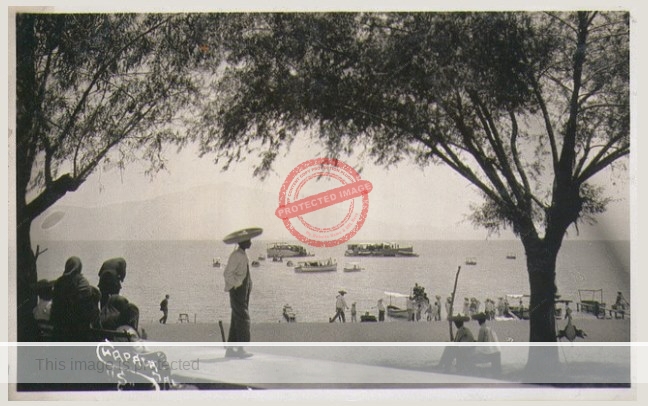

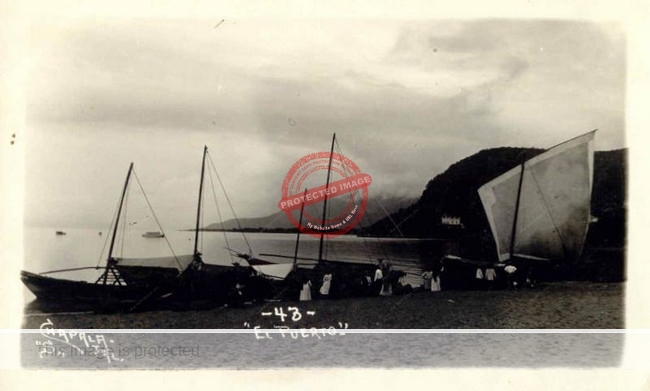

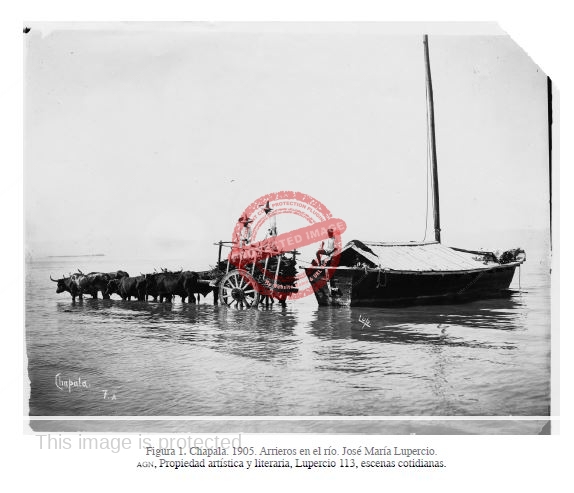

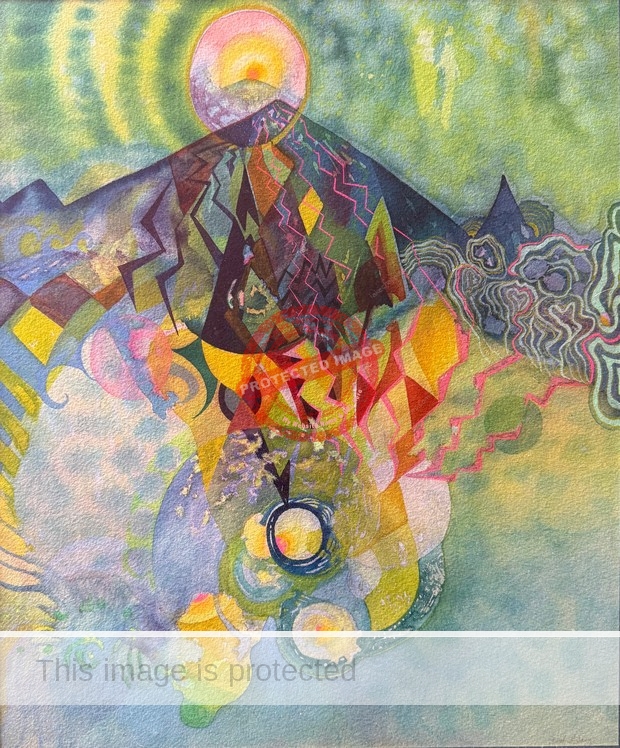

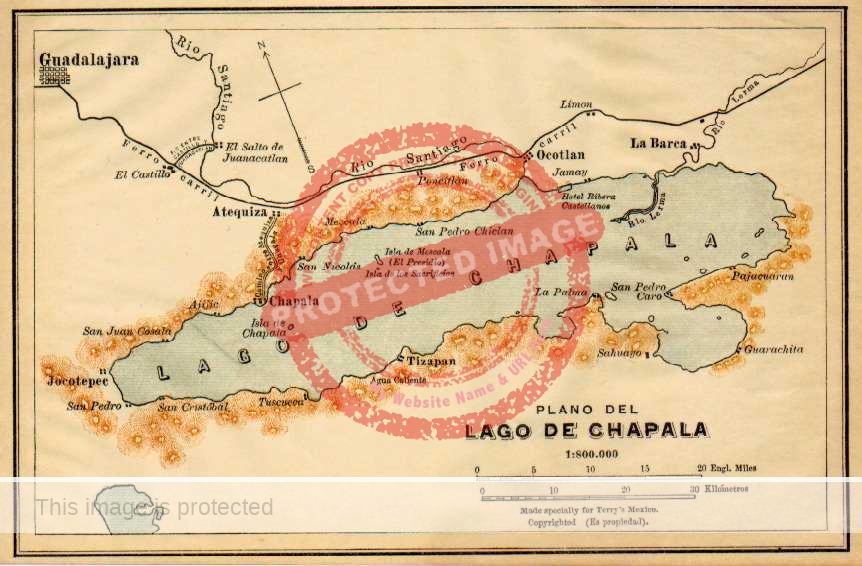

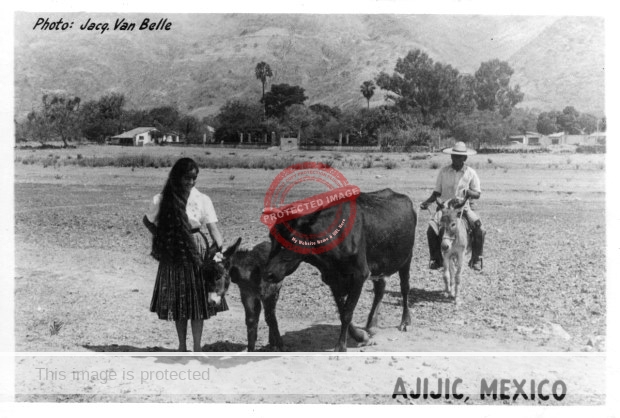

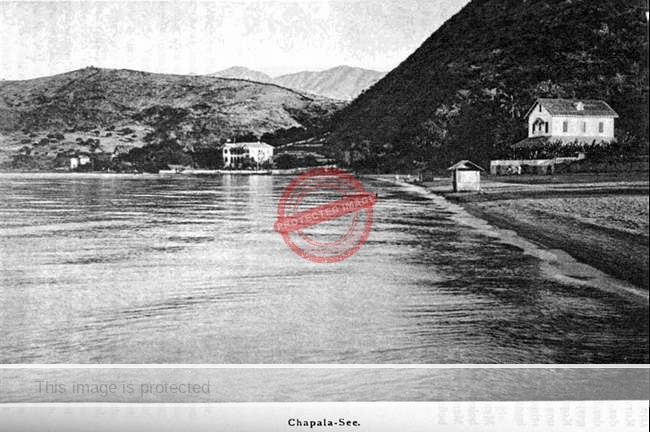

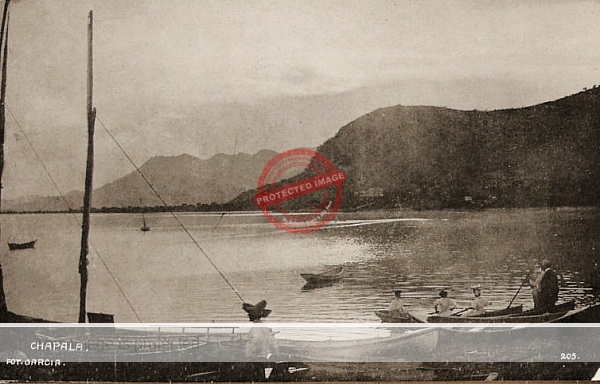

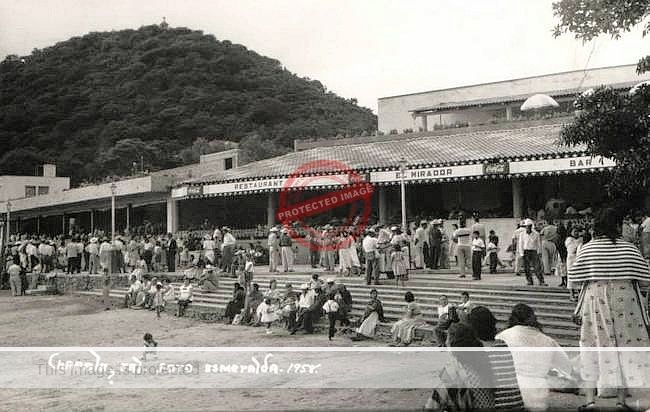

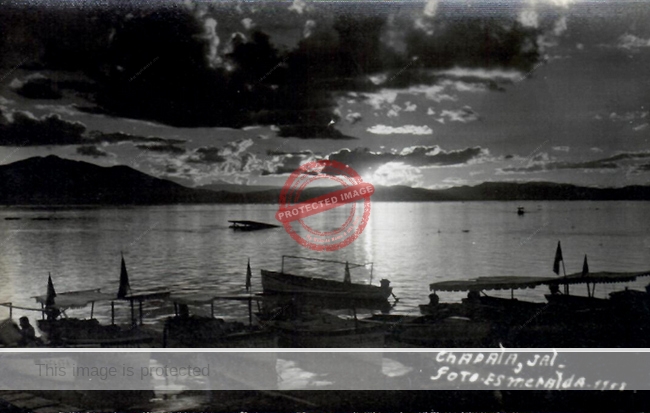

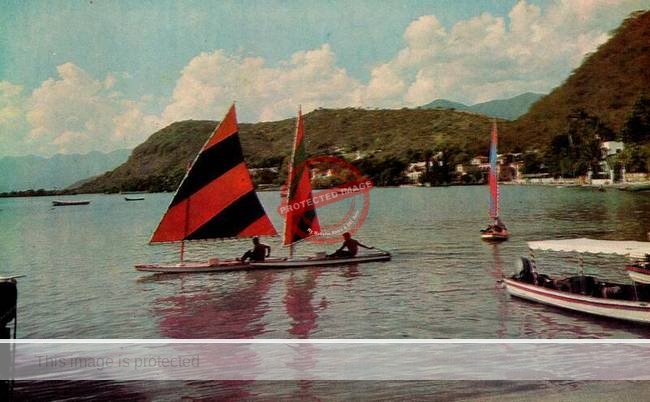

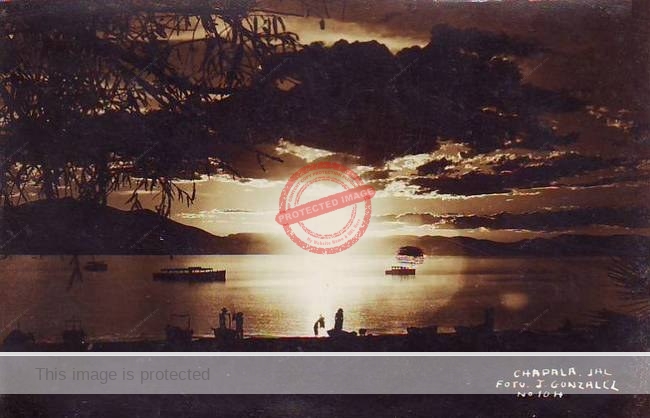

Among the early grayscale postcard photographs of Lake Chapala are several well-composed views signed L. V. García. In researching this photographer, I stumbled across an article which included this image of Lake Chapala, captioned “L. V. García. Alrededores de Guadalajara: Chapala, Jalisco. Ca. 1900,” held in the Fondo Fotográfico Antonio Alzate of the National University (UNAM).

L. V. García. Alrededores de Guadalajara: Chapala, Jalisco. (c 1900). Col: UNAM, IIH, Fondo Fotográfica Antonio Alzate.

This postcard is unusual, and quite avant-garde for its time. It may be slightly later than 1900, given that several other photos of Chapala by the same artist were definitely taken post-1904. But the strong composition, details, and novel way of embracing the lake in artistic flowers, make this card more of a work of art than any mere traveler’s memento.

Librado V. García, it turns out, was one of the most enigmatic Mexican photographers of all time. While virtually nothing is known about his personal life, he opened photo studios in both Mexico City and Guadalajara, and adopted the moniker “Smarth” as he moved away from conventional portraits and landscape images towards artistic photographs that helped lead a revolution in Mexican photography.

