his personal aggrandizement and the satisfaction of his idea of grandeur.” Ironically, that very month, Roy MacNicol held a successful show of Mexican watercolors in Chicago. The divorce was finalized on 29 July 1946.

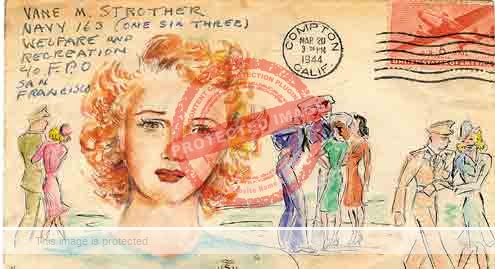

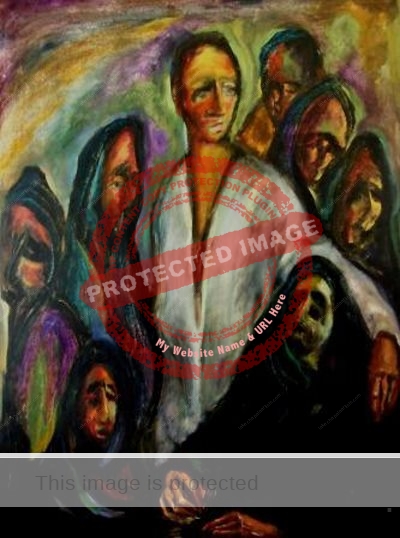

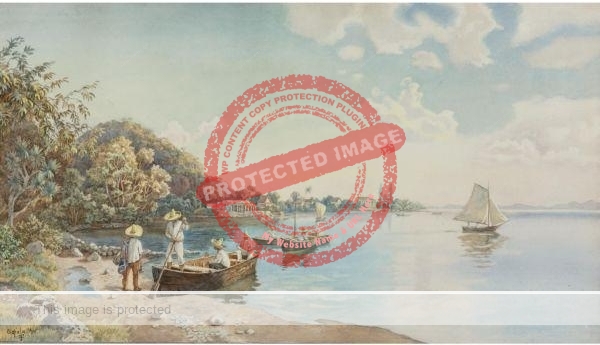

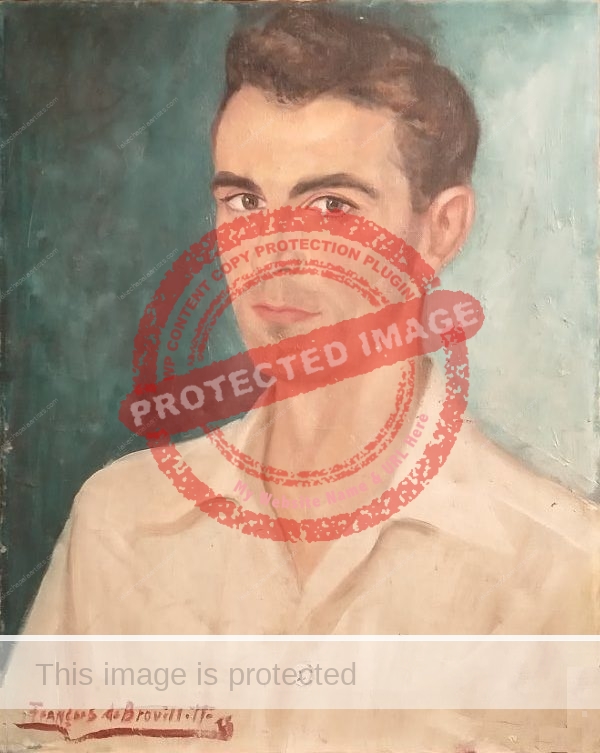

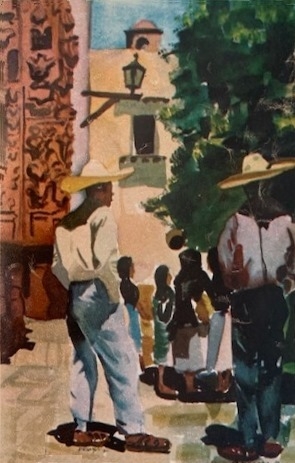

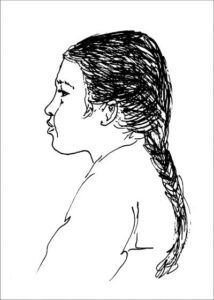

Roy MacNicol. The Lily Vendor. c. 1946.

MacNicol celebrated by heading for Sweden in September for a few weeks to explore his family roots and show his Good Neighbor exhibit at the AETA gallery.

Returning from Sweden, MacNicol decided to revisit Palm Beach for the first time in 15 years, and made arrangements to hold his 50th solo show there in the State Suite of the Biltmore Hotel. When Mrs Bassett Mitchell (the former Mary Blanche Starr) walked in the room he was instantly smitten. It turned out that Mary was the widow of a Florida financier and was equally enthralled. She bought “The Lily Vendor”—“a dark-skinned Mexican girl selling sheafs of white lilies in a glow of sunlight”—and then they had dinner together. (The painting was later used for the cover of Mexican Life magazine.) Within weeks they announced their engagement and they married at her home in Palm Beach on 27 March 1947, before spending their honeymoon in Nassau. Their love for each other never diminished.

Later in 1947, a trip to Jamaica and Haiti proved to be the source of inspiration for MacNicol to devise what he terms his “geo-segmatic” style of painting. The first major exhibition of these works was held in Paris, France, (solo show number 53) in May 1948, where he met the famous Mexican singer and actor Jorge Negrete.

The following year, after a successful show at Penthouse Galleries in New York City, the MacNicols decided to move from Palm Beach to Mexico City. They drove down there in their Lincoln convertible (with four truck loads of furniture following behind) and bought a 3,000-square-meter property in Coyoacan. They spent the next two years adapting it into a house, studio and gallery.

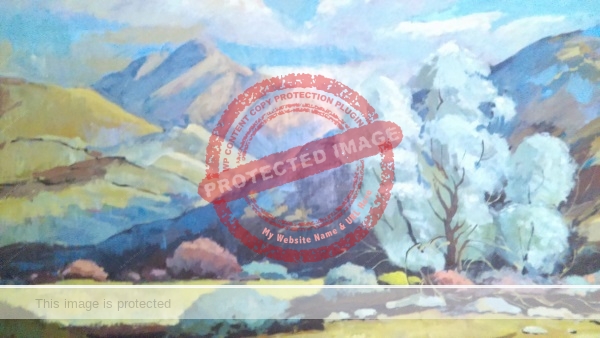

Health issues led them to sell their Mexico City home and start driving around Mexico in search of a new home at a lower elevation:

“We took three months motoring around before we discovered the enchanting little fishing village of Chapala, tucked on the banks of a sparkling lake, set among emerald mountains and violet haze. There was a blessed tranquillity in the low rooftops and the plaza overshadowed by giant laurel trees. But it also had the advantage of a modem four-lane highway leading through rolling green hills from Guadalajara, the second largest, and the cleanest, city in Mexico, a drive of only thirty-five minutes. (Paintbrush Ambassador, 226-7)

They drove into Chapala in January 1954 and, within days, bought a property that MacNicol later claimed hadn’t been lived in for a decade – the very same house, at Zaragoza #307, which British novelist D. H. Lawrence had rented in 1923.

The MacNicols restored the house and added a swimming pool. They also added a memorial plaque on the street wall to Lawrence: “In this house D. H. Lawrence lived and wrote ‘The Plumed Serpent’ in the year 1923.” A second wall plaque had a quote from another of MacNicol’s boyhood heroes, Robert Louis Stevenson.

– “That man is a success who has lived well, laughed often and loved much. Who has gained the respect of intelligent men and the love of children. Who has filled his niche and accomplished his task. Who leaves the world better than he found it, whether by an improved poppy, a perfect poem or a rescued soul. Who never lacked appreciation of earth’s beauty or failed to express it. Who looked for the best in others and gave the best he had.”

A “list of foreign residents in Chapala” from June 1955, and now in the archive of the Lake Chapala Society (LCS), includes Roy and Mary MacNicol among the 55 total foreign residents in the town at that time, though they were not LCS members. According to MacNicol, “Chapala has its retired American naval and military brass, business men, delightful English, some good writers and myself as the only painter.”