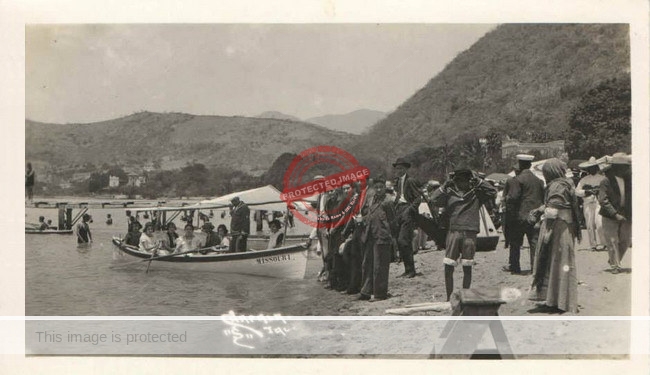

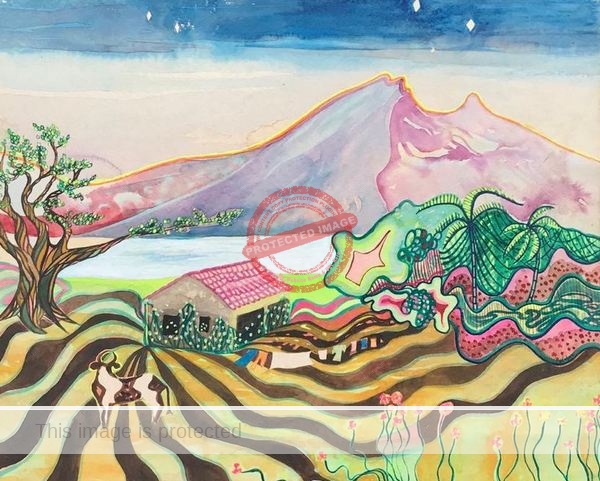

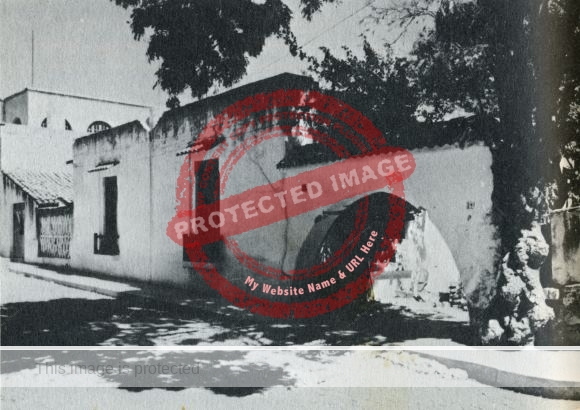

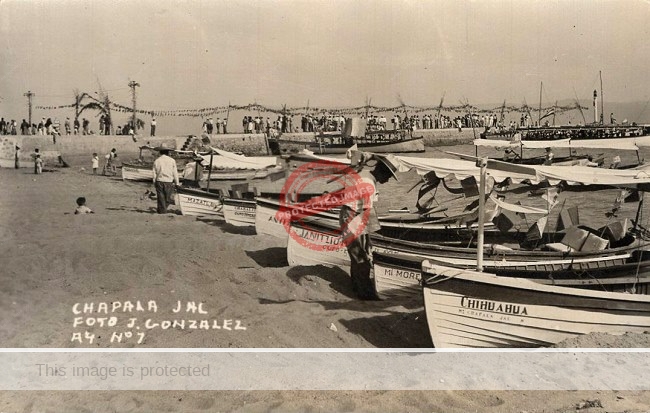

García was responsible not only for the artistic card above but for numerous conventional photographic postcards of Chapala, including two cards, one signed “L. V. García” and the other “FOT. GARCIA” which were taken from the jetty in Chapala and show the shoreline buildings east of the church. Closer inspection showed that the FOT. GARCIA version (which has the number 209 in tiny print at the bottom right) is an enlargement of one small section of the other version. These two cards were presumably published at different points in the photographer’s career. A third postcard, with the identical photo, is also known, though it lacks any credit, title or number on the front.

In addition, there are several “Edic. García” or simply “García” postcards that are clearly the work of the same photographer, especially since the way “García” is written—partially enclosed in a line that serves to underline the name—exactly matches how it appears on several “L. V. Garcia” cards.

Given that only about 200 photographs by Librado García “Smarth” are known, the addition of these postcards to his oeuvre may offer some clues as to when and how the artist gradually became a master of composition and technique.

L. V. García (Fot. García). Chapala (c 1900).

In an interview in the 1920s, García claimed to have been born in a cave in the mountains of either Sinaloa or Jalisco. According to art collector and researcher David Torrez, García was born in 1892 on the hacienda de la Cuesta, close to the Jalisco/Nayarit state limits.

In that same 1920s’ interview, García claimed that his birth was never registered, and so he had no idea of his real age or date of birth. He had chosen the name Librado García himself, and had worked as a telegrapher and for the postal service before being inspired to investigate photography after a friend took his portrait as a decapitated body holding his head in his right hand.

García bought a camera, read the manual, experimented and taught himself. If there are any grains of truth in this fabulous tale they presumably help to account for his artistic originality, perceived closeness to indigenous Mexico, and reputation for incorporating a strong sense of nationalism in his images.

This enigmatic photographer with his creative backstory presumably believed that his photographs should be judged squarely on their artistic merits and that opinions about them should not be influenced by any knowledge of the photographer’s personal background, education or life experiences.

According to Jaliscan artist and politician José Guadalupe Zuno, Smarth‘s career as a master portraitist began in 1911, a date supported by photography researcher José Antonio Rodríguez who traced Librado García’s career back to a listing for his photo studio (at Avenida Madero #66) in a 1911-12 Mexico City directory.