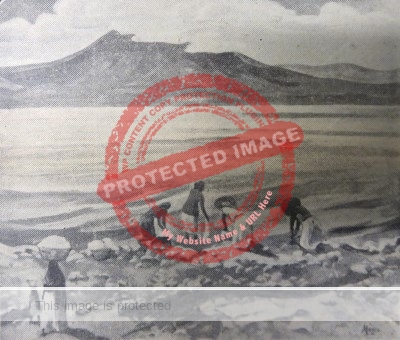

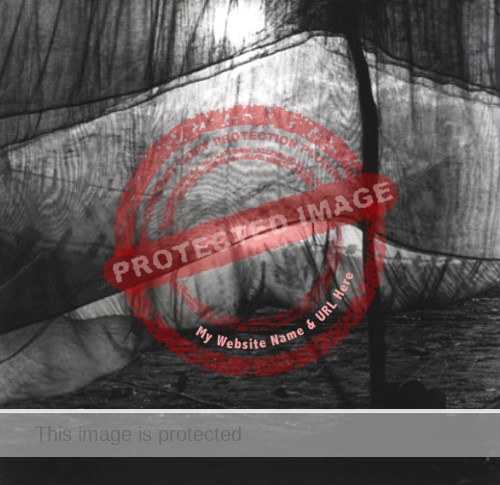

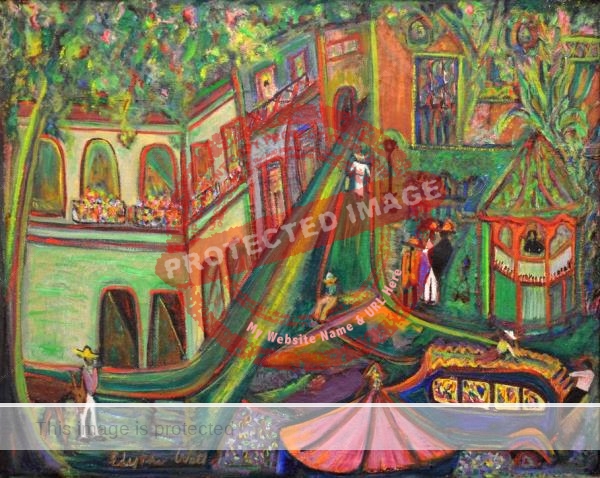

Roy MacNicol. 1956. Poolroom, Chapala, Mexico. B/W photo of oil in tones of red and green. (Plate 11 of Paintbrush Ambassador)

In 1956, MacNicol was persuaded to hold an exhibit in Copenhagen, Denmark. He and Mary flew from Mexico City to New York, carrying 52 paintings and then sailed on the MS Kungsholm across the Atlantic. The show was an unmitigated disaster, largely owing (according to MacNicol) to the complete absence of any help or support from the local U.S. Embassy. The MacNicols returned home to Chapala in November.

It is unclear precisely when the MacNicols sold their house in Chapala, but according to columnist Kenneth McCaleb, MacNicol was disposing of the contents of his Chapala home in the early 1960s, prior to selling it and moving to New York.

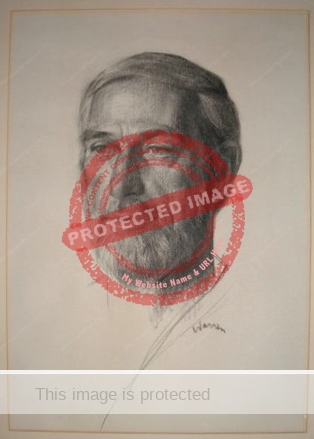

The exhibition catalog dating from late 1968 or early 1969 for MacNicol’s “Faces and Places of Nations” exhibit says it was the artist’s 59th (and last) solo exhibit. The catalog describes the “Paintbrush Ambassador of Goodwill”:

“He believes in the universal diplomacy of art as a means to world understanding. His “Faces and Places of Nations” series was begun in 1943. The exhibit has been shown in Mexico City, Spain, Paris, Stockholm, Copenhagen, British West Indies, Cuba, South America, as well as in key cities in U.S.A. The 1949 exhibition was televised coast-to-coast by NBC.”