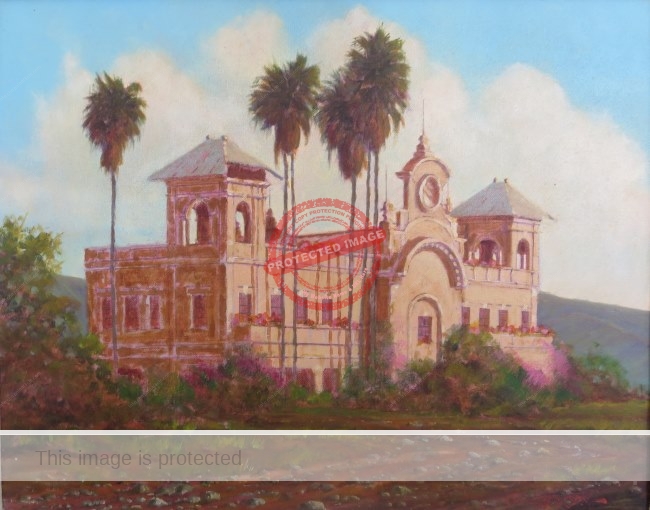

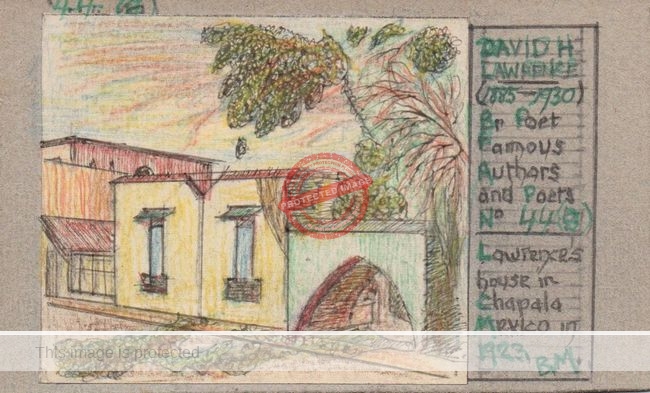

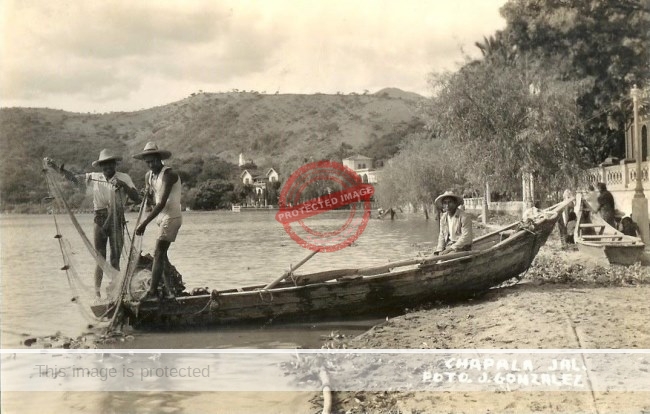

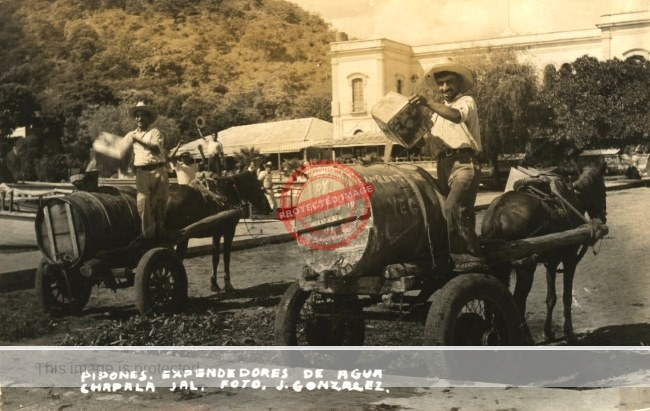

L. V. García. Alrededores de Guadalajara: Chapala, Jalisco. (c 1905).

The start of his career as an artistic photographer may date from 1911, but García was clearly active well before this, as proven by his postcard views of Lake Chapala, some of which were mailed prior to 1910. On the other hand, some of his photographs must be post-1904 since they show Casa Braniff (as it is popularly called), construction of which began that year.

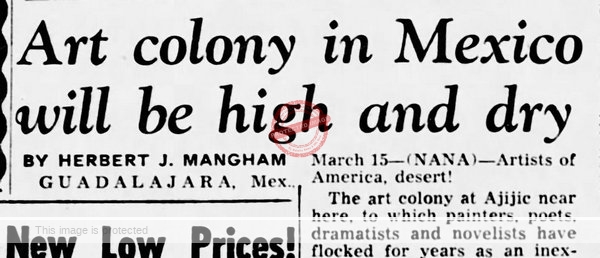

García was clearly already well-known in Guadalajara, and presumably had a studio there, several years before opening “Foto Smarth” at Avenida Corona #128 in Guadalajara in October 1915. During the next decade, Smarth was very active in Guadalajara. In 1918, and again in 1919, he advertised his search for “three apprentices without pretensions,” and regularly donated prizes to major local fund-raisers such as the raffle held for the Red Cross in February 1918.