Of the sixteen works listed in the catalog, six are from Mexico, including two directly linked to Lake Chapala: “Old Fisherman & Boy (Lake Chapala)” and “Mary & Duke, Casa MacNicol (Lake Chapala).” Duke was MacNicol’s Dalmation.

In addition to painting, MacNicol frequently lectured on art and his formal jobs as a young man included a spell as associate editor at the American Historical Company in New York City. He was a contributor to several newspapers including the Christian Science Monitor, Atlanta Journal, The Times Herald, Mexico City News and The Havana Post.

His autobiography—Paintbrush Ambassador—mentions dozens of notable personalities including the likes of Ernest Hemingway, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jack Warner, Danny Kaye, Gloria Swanson and Mr. and Mrs. Nelson D. Rockefeller.

MacNicol died in New York in November 1970.

Examples of his artwork are in the permanent collections of the University of Illinois; Randolph-Macon Woman’s College; University of Havana, Cuba, and the Reporter’s Club, Havana.

Despite enjoying considerable success (and some notoriety) during his lifetime, Roy MacNicol is among the many larger-than-life artists to have lived and worked at Lake Chapala whose artistic contributions to the area’s cultural heritage have, sadly, been largely forgotten.

Sources

- Irving Johnson. 1946. “Honeymoon for Three.” San Antonio Light, 24 November 1946, 59.

- Roy MacNicol. 1957. Paintbrush Ambassador. New York: Vantage Press.

- Kenneth McCaleb. 1968. “Conversation Piece: How To Be an Art Collector,” The Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 15 February 1968, 17.

- New York Times, 26 May 1925.

- The Palm Beach Post, 20 March 1947.

- Eleanor Roosevelt. “My Day,” Kansas City Star, 5 March 1943, 23.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

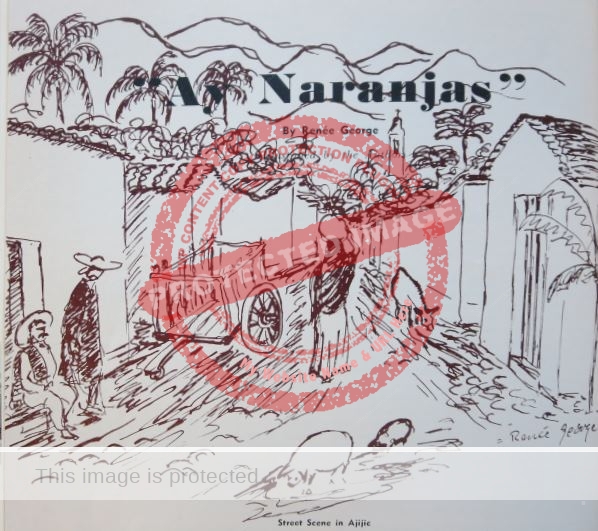

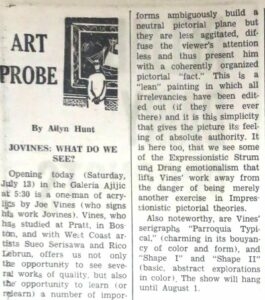

Joe Vines, sometimes mistakenly spelled as either Jo Vines or Joe Vine in contemporaneous news reports, was a male artist who signed his work “Jovines.” He held a solo show in March 1968 at the “Galería Ajijic Bellas Artes,” administered by Hudson and Mary Rose, that was located at Marcos Castellanos #15 (at the intersection with Constitución) in Ajijic. Reviewing the show, Allyn Hunt described his work as “sparkling, colorful silkscreen prints.”

Joe Vines, sometimes mistakenly spelled as either Jo Vines or Joe Vine in contemporaneous news reports, was a male artist who signed his work “Jovines.” He held a solo show in March 1968 at the “Galería Ajijic Bellas Artes,” administered by Hudson and Mary Rose, that was located at Marcos Castellanos #15 (at the intersection with Constitución) in Ajijic. Reviewing the show, Allyn Hunt described his work as “sparkling, colorful silkscreen prints.”