Smarth was a fun-loving character with a reputation for throwing interesting parties. In February 1920 he organized a masked ball at his photo studio in Guadalajara one evening for young ladies “wearing capricious dresses”, where the intent was to display originality and good taste. The following October, he sent out invitations for a new exhibition of photographic works. The local paper was certain that the show would gain the artist new admirers.

Smarth’s photographs were included in a group exhibition of local artists at the Guadalajara Male Teachers’ School (Escuela Normal para Varones) in September 1921.

In August 1922, El Informador reported that “Sr Librado García, Smarth” had just returned to the city from a few days’ vacation in Cuernavaca. Two days later, there were references in the paper to a “Sra de Smarth” and “Srtas Smarth”, suggesting either that Librado Garcia had a wife and daughters, or an unlikely coincidence of names.

The following March, Sr and Sra Smarth are named on a lengthy list of those present at the official inauguration of the railroad from La Quemada (near Magdalena) to Tepic. This was a major event. President Álvaro Obregón did the honors, accompanied by his eventual successor Plutarco Elías Calles, and dozens of high-level politicians, railway officials, guests and members of the international press. One Chapala-related curiosity about this list is the inclusion of Miss Helen Creighton, a Canadian author and folklorist who was employed as a teacher at the American School in Guadalajara and took several snapshots of Chapala that year.

From 1924 to 1926, Librado Garcia taught photography workshops in Guadalajara at the Young Women’s Industrial School (Escuela Federal de Arte Industrial para Señoritas), a school established to promote economic independence for young women. In December 1924, the school celebrated its first year with a seasonal fiesta and exhibitions showcasing student work in fields ranging from sombrero-making, fashion design and embroidery to decorative art, bookbinding, drawing and photography.

Smarth‘s classes were especially popular. A display of student photography in November 1925 “showed the notable progress made by students, and accounted for the large number of students taking the course.” The numerous enlargements and photos taken by students of each other and their teachers were praised as especially artistic, demonstrating a mastery of the use of light to obtain images with varying tonalities.

For some years, the photographer apparently maintained studios in both Guadalajara and Mexico City simultaneously before deciding to close the Guadalajara studio to focus exclusively on work in the capital.

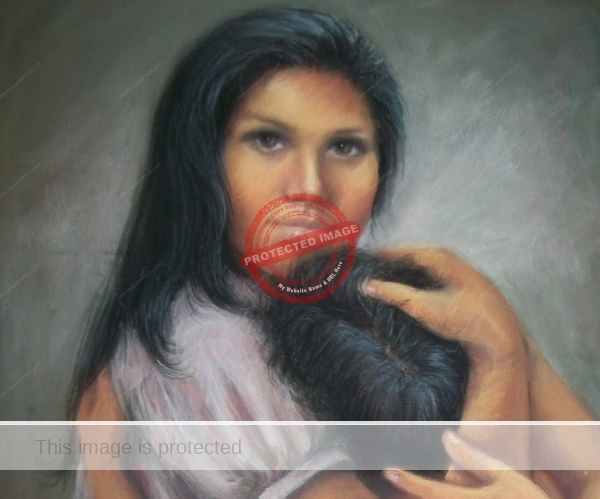

By the early 1920s, Smarth‘s portraits had matured into true works of art, characterized by strong composition and the use of settings or backdrops often drawn or painted by the photographer himself for the specific individual. Smarth was among the first to hold portrait sessions where he would choose the attire of his sitters and experiment with a variety of poses and backgrounds. Smarth took striking portraits of many notable figures of the time including the American ballerina Rosa Rolanda. Rolanda, the wife of Miguel Covarrubias, not only sat for painters Diego Rivera and Roberto Montenegro but also posed for photographers Edward Weston and Tina Modotti.

Photos by Smarth appeared in many of the leading papers and magazines of the time, including El Universal Ilustrado, Revista de Revistas, Jueves de Excélsior and Cúspide in Mexico City and El Informador in Guadalajara.

From about 1926, García chose to live primarily in Mexico City, making occasional trips back to Guadalajara. For example, he is recorded as leaving Guadalajara at the end of March 1929 on the night train to return to Mexico City “where he has lived for some time”.

Smarth, described as a photographer with “imagination and elegance,” was a prize-winner at the 1929 Expo Seville (Feria Iberoamericana) in Spain, as were his Mexican colleagues Antonio Garduño, Hugo Brehme, Roberto A. Turnbull, Ignacio Gómez Gallardo and Tina Modotti.

It was also in 1929 when Mexico’s first monthly national photo magazine was launched. The inaugural issue of Helios, Revista Mensual Fotografica announced the creation of an Asociación de Fotógrafos de México (with Macario González as president) and invited readers to participate in photographic contests. Helios ran until 1936, and competition winners included several Guadalajara photographers—Librado García, Ignacio Gomez Gallardo and Eva Mendiola—as well as Tina Modotti and Eva González.

A major collective exhibit of works by Mexican photographers was held in December 1929. This show, titled “Guillermo Toussaint y 11 fotógrafos mexicanos”, took place in the Galería de Arte Mexicano, located in what was then Mexico City’s Teatro Nacional (now the Palacio de Bellas Artes). Carlos Mérida and Carlos Orozco Romero, the organizers, invited 11 photographers—Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Hugo Brehme, Rafael García, Librado García Smart, Agustín Jiménez, Ricardo Mantel, Luis Márquez, Juan Ocón, Roberto Turnbull, Aurora Eugenia Latapi and Aurora Latapí (her mother)—to show their work, alongside sculptures by Guillermo Toussaint.

According to Cynthia Pérez, Smarth‘s activity as a photographer ceased in about 1936. He dropped out of sight in the 1930s; his life has been little researched and his work is little known.

The stunning black and white photos taken by these talented photographers were the forerunners for the marvelous cinematography of movies filmed in Mexico in the 1930s, movies that heralded the golden age of Mexican cinema.

Over the years, Smarth and his work soon became largely forgotten, though one significant group show in 1953 did include several of his fine photographs. This was a collective exhibit organized by the University of Guadalajara at the “Galeria de Art Contemporáneo” in downtown Guadalajara. Titled “Plástica Jalisciense (1668-1953)”, it included photographs taken by Smarth, José María Lupercio, Ignacio Gómez Gallardo, Lola Álvarez Bravo and Juan Victor Aráuz, as well as sculptures by Miguel Miramontes and innumerable paintings.

Lingering memories of Smarth lived on in Guadalajara. Columnists in El Informador periodically bemoaned the fact that the work of the city’s talented photographers, especially Librado García “Smarth,” Ignacio Gómez Gallardo, José María Lupercio and Pedro Magallanes had been forgotten. One lament, by Dr. Pedro Rodríguez Lomelí, came in a general piece headlined “Decline of Art in Jalisco.” Decades later, in the 1960s, one journalist claimed that the reasons why their fine work had been forgotten were “time, ingratitude and ignorance.”

Fortunately, Smarth’s artistic reputation has been more than restored in recent years, and he is now widely recognized as one of the earliest artistic photographers in Mexico. This re-evaluation coincided with a 2008 exhibit at the Museo de Estanquillo (Colecciones Carlos Monsiváis) in Mexico City, which included three unattributed nudes of Jaliscan painter Chucho Reyes Ferreira. Art researcher Carlos Córdova identified them as the work of Smarth and showed that they belonged to a series of unsigned portraits of Reyes, some of which had originally been published in 1920. Examples of the photographs were then included in a traveling exhibit about the development of portraiture titled “Te pareces tanto a mí” shown in Oaxaca, Mexico City, Guadalajara and Puebla in 2010. Carlos A. Códova’s research into Smarth and other early photographers won him the National Photography Essay Prize in 2010 and was published in 2012 as Tríptico de sombras.

By then, another researcher, José Antonio Rodríguez had shown that Smarth was responsible for several photos previously attributed to other famous photographers, including an image of a single alcatraz (calla lily), previously displayed as the work of Edward Weston.

In 2016 there was widespread press coverage when the Patricia Conde Galería in Mexico City assembled a small but powerful exhibition of 20 photographs titled “Smarth: Obras maestras de Librado García, fotógrafo.” A second major exhibit of his works titled “Librado García Smarth: entre el pictoralismo y la vanguardia,” opened 1 July 2021 at Casa ITESO Clavijero in Guadalajara.

The idea that “modern” Mexican photography really got underway only after the arrival of outsiders, such as Tina Modotti and Edward Weston in 1923, needs serious revision. By then, an artistic revolution in Mexican photography was already well underway, led by Smarth and others.

Smarth’s early postcards of Lake Chapala were the starting point for a truly memorable artistic journey, one that helped change the face of Mexican photography and still resonates with art lovers today.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

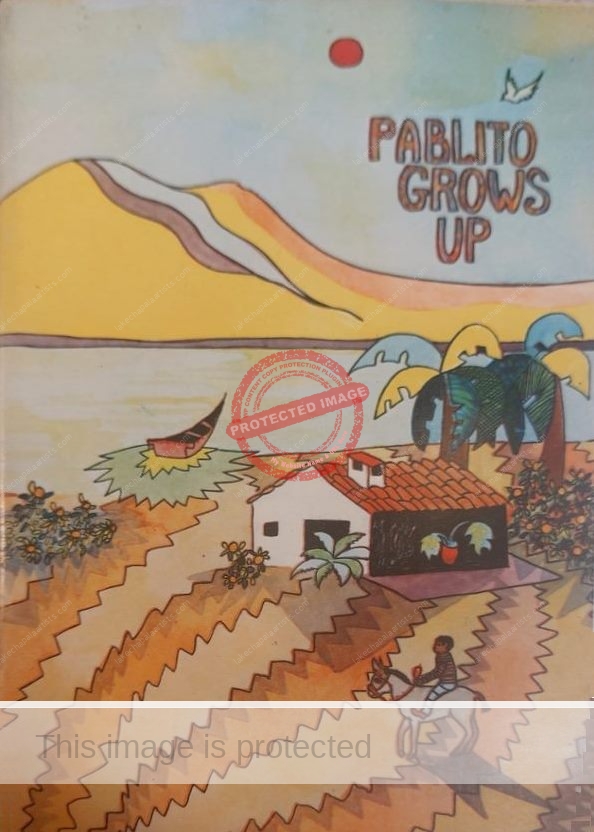

My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources:

- Carlos A. Códova. 2012. Tríptico de sombras. Mexico City: Conaculta/Cenart/Centro de la Imagén.

- Francisco Javier Ibarra. 2005. “Pioneras de la fotografía en Jalisco.” El Informador: 06 March 2005, 30.

- El Informador: 3 February 1918, 4; 3 February 1918, 3; 3 September 1919, 4; 17 Feb 1920, 8; 6 Oct 1920, 7; 25 Sep 1921, 5; 23 Aug 1922, 7; 25 August 1922, 7; 6 March 1923, 1, 8; 1 December 1924, 5; 22 November 1925, 8; 1 April 1929, 4; 3 October 1965, 27; 23 October 1966, 25.

- Arturo Jiménez. 2010. “Fotografías con desnudos de Chucho Reyes y Nahui Ollin dialogarán en Guadalajara.” La Jornada, 8 Sep 2010, 8.

- Cynthia Pérez. 2016. “El Misterio Detrás de un visionario, Librado García Smart.” Cuartoscuro. July 2016.

- José Antonio Rodríguez. 2011. “Librado García Smart: cortejar a la sombra.” Alquimía. Vol 14, No 41 (Jan-April 2011), 20-36.

- Pedro Rodriguez Lomeli. 1939. “Decaimiento del Arte en Jalisco”. El Informador, 4 June 1939, 11, 12.

- Cecilia Vilches Malagón and Martín Romero Sandoval Cortés. 2016. “La tarjeta postal como fuente de información para entender la historia de un país“, in Imatge i Recerca: Jornades Antoni Varés (14es: 2016: Girona) Tribuna d’Experiències – 2016.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcomed, whether via the comments feature or email.

Nina was born on 19 September 1921 in Taastrup, Denmark, and became a U.S. citizen in 1958 while living in New York City at 248 E. 50th St., where she worked as a hair stylist for the Charles of the Ritz Salon. When she moved to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1950, her new employer—Gould’s Kimbrough Beaty Salon in Kimbrough Towers—advertised that Ketmer had studied with the famous stylist, Rene-Rambau, in Paris” and arrived in the U.S. after “fifteen years of experience in the finest European Salons… in Stockholm and Copenhagen, Denmark and in Paris.” Given that she was still only about thirty years old when she moved to Memphis, this promotional blurb must be somewhat exaggerated. It is unknown how, where or when she acquired her sculpting skills.

Nina was born on 19 September 1921 in Taastrup, Denmark, and became a U.S. citizen in 1958 while living in New York City at 248 E. 50th St., where she worked as a hair stylist for the Charles of the Ritz Salon. When she moved to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1950, her new employer—Gould’s Kimbrough Beaty Salon in Kimbrough Towers—advertised that Ketmer had studied with the famous stylist, Rene-Rambau, in Paris” and arrived in the U.S. after “fifteen years of experience in the finest European Salons… in Stockholm and Copenhagen, Denmark and in Paris.” Given that she was still only about thirty years old when she moved to Memphis, this promotional blurb must be somewhat exaggerated. It is unknown how, where or when she acquired her sculpting skills.

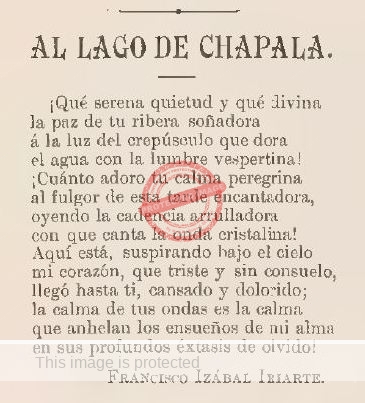

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

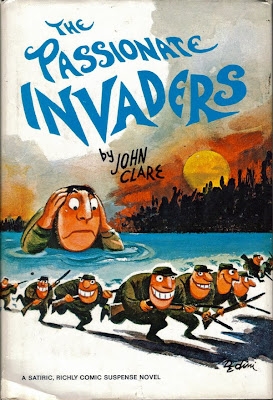

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’